How about shopping for a college degree at Wal-Mart?

It seems one giant– and much maligned — retailer is taking President Barack Obama’s challenge to make sure more students get college degrees very seriously: That would be Wal-Mart, according to The New York Times .

The story says Wal-Mart will work with a Web-based university to offer affordable college degrees to its employees, who can earn college credits while performing their regular duties.

So exactly why is it such a big deal? After all, lots of companies help their employees get degrees. The move by Wal-Mart is huge because of the sheer size of the company work force — some 1.4 million Americans work at the discount retail chain.

“If 10 to 15 percent of employees take advantage of this, that’s like graduating three Ohio State Universities,” Sara Martinez Tucker, a former under secretary of education who is now on Wal-Mart’s external advisory council, told The Times. “It’s a lot of Americans getting a college degree at a time when it’s becoming less affordable.”

How promising an idea is it? And what are the implications? Is this a publicity gimmick or a genuine attempt to help Americans get better educated?

Race to the Top: Predicting round-two winners

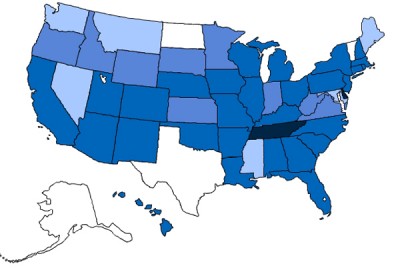

The second-round application deadline for the Race to the Top competition has now passed. Thirty-five states and Washington, D.C. applied. Which ones will win?

Secretary of Education Arne Duncan has indicated that 10-15 states are likely to receive grants this time around, up from just two winners — Delaware and Tennessee — in the first round of the competition.

Here are my predictions for which states stand the best chance of winning a piece of the $3.4-billion pie (in alphabetical order):

Colorado

Florida

Georgia

Illinois

Kentucky

Louisiana

Maryland

Massachusetts

North Carolina

Ohio

Pennsylvania

Rhode Island

South Carolina

Washington

Washington, D.C.

Colorado, which finished a distant 14th out of 16 finalists in the first round, seems to have improved its chances considerably by passing bold legislation last month that will link teacher evaluations to student achievement.

Rhode Island, which placed eighth in the first round, may have burnished its image and application courtesy of Central Falls High School. The school made headlines in February when the superintendent decided to fire all of its teachers at the end of the current academic year as part of her “turnaround” plan for the troubled institution.

The dramatic step won nods of approval from Arne Duncan and even President Barack Obama, who himself weighed in on the issue: “If a school continues to fail its students year after year after year, if it doesn’t show signs of improvement, then there’s got to be a sense of accountability. And that’s what happened in Rhode Island last week.” (Last month, however, an agreement was reached between the superintendent and the teachers’ union that will allow all Central Falls teachers to keep their jobs come this fall.)

Florida’s chances in the second round might have been compromised somewhat by Gov. Charlie Crist’s decision in April to veto a bill that would have radically altered how the state’s teachers are paid and gain tenure. But Florida finished fourth the first time around and thus will probably sneak into the top 15 in the second round.

The biggest unknown is how the six states that applied only in the second round will fare. Maine, Maryland, Mississippi, Montana, Nevada and Washington have all taken the plunge for the first time. How will they do? I’ve got my money on Maryland and Washington in this group.

Which states do you think are most likely to win — and why?

Assignment memo: Dual-enrollment programs spread

Here’s another story we’re working on. Share your thoughts.

Twenty-five years ago, Minnesota’s Post Secondary Options program became the first state-funded effort allowing high-school students to earn credits at a college or university — at no charge to their families.

More than 100,000 Minnesotans have saved a bundle of money on tuition over the years, but critics say PSEO serves mostly white, middle-class students despite growing minorities and a troublesome achievement gap.

Meanwhile, the new generation of dual-enrollment programs sprouting across the nation is intensely focused on under-represented and at-risk students and seeing some encouraging results.

What’s next for Minnesota and other dual-credit programs?

Which American will be next to win the Nobel Prize in Literature?

I recently had a chance to ask Toni Morrison the following question: which American author alive today is most deserving of the Nobel Prize in Literature? Morrison — who remains the most recent American laureate for the literature prize, which she won in 1993 — said she wished an American would win it again soon so silly people like me would stop asking her such questions.

Then, savvily skirting my question, Morrison said that American playwrights are too often overlooked. She didn’t name any living authors deserving of the prize, which was obviously the safest move to make. (Since 1974, Nobel regulations state that the prizes cannot be awarded posthumously, unless a would-be recipient dies between the announcement [typically in October] and the actual award ceremony [typically in December].) But Morrison did go on to point out that two of America’s greatest playwrights, Arthur Miller and Tennessee Williams, never won the Nobel Prize in Literature — but they almost certainly should have.

I agree.

Miller won a Pulitzer Prize in Drama for Death of a Salesman (1949), while Williams won two Pulitzers, one for A Streetcar Named Desire (1948) and one for Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1955).

Winning the Nobel Prize in Literature is important, among other reasons, because it brings one’s work to new audiences. Teachers of literature around the world fill their syllabi with the work of Nobel laureates. As the world’s most prestigious lifetime achievement award, the Nobel Prize in Literature bestows a certain legitimacy on one’s work and ensures that audiences around the globe will read it. Every October when the latest winner is announced, publishing houses quickly turn out new editions of the winner’s works. High schoolers soon find themselves studying them.

I vividly recall my first encounter with Toni Morrison’s work. My required summer reading between sophomore and junior year of high school, in 1993, consisted of John Grisham’s A Pelican Brief and Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye. My teacher’s thinking was that we’d compare and contrast “escape” fiction (Grisham) with “real” or “serious” fiction (Morrison). Unsurprisingly, we all emerged from that assignment scorning “escape” fiction and shunning everything by John Grisham, Michael Crichton and Stephen King. Anything that was easy to read and nothing more than plot was out. Symbolism and foreshadowing were in, as was language so complex that rereading was not just advisable but essential. I’ve been a literary snob ever since.

Morrison’s The Bluest Eye broke my heart, but I loved it. I went on to read all nine of her novels. My favorite to teach is Song of Solomon (1977), which at 337 pages is quite a challenge for many students to get through. But they always do, and they (almost) always love it.

So who do you think will be the next American to win the Nobel Prize in Literature? Who most deserves it, and why? (I’ve got my money on Philip Roth and Joyce Carol Oates.) Will the American drought end in 2010?

In tough economy, Illinois colleges turning down financial aid requests

A headline on an Associated Press story revealed what could become — and what in many cases already is — an extremely troubling situation for potentially hundreds of thousands of college students across the country: Illinois Turns Away 27,000 for Financial Aid.

“The agency that distributes the payments (The Illinois Student Assistance Commission) says an increase in demand has forced it to turn down almost 27,000 students, and that figure could grow to 200,000 by fall,” the story notes. Last year, ISAC provided more than 183,000 grants worth $430 million.

But there hasn’t been enough money in recent years for all the students who request aid; the story says some 120,000 students who were eligible for ISAC’s monetary award program were turned down, and almost 60,000 the year before. This year, though, the numbers will be far more dramatic as more students and their families are struggling to pay for college or staying in school longer because they can’t find jobs.

Some colleges, like the University of Illinois‘ flagship campus in Urbana–Champaign, are finding money to make up the difference; the school plans to spend more than $40 million on supplemental financial aid next year, the story notes.

And what will happen to all the students who are being turned down? Loans are likely their only option. Last year, some private schools took up the slack and offered attractive aid packages, while some public universities were criticized for handing out aid to wealthier students.

In the meantime, there are plenty of other examples. According to a report released this week by the Washington D.C. based Center on Budget and Priority Policies, at least 41 states have cut assistance to public colleges and universities, resulting in reductions in faculty and staff in addition to tuition increases. Michigan and New Mexico, meanwhile, have made deep cuts to need-based financial aid programs as well.

Who said or didn’t say what? A little tiff between the AFT and Steven Brill

Steven Brill’s New York Times Magazine piece entitled “The Teachers Unions’ Last Stand,” is creating a rift, naturally, between Brill and the American Federation of Teachers leader Randi Weingarten.

The AFT issued a “talking points,” memo noting that the article unfairly labels teachers as “bad,” and “caricatures contract negotiations as an exercise in which administrators prevail upon unions to concede to enlightened reforms and unions doggedly resist.”

The memo also noted that Brill made up a quote and falsely attributed it to Weingarten, according to Eduwonk.

Brill, for his part, responded, and denied it. No tape recording exists of this interview, so anyone who wants to dig through it all will just have to read the memos or allow the larger debate on education reform to continue to unfold.

Assignment memo: Is Massachusetts already at “The Top?”

Fairly regularly, The Hechinger Report will be posting quick summaries of stories we are working on to give you a sneak peek at what we are working on and what you’ll see in upcoming weeks.

More importantly, it gives folks a chance to raise questions and make suggestions before the story is completed. Now is your chance to help mold our coverage.

Here is our first Assignment Memo:

As the June 1 deadline for Obama’s Race to the Top competition approaches, Massachusetts is intensely debating whether Race to the Top is a race worth winning, especially when it comes to setting new national standards as part of their application. Massachusetts leaders say they’ve already spent considerable time and effort developing high standards and that their students rank at or near the top of national and international tests. They wonder: Would adopting the national baselines actually be a step down?

Here’s a few stories and op-ed pieces on the issue:

Arne Duncan urges Mass. to reapply for Race to the Top

Mass. education officials considering changing test

Op-ed: Is changing the test selling out?

Op-Ed: State shouldn’t adopt weaker standards

From the heartland: A struggle to improve education for all

Sometimes it feels like the issues of large, urban school districts get all the attention. It’s one reason why The Hechinger Report was captivated by news of a study that appeared in the American Association of School Administrators journal, one that looked at how small towns are educating — and retaining — their high schoolers. Turns out, there is much work to be done to keep the best and the brightest from fleeing.

Between 1980 and 2000 more than 700 non-metro counties lost at least 10 percent of their population, and between 2000 and 2005 more than half of all such counties have had more deaths than births, writes Rutgers University sociologists Patrick Carr and Maria Kefalas.

The story includes findings of the time they spent researching their book on education in a small Iowa town, “Hollowing out the Middle.”

“Though young people always have left small towns to seek their fortunes elsewhere, these losses are more debilitating now because of the economic transformations that have profoundly restructured opportunities for those who stay in these communities that have so long depended on vulnerable manufacturing and agricultural sectors,” the story noted. “Put simply, a generation ago, the loss of educated young people was not as devastating because of the opportunities in the mid-20th-century economy that sustained those who stayed in or returned to small towns through work in factories or on family farms,” the article notes.

The authors’ MacArthur Foundation sponsored study of young adults in 21st-century America allowed them “to learn how young people coming of age in the countryside compared to their metropolitan peers in Minneapolis-St. Paul, New York and San Diego.”

What they found did not bode well for the future of small towns, so the husband and wife team came up with plenty of recommendations as a result of their work, from taking better steps to prepare young people for jobs in shortage areas to partnerships with local community colleges to training and internship programs that link employers to high school students.

“Rethinking education is perhaps the key to arresting the decline and building for the future, ” they note.

Outliers: Child Prodigies

Earlier this week, I blogged about Malcolm Gladwell’s third book, Outliers: The Story of Success (2008). Near the end of the book, Gladwell cites research by Alan Schoenfeld, a professor in the Graduate School of Education at the University of California, Berkeley, that suggests why some students succeed at math while others don’t. What does success in math ultimately boil down to? Attitude, not aptitude, Schoenfeld says. Gladwell explains: “Success is a function of persistence and doggedness and the willingness to work hard for twenty-two minutes to make sense of something that most people would give up on after thirty seconds.”

Among Gladwell’s various other claims is that “[S]uccessful people don’t do it alone. Where they come from matters. They’re products of particular places and environments.” That is to say, usually it’s not enough to be good — or even great — at something. Support systems, the right timing and just plain ol’ luck also play important roles.

This is something I’ve always believed in my gut: individual effort matters most of all, though it alone generally proves insufficient. Incredible individual effort is simply the first step on the way to success. An early start is often indispensable. Sidney Crosby, who at 22 has already led the Pittsburgh Penguins to a Stanley Cup and Team Canada to a gold medal in this year’s Winter Olympics, started playing hockey at age 2. He could skate by age 3.

Mozart, of course, was composing by age 5. It didn’t hurt that his father was a music teacher and composer who held a prominent position in the Archbishop of Salzburg’s court orchestra. Mozart was supernaturally gifted, but he also had a supportive — some would say exploitative — father. By the age of 6, Mozart was traveling around Europe and playing for the most important figures of his day.

Justin Snider Speaking with "Billy Elliot" Giuseppe Bausilio After the May 9th Performance (Photo by Sonny Datoy)

Another child prodigy, and one whom I’ve had the privilege to teach, is Giuseppe Bausilio. He’s currently starring in the Chicago production of Billy Elliot: The Musical.

Giuseppe’s success is the result of an early start — he began ballet at age 4 — and a very supportive family with dance deep in its blood. Both of Giuseppe’s parents were ballet dancers in their younger years and now they run ballet schools in Switzerland; his brother is a ballet dancer as well.

Two weeks ago I was in Chicago and had a chance to see Giuseppe on stage. Wow! He was nothing short of fantastic, and the standing ovation was more than well-deserved.

The lead role of this musical is so demanding that four boys share it in Chicago; on Broadway, five boys are currently playing Billy. They must be exceptional at ballet, of course, but they must also be skilled at singing, acting and modern dance. It’s no wonder that Billy Elliot — which premiered in London five years ago — has conducted worldwide searches each time it has sought “new” Billys. I have been lucky enough to see Billy Elliot in London, New York and Chicago, and I’m always struck by the professionalism of the young actors. It’s hard to believe that anyone can pull off some of the show’s moves — and it’s all the more incredible that 12- and 13-year-olds can.

If you have yet to see Billy Elliot, I strongly suggest you make it a top priority. And if you don’t happen to live in one of the cities where it’s currently playing, you might just be in luck. A U.S. National Tour will begin later this year. The musical will also be opening in Seoul, South Korea this August and in Toronto, Canada next February. You’ll be awe-struck by the sheer talent of the young performers.

As Gladwell says, “It is not the brightest who succeed. … Nor is success simply the sum of the decisions and efforts we make on our own behalf. It is, rather, a gift. Outliers are those who have been given opportunities — and who have had the strength and presence of mind to seize them.”

Once again, NAEP scores not terribly promising

The nation’s report card shows, once again, that U.S. students are struggling at the middle school level and not posting much needed gains in literacy. The results come just six months after the National Assessment of Education Progress or NAEP, exams showed U.S. students also lagging in math.

U.S. Education Secretary Arne Duncan told the Wall Street Journal in an interview on Thursday that the U.S. will have to tackle “the tough reading challenges in middle school,” to improve results. He found some good news, though: he said in a press release that the reading achievement of students in the largest cities has increased over time, and that both Atlanta and Los Angeles had experienced increases in fourth and eighth-grade.

The exam is given every two years to students across the U.S. New York City’s fourth-graders showed some gains, but eighth-graders are still struggling.

Atlanta, it turns out, had the fastest reading gains of any city, boosting scores 14 points in both the fourth and eighth-grade since 2002.

Randi Weingarten, president of the American Federation of Teachers, called the results “a mixed bag,” on Thursday but said there is a lot to learn from the districts that posted gains. “Districts such as Atlanta are making progress because they use a strong curriculum, and teachers are getting the right resources, training opportunities and the time to work with their colleagues and students,” she said in a statement.

The most discouraging news came from Detroit, where the public school students scores were the worst in the U.S.