States are slow to adopt controversial new science standards

All but five states have signed on to the Common Core State Standards in math and English, but states have been more tentative about picking up new science standards released in April. Known as the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS), the new guidelines, which call for a greater emphasis on problem solving than previous standards and teaching of core ideas that cut across physics, biology and chemistry, such as proportionality and cause and effect, are generating as much controversy as their sister standards.

The standards were developed by a consortium of 26 states that have committed to giving serious consideration into their adoption. But so far just five states, including Maryland, Vermont, Rhode Island, Kansas and Kentucky have adopted the NGSS.

Officials in Kentucky faced backlash over the inclusion of such topics as evolution and climate change in the standards (although evolution was included in Kentucky’s previous science standards). But aside from political reactions to the NGSS, the new guidelines are also facing objections from an academic standpoint.

Some opponents say the science standards are vague, stress scientific practices too much instead of covering more theory and that some states already have standards that are superior to the NGSS. Most notably, the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, a right-leaning education think tank, gave the standards a ‘C’ grade, a lower rating than grades it assigned to the current standards of 13 states.

Comparing NGSS to Washington, D.C.’s current standards, for instance, the Fordham study said the new science guidelines are subpar because they omit essential content, such as the topic of covalent bonding in high school chemistry, overemphasize engineering practices, like coming up with problems and models to solve them, and fail to integrate sufficient math into science learning.

The National Science Teachers Association, who support the science standards and had a hand in their development, strongly disagreed with the study. Executive director David L. Evans said in a statement that thousands of educators and experts were involved in the development of these new standards and an informal poll found 83 percent of those who responded believe they would have a positive impact.

“The NGSS is based on a current and robust body of research established by our nation’s leading scientists. In contrast, the Fordham review is based on personal opinions and lacks serious substantive research. We need to prepare students for the next generation, not the last,” he said.

Paul Bruno, a middle school science teacher from California – a state which got an ‘A’ in the Fordham ratings – has gotten attention for his critique of the NGSS. He said that basic content knowledge was needed before students could understand scientific and engineering practices, or how scientists ‘do science.’

“Unfortunately, I think the next generation science standards don’t provide the breadth of content knowledge students would need to be able to really think like scientists in a variety of contexts and the content they do provide is not always specified and articulated,” Bruno said in an interview.

The deficiency in content coupled with the lack of clarity specifically in what is expected from teachers means students won’t pick up the content knowledge they need, Bruno added. He believes the standards stress too many things at once and have the potential to overwhelm students.

Ravit Golan Duncan, an assistant professor of science education at Rutgers University, said there has been a continuous shift in the academic world over the past 100 years between teaching the skills needed to do science and focusing more on content knowledge. Far from viewing the NGSS as overemphasizing practices, Duncan sees the standards as a worthwhile attempt to integrate both theory and practice.

“Scientists don’t just sit there coming up with facts; they come up with theories which are these large explanations for how the world works,” Duncan said in an interview. “If we want a public that understands how science is done and scientific knowledge develops, then we need them to understand how those norms and practices and strategies work that scientists’ use.”

This was what the National Research Council, a research body that advises the government on education as well as other matters of public policy, set out to do by drafting the framework for new science guidelines that were later picked up by a consortium of states and ultimately developed into the NGSS.

Bill Badders, president of the NSTA, said there was no way to determine ahead of time how effective the science standards would be, but that he believed they would help improve students’ understanding of science.

“It isn’t perfect,” he said of the NGSS. “But it is the roadmap for what we’re going to be doing and how we should look at standards and science for many years to come.”

Survey: As Common Core enters schools this fall, it’s still a mystery to most Americans

Despite intensifying political battles over the new Common Core State Standards in many states this summer, a new poll shows that a majority of Americans have never heard of them. The new math and English standards, developed to increase rigor in classrooms and better prepare students for college, have been adopted by 45 states and the District of Columbia and roll out in many schools this fall. According to this year’s Phi Delta Kappa/ Gallup Poll of the Public’s Attitudes Toward the Public Schools, 62 percent of those polled said they did not know what the Common Core was.

Among the third of those polled who had heard of these new standards, most were only “somewhat knowledgeable” about the standards. Many Americans also incorrectly believe the standards are being created in all subject areas (they are for math and English language arts), that they are a mixture of new standards and previous state standards (the standards are new) or that the federal government is insisting all states adopt them (the federal government has offered incentives for states to introduce more rigorous standards, but has not required them to adopt the Common Core specifically).

The standards have been in the works since 2009, but in the last few months a backlash has grown, mostly fueled by critics who worry the standards represent federal government overreach. Indiana has successfully passed legislation that would reevaluate implementing the Common Core, while a bill has been introduced in the Pennsylvania legislature that calls for repealing the new standards. In Alabama, four bills intending to prohibit the implementation of Common Core have all failed.

The poll results suggest there could be ongoing difficulties for advocates of the Common Core initiative as they face challenges to the standards across the country.

While an overwhelming percentage of the people polled support the teaching of key goals that proponents say are enshrined in the Common Core, such as bolstering critical thinking and communication skills, 56 percent of those who were familiar with the standards believed they would either make education in the United States less globally competitive or have no effect at all.

Bill Bushaw, the director of PDK International, which published the survey, said the misinformation about the Common Core means proponents should double down on their efforts to inform the public about the changes.

“I think it’s particularly important right now for education leaders across the country to mount information campaigns to help Americans understand what the purpose of the standards are and some of the ramifications that they’ll see with their children in the schools,” he said in a talk with reporters before the release of the poll results on Wednesday.

The president of the American Federation of Teachers, Randi Weingarten, a strong backer of the Common Core, was unsurprised by the findings. In a statement, she said most Americans support teaching children critical thinking skills, but suggested that misperceptions about the standards should be blamed on states that have tied the standards to new, more rigorous tests. (Weingarten recently called for a moratorium on high stakes attached to the standards.)

“It’s also no surprise that Americans have very little knowledge or understanding about the Common Core State Standards, as states and districts, aided by the Race to the Top grants, have defined it through the lens of testing,” she said.

Jamie Gass, director for the Center for School Reform at the Pioneer Institute, an independent public policy research organization, is a critic of the Common Core who says the new standards are dumbing down more rigorous ones already in place in some states.

“The Common Core are not very good standards; they’re simply not as good as the standards that were previously in place in Massachusetts, Indiana, and California,” Gass said in an interview. “So I think people have an intuitive sense that this will not really prepare their children well for competition in the 21st century.”

The poll also found that 58 percent of Americans don’t support evaluating teachers based on standardized tests while only 22 percent believe increased testing helps school performance. But according to an Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research poll released recently, a majority of parents back standardized assessments for their children. Bushaw said the disparity can be explained by the fact that both polls asked the question differently.

Conflicting ideas about how to rate teacher prep programs

After winning a hard-fought battle against the teachers union to impose a new teacher evaluation system, New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg has turned to evaluating the training programs that produce the city’s teachers.

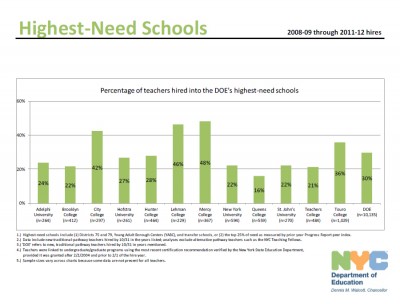

The New York City Department of Education recently released what it dubs as “the nation’s first ever district level Teacher Preparation Program Reports” comparing how well a dozen of the state’s public and private institutions train teacher-candidates. But the findings are, at times, incongruous with those of national teacher preparation ratings released in June.

Those ratings, by the nonprofit advocacy group National Council on Teacher Quality, which has been a vocal critic of teacher preparation programs, were based heavily on education school curriculum and selectivity. The New York City reports focused primarily on the training program’s graduates, including measures such as the percentage of graduates who work in high-needs schools licensed in high-demand areas like science and special education and the percentage that have received tenure. It also evaluates the training programs on how well the teachers they produce scored on the city’s new evaluation system, which is based partly on standardized test scores.

Adelphi University is an example of the discrepancies between the two rating systems – and evidence of the conflict in the field over how best to judge whether teacher education programs are training teachers effectively.

Adelphi’s graduate elementary education program received one out of four stars from NCTQ. Its undergraduate elementary program failed to earn a single star and was labeled with a “consumer alert.”

According to New York City report, however, 68 percent of Adelphi teachers working in the city schools are effective and 12 percent are highly effective – a respectable showing. Teachers College, ColumbiaUniversity, a private program, fared similarly in the New York City rating with 69 percent of its graduates rated as effective and 10 percent highly effective. The school did not provide information about its syllabi and other factors included in the NCTQ rating system, so it didn’t receive an NCTQ rating. (The Hechinger Report is an independent organization housed at Teachers College.)

On the New York City reports, public colleges like those belonging to the City University of New York (CUNY) outperformed some prestigious private schools in certain areas. For example, 82 percent of teachers from CUNY City College were rated effective based on by how much they were able to improve their students’ test scores, compared to 71 percent from New York University. At the top end, the City University of New York and St. John’s University each only had about 10 percent of graduates who fell below the effective rating. Lehman College fared the worst, with a quarter of graduates rated as developing and 14 percent ineffective.

Because of a small sample size of teachers from each institution, the New York City Department of Education recommended interpreting the data cautiously. Unlike NCTQ, the DOE report, which uses data from the last four years, shied away from assigning ratings to schools and in some cases, programs differed starkly on how they fared on each measure. For instance, just 16 percent of QueensCollege graduates go into the city’s highest need schools, the lowest percentage among all the programs. But the school boasts the second highest retention rate with 92 percent of teachers still in the classroom after three years.

Adelphi, Mercy College, and Touro College, all private institutions, led the ranks in how many of their graduates are licensed in high-demand areas, such as math and special education. The reports show that 86 percent of the DOE’s hires from Touro are licensed special education teachers. On the other hand, only 33 percent of New York University teachers in the city schools had a special education license.

The NCTQ system does not have an overall rating for Touro or Mercy College, and only graded them on a couple of features like Common Core content and selectivity. Touro received mixed grades. For example, its elementary graduate program received just one star for Common Core content, while its high school program received four stars for Common Core, something not evaluated in the New York City scorecards.

The mixed results raise the same question plaguing teacher quality ratings: which factors matter most to measure how good or bad a teacher is?

Massachusetts boards performance funding train

With the announcement that Massachusetts community colleges will be funded based on graduation rates and other measures, Hechinger’s Jon Marcus spoke about this national trend on public-radio station WBUR’s Radio Boston program.

The state joins dozens of others in which public higher education competes for dwindling state funding based on outcomes, not just enrollment.

Some states are also imposing penalties for poor performance.

In Massachusetts, the shift is being accompanied by a $20 million—or just under 10 percent—increase in the budget allocation for the 15 community colleges, whose enrollment has ballooned while funding has been relatively flat.

One result is that only about 18 percent of students at the two-year schools receive degrees within even three years, about the same low rate as the national average.

With a lower level of unemployment than most other states, Massachusetts is having trouble filling so-called middle-skills jobs that require associate’s degrees, and businesses have been critical of the community colleges’ record in job training.

The new funding formula will be phased in over three years.

Why did Tony Bennett change Indiana’s school grading system?

In 2010, I visited Christel House Academy, a charter school in Indianapolis that differed starkly from regular Indianapolis public schools. Spanish classes started in kindergarten. In fourth grade, overnight camping trips began and by fifth grade, so did college trips. As part of the school’s focus on project-based learning, a group of middle schoolers were working on a project about the global water crisis, planning to help a village in Tanzania get access to clean water.

Now, the school–a point of pride in the city’s charter sector–is at the center of a grade-changing scandal involving former Indiana State Superintendent Tony Bennett (R.). According to an investigation by The Associated Press, Bennett altered the grade of the popular Indianapolis charter school while he was still in office. Christel House Academy initially earned a C on the state’s accountability system due to poor algebra test scores. But Bennett, now the schools chief in Florida, and his team tweaked the system before the grades were made public and Christel House was given an A.

Although the changes affected grades about a dozen schools, as Bennett has pointed out, Christel House has garnered the most attention. Its founder, Christel DeHaan, is an influential Republican donor. But Christel House has its own political value; it is an important school in the Indiana charter landscape.

“They need to understand that anything less than an A for Christel House compromises all of our accountability work,” Bennett wrote in a Sept. 12 email obtained by The Associated Press.

During his four years at the helm of Indiana’s schools, Bennett became known for his focus on school accountability. He also supported school choice through both vouchers and the expansion of charter schools.

In a city that has seen mixed results with charter schools, Christel House is one of the few that has emerged as a rarely questioned shining star in the charter community. The school, one of the first three charter schools to open in Indianapolis, has been earned praise for more than a decade for demonstrating large test score gains with disadvantaged students. Charter proponents cite it as an example of how freedom of traditional public school bureaucracy can produce impressive results.

In 2010, Christel House added on a high school and in 2012, it started a Dropout Recovery School. It’s since won a grant to develop a charter network, opening up three more schools throughout Indianapolis.

Had the school received a C in the state’s new grading system, after years of being recognized for stellar academic progress, it would have prompted questions, especially from charter school critics, about the school’s accomplishments.

Bennett says the changes to the accountability system had no motive other than fairness for “combined” schools that both elementary and secondary grades. “There was not a secret about this,” Bennett told The Associated Press. “This wasn’t just to give Christel House an A. It was to make sure the system was right.”

Update:

Tony Bennett resigned from his post as Florida Commissioner of Education Thursday, while still defending his changes to the grading system. Still, Bennett said he did not want to become a distraction. “The decision to resign is mine and mine alone, because I believe that when this discussion turns to an adult, we lose the discussion about making life better for children,” Bennett said at a press conference.

Are families reaching the limit for college costs?

Hechinger’s Jon Marcus appears on the radio program Here & Now to talk about a Sallie Mae report that shows what families pay for college has leveled off as parents and students become resistant to further price increases — and universities and colleges have to offer deeper and deeper discounts to fill seats.

In Bihar, hope—and some progress—despite the education system’s many problems

On a 2011 reporting trip to visit schools in Bihar, India’s poorest state, one scene in particular stuck in my mind. After a touring a slum neighborhood on the outskirts of the state’s capital city, Patna, my contact there, Sunita Singh, of the Education Development Center, drove me past a small one-room schoolhouse that served the children who lived crammed in the huts and shabby apartment buildings lining a nearby railway. It was a rickety structure with a dirt floor and thatched roof and walls. It looked like it a strong breeze could knock it down.

I had been scheduled to interview the principal at the school and talk to the students there later in the week. But it was the beginning of the monsoon season and it turned out the building was as fragile as it appeared. Before I could return, a torrential rain came through and destroyed the roof. The school was shuttered until it could be fixed.

The news about the nearly two dozen children who were fatally poisoned by contaminated school lunches in Bihar on July 16 was an even more extreme and horrifying example of the monumental obstacles India faces as it tries to reform its education system.

The country’s economic and political future largely depends on improving the quality of life and the productivity of kids in places like Bihar. With this in mind, in 2009 the country passed a right to education law, which, for the first time, gave children from ages 6 to 14 the right to a “free and compulsory elementary education at a neighborhood school,” meaning a school within a couple of miles of their home. School buildings went up across the country, and the free lunch program became an important incentive for getting impoverished children to show up.

Bihar is one of the main target areas for the reforms. The state is India’s poorest and also one of its most populous. Indian census numbers show Bihar’s population is exploding, with a growth rate of 25 percent. There were 19 million children under the age of 6 in 2011, or 18 percent of the population, and nearly all of them live in rural areas.

In addition to free lunch, girls in rural areas of the state are also given bicycles to further boost the likelihood that they’ll come to school. (The female literacy rate in Bihar was just 46 percent in 2011, according to the Indian census.)

The reforms are making a difference, local officials and education advocates say. In Bihar, “almost 50 percent of students drop out before fifth grade,” said Singh. “But before, they didn’t even enroll.” The 2012 Annual Status of Education Report (ASER), an Indian NGO, found that just 4 percent of the state’s children were out of school. In 2005, it was nearly 14 percent.

Muslim children at a nonprofit school in Bihar, India wait to begin their lessons. (Photo by Sarah Garland)

There is still a long way to go before India reaches the fairly modest goals of the new law, though. As the poisonings and the flimsy school building in Bihar show, the school system is still struggling to ensure basic safety, meaning quality often takes a back seat. ASER found that just 43 percent of rural schools were meeting the law’s requirements for student-pupil ratios—two trained teachers per 60 students. Even when schools have enough teachers, those teachers are routinely absent. In Bihar, the report found that 16 percent of students in the equivalent of third grade couldn’t recognize letters. A third could read their letters, but couldn’t read words. Eleven percent of these students couldn’t recognize the numbers 1 through 9, and a third couldn’t recognize numbers higher than 10.

In addition to its goals for improving elementary and secondary education, India has ambitious plans for its higher education sector. Bihar is experiencing a building boom of new universities and colleges, including plans for a new international university meant to draw students and faculty from around the world.

While I was in Bihar, visiting new state-of-the-art facilities and talking to optimistic administrators, I talked to others who wondered, “Who will go to these schools?” Given the still dire situation in the elementary grades, it remains, two years later, a very good question.

Still, there are lessons to be learned from India’s efforts to improve its education system. The problems of Indian schools can make America’s debates over charter schools and standardized testing seem petty. The growing achievement gaps between the poor and affluent in the U.S. are dwarfed by the even wider divides between wealthy and poor Indians. But although its problems seem overwhelming—endemic corruption, high levels of debilitating poverty and vast numbers of children needing help—India has made huge investments in education and is making significant, if slow, progress toward its goals.

And despite the frustrations and disappointments, there is also a lot of hope. The appetite for education in Bihar is ravenous.

On another day during my visit to Bihar, I visited an education program for Muslim children run by a local nonprofit organization. In the state’s Muslim community, which is both large and “steeped in poverty,” according to a 2004 report by local researchers, girls are often discouraged from attending school. Many stay at home and do piecework to support their families. The nonprofit had set up its programs to provide them more flexibility than the regular public schools do—the girls could come during part of the day and practice their numbers and letters, and spend the rest of the day working.

At one of the nonprofit’s centers, small children sat in circles on the floor hunched over workbooks in Urdu, Hindi and English. They were receiving extra tutoring from college student volunteers while regular classes were out. But among them were two teenagers, Nazia and Tazia Hassan, who had spent their elementary school years making saris.

Their father was poor, they said, and had depended on their contribution to get food on the table. Times had changed, though, and the girls said he had begun to see the value of an education. Tazia, 14, said that her goal was to eventually become a doctor. Nazia, 16, had vaguer plans, but thought she might try college someday. “No one will value you if you’re not educated,” she said in Urdu through a translator. “I want to go as far as possible.”

New lawsuit an ‘assault’ on unions

A California lawsuit filed this spring against teachers unions could have widespread national implications for labor laws. Ten non-union teachers and the Christian Educators Association are suing their local, state and national unions, alleging that the organizations are forcing them to pay to support political activities they do not agree with in violation of their first amendment rights.

The plaintiff’s lawyers are attempting to fast-track the case in the California courts by essentially eliminating the discovery phase and then appealing almost immediately to the U.S. Supreme Court. A decision in their favor could turn every state in the country into a right-to-work state, where public employees can opt out of joining a union.

Wisconsin union members march in protest of a law that reduced their collective bargaining rights. (Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

The unions say that they are complying with existing law and the California Constitution. California Teachers Association (CTA) officials see the suit, which was filed on behalf of the plaintiffs by a conservative group, as part of a broader mission by the right to weaken public sector unions – a legal counterpoint to legislative efforts around the country. Since 2010, three states – Indiana, Michigan and Wisconsin – have passed and maintained laws restricting labor rights.

While other groups have tried for decades to use the courts to reduce union strength, this case is particularly aggressive, said CTA’s legal director Laura Juran. “This is a full-frontal assault,” she said.

In 24 states, including California, teachers and other public workers are automatically enrolled in unions. Individuals are allowed to opt out, but few do. Those that do are still required to contribute agency fees that go toward the union’s collective bargaining efforts because they are covered by the contract the union negotiates.

The courts have held for decades that unions can’t charge these non-members for political activity, though. If the Supreme Court agrees to hear the case once it has gone through the lower courts the California, plaintiffs want the justices will go a step further and rule that a worker who opts out of a union should not have to pay for any of the union’s activities. While it is unclear if the lawsuit will reach the highest court, California union officials are worried about the potential results.

“If the U.S. Supreme Court holds that it is unconstitutional to require public employees to contribute to a union’s collective bargaining expenses, even when those employees directly benefit from the collective bargaining agreement, this would be tantamount to sanctioning free riding and would have a profound impact on public sector unionism in the United States,” said Benjamin Sachs, a professor at Harvard Law School and an expert on labor law.

Following a 1980 decision, unions are required to give out notices to all non-union members explaining which activities they are being charged for and which they aren’t. But some labor experts question the validity of these self-reported notices and say breaking down a union’s many activities is a murky business.

The expenses are not confined to the negotiating table. In the 2012-2013 school year, for instance, the California Teachers Association reported that a $27,860 “Ethnic Minority Early Identification Development program” and $18,079 “special publications” were related to collective bargaining. Also that year, the union hosted a Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender (GLBT) Conference to “address issues involving GLBT educators, students and community” and found that nearly 87 percent of its cost – or $65,099 – was eligible to be paid for by agency fees.

The conference, and another gay and lesbian program, is one of the specific examples the plaintiffs take issue with. “Whatever you think about these programs, they are not related to collective bargaining,” said Terry Pell, president of the Center for Individual Rights, the right-leaning organization that filed the lawsuit on behalf of the plaintiffs. (The plaintiffs are also represented by Jones Day, one of the country’s largest corporate law firms.)

Although Juran could not speak to the specifics of the GLBT conference, she said that it, like other CTA events, likely was designed to promote safety and inclusion for all teachers and students. Much of the activity that the union labels as part of its collective bargaining efforts relates to working conditions and improving education, she added.

The union is careful about documenting staff time to accurately breakdown chargeable and nonchargeable activities and “tends to err on the side of not charging,” Juran said.

But the complaint also argues that collective bargaining in itself is a political activity. For instance, many teachers unions across the country have opposed merit pay in contract negotiations, despite the fact that individual teachers may support it. “The distinction between political expenditures and collective bargaining is a made-up distinction,” Pell said. “Collective bargaining is every bit as political as what unions call overtly political.”

Unions have historically argued that agency fees serve as an important protection against the “free rider problem,” where, in theory, all workers could choose not to join the union if they get the contract negotiations for free. Pell dismissed that argument, pointing to union membership in right-to-work states. Although the numbers vary widely, in most right-to-work states that allow collective bargaining, anywhere from half to about 80 percent of teachers are unionized.

Pell, and other legal experts, see a potential opening for change based on a 2012 Supreme Court decision. In that case, Knox vs. Service Employees International Union, Local 1000, the justices ruled that unions must have members “opt in” to any special fees, rather than automatically deduct them.

Justice Samuel Alito, writing for the majority, suggested in his opinion that the merit of agency fees in general was suspect. “Because a public sector union takes many positions during collective bargaining that have powerful political and civic consequences, the compulsory fees constitute a form of compelled speech and association that imposes a significant impingement on First Amendment rights,” Alito wrote.

His argument, which pushed beyond the scope of the questions raised in Knox, gives Pell and his colleagues hope that they’ll be able to get the Supreme Court’s attention. Alito is one of the court’s most conservative members, however, and Sachs noted it was still unclear if they would have the four votes necessary for the court to accept the case.

“There are at least some justices on the Supreme Court who are wondering out loud about the constitutionality about dues requirements,” Sachs said. “That probably means that some of them would like to have such a case.”

Charter performance improving, but still varied

Since Stanford University’s Center for Research on Education Outcomes (CREDO) released a report on charter schools in 2009 that prompted questions about how well these schools were serving students, the sector has continued to grow. In the past four years, national charter school enrollment has increased by 80 percent to 2.3 million students.

CREDO’s latest comprehensive report checks back in with the charter movement and concludes that charter performance has improved since 2009 – but finds charter schools that outperform traditional school districts are still the exception rather than the rule.

The original CREDO study, which looked at charters in 15 states and the District of Columbia, made headlines with the finding that just 17 percent of charter schools significantly outperformed their district counterparts in math. Charter school students performed worse in both math and reading than their equivalent peers in the traditional public school system.

The newest study looks at the original states plus nine others and New York City. All told, it covers 95 percent of the nation’s charter school students. The researchers found that charter school students are now ahead of traditional public school students by seven days in reading and behind by seven days in math.

At the same time, the gap between how charter and traditional school students perform has narrowed significantly. The Stanford researchers say the change was partially due to the closure of low-performing charter schools as well as a decline in achievement among public school students.

While performance varied considerably from state to state, overall a quarter of charter schools significantly outperformed traditional public schools in reading and 29 percent did so in math. Nineteen percent of charters did significantly worse in reading and 31 percent scored worse in math.

“There remain worrying numbers of charter schools whose learning gains are either substantially worse than the local alternative or are insufficient to give their students the academic preparation they need,” the study said.

More than half of all charter school students are eligible for free- or reduced-priced lunch. Given their findings, the CREDO researchers concluded that charters are not closing the achievement gap—which is the stated goal of many of these schools. Minority and low-income students in charter schools typically learn more annually than their peers in traditional schools, but white students in the traditional system still outpace them.

The overall numbers hid important differences in performance within student groups, the study also found, suggesting that charters do offer certain students a significantly better experience than they would find in a regular school.

The more disadvantaged the student is, for example, the better they do in comparison to similar students in district schools. Black charter school students did not learn significantly more in reading or math than black students in traditional schools, but low-income, black students were ahead of their counterparts in traditional schools by 29 days in reading and 36 days in math.

“We don’t think seven days is very substantial,” said Devora Davis, research manager at CREDO. But jumping ahead by a month? “That’s starting to look pretty substantial.”

Supreme Court leaves affirmative action intact, for now

The Supreme Court released an anti-climatic ruling in what might have been a major decision about the use of race in higher education admissions on Monday. In its decision, the court sent the case back to the Fifth Circuit with instructions for the lower court to re-examine how the University of Texas (UT) uses race in its admission system.

The 7-1 decision—which does not appear to have any immediate wider, national implications—is no doubt provoking some sighs of relief among university presidents and admissions officers around the country who have staunchly defended the use of race in their admissions systems.

Minority students at the University of Texas-Austin have higher graduation rates than at less-selective institutions, but the rates are still lower than for white students. (photo by Sarah Garland)

The lower court did not use “strict scrutiny,” a term used by the courts when constitutional rights are abridged, to examine whether the university’s use of race was justifiable. Rather, the Fifth Circuit deferred to the judgment of the school. When a court uses strict scrutiny to examine a situation where race is used, it must find that the institution uses a plan that has “compelling interest” and is “narrowly tailored,” meaning, essentially, that it is sufficiently focused on the goal at hand: increasing diversity in the student body.

Justice Anthony Kennedy, generally seen as the often right-leaning swing vote on many issues that face the court, including race, wrote the short opinion. “Under Grutter, Strict scrutiny must be applied to any admissions program using racial categories or classifications,” Kennedy wrote, referring to a case in 2003–the last time the court ruled on affirmative action.

The plaintiff was a white student, Abigail Fisher, who was denied admittance to UT in 2008. She was part of a small section of the student body who are not admitted to the university under a race-blind system in which the school admits high school students in the top 10 percent of their graduating class. Race is an element of one of seven factors that the institution uses to rate applicants who aren’t admitted through the top 10 percent program.

Given that the lower court was sympathetic to the University of Texas, it seems likely that the Fifth Circuit will not overturn the school’s admissions system when it takes a second, more intensive look, because race is a relatively small factor—although we’ll have to wait and see.

The decision may seem like a blow to critics of affirmative action, who have argued that the use of race is unfair and were hoping the court would rule definitively against it. Some proponents of increased diversity in schools had also hoped that a decision that curtailed the use of race might push institutions to consider other factors, especially socio-economic status.

But the New York Times reports that legal experts believe the decision opens the door to additional challenges to affirmative action plans at public universities and “say it is only a matter of time before similar challenges are filed against private colleges, as well – and they are likely to succeed.”

The Hechinger Report will be keeping tabs on reactions and updating this post throughout the day.

Updates:

The last time the Supreme Court ruled in a major case involving race in education was in 2007, when Kennedy cast the deciding vote in a ruling that said elementary and secondary schools can’t use race as the sole factor when assigning students.

Back then, both proponents and critics of race-based admissions found reasons to be both pleased and frustrated with the decision. Although the court had made it more difficult for schools to use race to increase diversity among students, it had not struck down the use of race outright.

Kennedy’s ruling on Monday is similarly incremental and ambiguous about what the long-term consequences might be, as the responses from both sides of the affirmative action debate highlight.

“The Supreme Court has established exceptionally high hurdles for the University of Texas and other universities and colleges to overcome if they intend to continue using race preferences in their admissions policies,” said Edward Blum, an activist (and UT alum) who organized the legal challenge against the university, in a statement reported in the Washington Post. “It is unlikely that most institutions will be able to overcome these hurdles.”

The Association of Public and Land-grant Universities wrote in an emailed statement that its members would try to ensure diversity among students and faculty in the wake of the decision, although “it will take some time for us to fully process what this ruling means for our universities.”

Attention now reverts back to Texas from Washington, D.C. (or more precisely, to New Orleans, where the appeals court is located). The Fifth Circuit will reexamine the UT program with a stricter lens to decide whether the university’s consideration of race for some students is necessary alongside its larger race-neutral program that is also meant to ensure diversity.

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg, the lone dissenter, noted in her opinion that the university’s top 10 percent system is able to ensure diversity mainly because it relies on extensive racial segregation among Texas’s secondary schools.

“Only an ostrich could regard the supposedly neutral alternatives as race unconscious,” she wrote. “Texas’ percentage plan was adopted with racially segregated neighborhoods and schools front and center stage.”

Still, at Bloomberg News, Noah Feldman suggested that when the appeals court looks again at UT’s race-conscious system, it “might well say there must be some other way to accomplish this.”

For a look at what affirmative action–and its demise–have meant at the state level for minority enrollments in higher education, check out this series of graphics from the New York Times.