After winning a hard-fought battle against the teachers union to impose a new teacher evaluation system, New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg has turned to evaluating the training programs that produce the city’s teachers.

The New York City Department of Education recently released what it dubs as “the nation’s first ever district level Teacher Preparation Program Reports” comparing how well a dozen of the state’s public and private institutions train teacher-candidates. But the findings are, at times, incongruous with those of national teacher preparation ratings released in June.

Those ratings, by the nonprofit advocacy group National Council on Teacher Quality, which has been a vocal critic of teacher preparation programs, were based heavily on education school curriculum and selectivity. The New York City reports focused primarily on the training program’s graduates, including measures such as the percentage of graduates who work in high-needs schools licensed in high-demand areas like science and special education and the percentage that have received tenure. It also evaluates the training programs on how well the teachers they produce scored on the city’s new evaluation system, which is based partly on standardized test scores.

Adelphi University is an example of the discrepancies between the two rating systems – and evidence of the conflict in the field over how best to judge whether teacher education programs are training teachers effectively.

Adelphi’s graduate elementary education program received one out of four stars from NCTQ. Its undergraduate elementary program failed to earn a single star and was labeled with a “consumer alert.”

According to New York City report, however, 68 percent of Adelphi teachers working in the city schools are effective and 12 percent are highly effective – a respectable showing. Teachers College, ColumbiaUniversity, a private program, fared similarly in the New York City rating with 69 percent of its graduates rated as effective and 10 percent highly effective. The school did not provide information about its syllabi and other factors included in the NCTQ rating system, so it didn’t receive an NCTQ rating. (The Hechinger Report is an independent organization housed at Teachers College.)

On the New York City reports, public colleges like those belonging to the City University of New York (CUNY) outperformed some prestigious private schools in certain areas. For example, 82 percent of teachers from CUNY City College were rated effective based on by how much they were able to improve their students’ test scores, compared to 71 percent from New York University. At the top end, the City University of New York and St. John’s University each only had about 10 percent of graduates who fell below the effective rating. Lehman College fared the worst, with a quarter of graduates rated as developing and 14 percent ineffective.

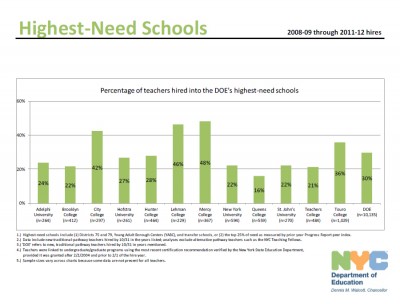

Because of a small sample size of teachers from each institution, the New York City Department of Education recommended interpreting the data cautiously. Unlike NCTQ, the DOE report, which uses data from the last four years, shied away from assigning ratings to schools and in some cases, programs differed starkly on how they fared on each measure. For instance, just 16 percent of QueensCollege graduates go into the city’s highest need schools, the lowest percentage among all the programs. But the school boasts the second highest retention rate with 92 percent of teachers still in the classroom after three years.

Adelphi, Mercy College, and Touro College, all private institutions, led the ranks in how many of their graduates are licensed in high-demand areas, such as math and special education. The reports show that 86 percent of the DOE’s hires from Touro are licensed special education teachers. On the other hand, only 33 percent of New York University teachers in the city schools had a special education license.

The NCTQ system does not have an overall rating for Touro or Mercy College, and only graded them on a couple of features like Common Core content and selectivity. Touro received mixed grades. For example, its elementary graduate program received just one star for Common Core content, while its high school program received four stars for Common Core, something not evaluated in the New York City scorecards.

The mixed results raise the same question plaguing teacher quality ratings: which factors matter most to measure how good or bad a teacher is?