A New Jersey miracle? Perhaps.

Should education reporters be flocking to New Jersey to write about its graduation “miracle”?

Should education reporters be flocking to New Jersey to write about its graduation “miracle”?

A report by the Schott Foundation for Public Education released this week showcases New Jersey, and Newark in particular, as a rare bright spot in a dismal picture of graduation rates for black males in America, and the report’s authors attribute New Jersey’s superior performance to the state’s preschool program in low-income districts.

But, as so often happens in education, this isn’t quite an unqualified success story.

As Jay Mathews writes over at The Washington Post, even New Jersey officials are suggesting that the numbers may not accurately reflect what’s happening on the ground.

For one thing, the data are self-reported by districts, and graduation rates are notoriously slippery calculations.

Another issue is New Jersey’s controversial Special Review Assessment, the alternative test that high school students used to take if they failed the state’s high school exit examination, which is required for graduation. This test has been phased out, but it was still in effect for the 2007 graduation rates used in the Schott report. The fail rate on this earlier alternative test was only 4 percent. The Christie administration introduced a new, much harder alternative test this year, saying the prior one inflated graduation rates.

Still, New Jersey has made gains on more objective ratings, like the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP). Although the gap between white and black students’ NAEP scores is still wide in New Jersey, it has narrowed in recent years. The Schott report notes that the state is one of the top two in reading scores for black eighth-grade boys.

So whether or not it should be classified as a “miracle,” there’s certainly something going on in New Jersey.

—

Note: The Schott report used data from the Common Core of Data published by the U.S. Department of Education; it’s the same data that Education Week uses to do its annual analysis of national graduation rates. The Ed Week report this year didn’t single out Newark or any other district in New Jersey in its 21 “beat-the-odds” urban districts.

Recess round-up: August 18, 2010

A daily dose of education news around the nation – just in time for a little mid-day break!

Community colleges: In Boston, some students are burning the midnight oil in an attempt to move from a job to a career.

(Inside Higher Ed)

Insider’s guide: HerCampus is a collegiette’s guide to campus life. (WomenRising)

EduJobs: Despite last week’s federal legislation that will give states $10 billion to preserve teachers’ jobs, some school districts are reluctant to spend the money right away. (The New York Times)

Stay or go? Sam Chaltain, a Washington, D.C.-based educator and strategist, discusses whether the District of Columbia would be better off with or without Schools Chancellor Michelle Rhee come this fall. (The Washington Post)

Technology: Former Govs. Jeb Bush and Bob Wise launched the Digital Learning Council today to develop a set of best practices for digital education that states would then be encouraged to adopt. (Education Week)

Reform: Twenty years after the landmark Kentucky Education Reform Act was adopted, Gov. Steve Beshear convened community forums throughout the state to discuss ways to improve public education. (Courier-Journal)

Higher ed: A $420 billion industry. Diane Rehm talks with two professors about tenure and whether everyone should go to college. (WAMU via National Association of Independent Colleges and Universities)

No more books: Some schools in Wisconsin are ditching textbooks for “netbooks.” The mini-laptop computers will save the schools money over the long term and spare kids the aching backs. (Sheboygan Press)

Colleges that graduate students deep in debt

If April showers bring May flowers, what does July heat bring?

Not August meat.

August is instead open season on college rankings — which are, of course, mostly fluff. The idea that the overall quality of U.S. colleges and universities can be reduced to a single number, which allows institutions to be rank-ordered first to last, is hugely problematic.

But it’s also hugely popular.

America has a love affair with Top 10 lists, and not just of the David Letterman variety. We love rankings — largely because they provide an easily digestible way in our busy and complex world to know, or think we know, which things are better than other, similar things. U.S. News & World Report has been a leader in the field of rankings, putting out lists since time immemorial not just on the top U.S. colleges and universities, but also on everything from the country’s best hospitals, health plans and nursing homes to the best cars, trucks and hybrids.

America has a love affair with Top 10 lists, and not just of the David Letterman variety. We love rankings — largely because they provide an easily digestible way in our busy and complex world to know, or think we know, which things are better than other, similar things. U.S. News & World Report has been a leader in the field of rankings, putting out lists since time immemorial not just on the top U.S. colleges and universities, but also on everything from the country’s best hospitals, health plans and nursing homes to the best cars, trucks and hybrids.

What are the best mutual funds? U.S. News will tell you. The best places to retire? The magazine’s got that covered, too.

Today, U.S. News & World Report released its “Best Colleges 2011” rankings, and the usual suspects again topped the lists: Harvard, Princeton and Yale in the “national universities” category, and Williams, Amherst and Swarthmore in the “national liberal arts” category.

Elsewhere, these schools didn’t fare too well. The “What Will They Learn?” rankings, a project of the American Council of Trustees and Alumni (ACTA), gives Yale, Williams, Amherst and Swarthmore each an F for requiring students to take one or zero courses in its favored subject-areas (composition, literature, foreign language, U.S. government or history, economics, mathematics, and natural or physical science). Princeton escaped with a C for requiring three courses in these seven areas, while Harvard squeaked by with a D (requiring two of the seven).

Forbes, meanwhile, entered into the rankings fray in 2008. Interestingly, its rankings take into account the average amount of debt that students graduate with, as well as the rate at which students in a given institution default on their loans. Student debt-load and loan-defaults are on everyone’s mind right now because of the tough economy, but also because of recent inquiries into the for-profit college industry initiated by Sen. Tom Harkin (D-IA).

Last Friday at 5:15 pm, when most of the country had checked out for the weekend, the U.S. Department of Education quietly published four-year loan-repayment rates and average debt-load for students at over 8,400 institutions of higher education. The for-profit industry went into a tailspin for the second time in as many weeks because the repayment rates and debt-loads of students at for-profit colleges were bleaker than many had hoped or expected. (For-profits were also shaken on August 2nd when a report by the Government Accountability Office found deceptive recruiting practices at all 15 institutions it had secretly investigated.)

According to an August 14th article in The New York Times, “outside advocacy groups that analyzed the data found that in 2009, [loan-] repayment rates were 54 percent at public colleges and universities, 56 percent at private nonprofit institutions, and 36 percent at for-profit colleges.”

Repayment rates and average student debt-loads for all 8,400 institutions can be found here. A few institutions did manage to have 100 percent repayment rates — the 4-States Okmulgee Academy of Cosmetology and Aladdin Beauty College #1 were among them — but more often than not these schools had to count on only one graduate to repay his or her loans. Large institutions tended to have a less impressive showing. The University of Phoenix had almost 350,000 students enter repayment in 2009, with nearly $5 billion in outstanding loans. Its estimated repayment rate? Forty-four percent.

For those who work their way beyond its list of America’s top 50 colleges and universities, U.S. News & World Report also provides interesting data on the debt-load of students in the Class of 2009. The distinction of being the institution whose students graduated deepest in debt last year belongs to La Roche College in Pennsylvania, where 78 percent of students graduated with debt — to the tune of $69,494 on average. No other college comes close to La Roche in graduating students with such significant debt.

In second place is Oral Roberts University in Oklahoma, whose graduates left school with an average debt of $49,007, though 55 percent of its students managed to graduate with no debt at all. Elsewhere, 99 percent of Livingstone College students and 98 percent of Bennett College students graduated with debt. The debt-load of graduates from these two institutions, both in North Carolina, averaged about $35,000.

Predictably, few public institutions populate the list of schools that graduate students knee-deep in debt. (Exceptions include the University of North Dakota, Kentucky State University and the Maine Maritime Academy, where more than two-thirds of graduates left school with an average of about $35,000 in debt.) Private, nonprofit schools as well as for-profit schools dominate the list of students graduating with crushing debt.

Princeton University (photo by Quantockgoblin)

But there is some good news, too. A handful of institutions do an enviable job of getting their graduates out the door with little or no debt, and it turns out there’s a fairly strong correlation between highly ranked schools and schools whose graduates owe almost nothing. But a confounding factor, of course, is that more affluent students tend to attend these institutions in the first place, so it’s little wonder they can graduate almost debt-free.

Take Princeton University, for example: only 22 percent of students graduate in debt, and the average amount owed is a meager $5,667. This is partly a function of the fact that Princeton provides its students with very generous financial aid packages — made up entirely of grants rather than loans since 2001 — but it’s also a result of the fact that Princeton students are, on average, very affluent. Two out of five Princeton students in the Class of 2013 could afford to pay the full cost of attendance — $52,180 in 2010-11 — without any financial aid. But, to Princeton’s credit, it has become more socioeconomically diverse in the last decade. Back in 2001, three out of five Princeton students were affluent enough not to qualify for any financial aid.

Other schools that do a good job of graduating their students with minimal debt include the University of New Orleans, the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, Towson University (in Maryland), the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy (in New York) and Claremont McKenna College (in California). All of these but Claremont McKenna are public institutions, and all graduate more than two-thirds of their students debt-free. Of the 29 percent who owe money upon graduation from the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy, the average debt is only $6,416.

The higher education landscape in the U.S. is tremendously vast and varied. Students and parents alike would be well-advised to look not just as the flashy top 50 lists of best colleges and universities, but also to scrutinize the less sexy but equally or more important list of average student debt-load.

Recess round-up: August 17, 2010

A daily dose of education news around the nation – just in time for a little mid-day break!

Achievement gap: In “‘post-racial’ America, separate and unequal education is still the norm.” (The Atlantic)

Graduation rates: Only 47 percent of America’s black males graduate from high school on time, compared with 78 percent of their white male counterparts, according to a new report from the Schott Foundation for Public Education. (Education Week)

College rankings: Add Top Green Schools and What Will They Learn? to the recent rankings by Forbes and U.S. & World Report. Where are the rankings by actual students? (Sierra Magazine)

College freshmen: In an effort to ease the transition to college and improve retention rates, universities have ramped up orientation programs. (U.S. News & World Report and The Hechinger Report)

Early learners: About 4.5 million children are diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, or ADHD, yet nearly 1 million children may have been misdiagnosed — not because of behavior but because they’re the youngest in their kindergarten class. (USA Today)

Testing: Children do better on their exams when their teachers focus on learning, rather than on test results, according to a survey of recent research, published by the Institute of Education in London. (via UCLA/IDEA Newsroom)

Large-scale reform under way in Houston

Apollo 13 launches from Kennedy Space Center, April 11, 1970 (Photo by NASA)

It’s back to school today for students at four high schools and five middle schools in Houston. These students won’t only have an extra five days tacked on to their school year compared to their peers who start next Monday — they’ll also have a school day that lasts from 7:45 am to 4:15 pm Monday through Thursday, and from 7:45 am to 3:15 pm on Fridays.

Sounds like the winning formula of many charter schools, but these are all traditional public schools. They’ve just been targeted to undergo extensive reforms through Apollo 20, a new program of the Houston Independent School District. The program’s name was initially inspired by Apollo 13’s famous “Houston, we have a problem,” although Superintendent Terry Grier prefers to frame it as “Houston, we have an opportunity.”

The nine schools that have been flagged as “in need of improvement” (or that are rapidly heading in that direction) will adopt strategies that have been identified by Harvard economist Roland Fryer as working in successful urban and charter schools. These include extending the school day, driving instruction through routine data collection and providing an hour of one-on-two tutoring in math each day for sixth- and ninth-graders.

This project is one of the largest education reforms that any district is currently undertaking, according to Grier. But it’s going largely unnoticed at the national level. Perhaps that’s because it hasn’t ignited the same debate as have other reforms, like the opening of more charter schools or the development of new teacher-evaluation systems. The teachers’ union, which doesn’t have as strong a presence in Houston as it does in many large cities, hasn’t raised major objections, and no one else seems openly opposed to the reforms.

Or perhaps it’s because there are no results – good or bad – to discuss yet. Even the most preliminary results won’t be available for months, and a true sense of the program’s success or failure is years away.

Apollo 20, funded by federal grants and private and foundation donations, would seem to have many of the necessary ingredients for success: a dedicated faculty and administration, a solid research base and all the right buzzwords (e.g., “data,” “commitment,” “human capital”). And Houston is hopeful it’ll not only work but that it’ll be able to proceed as planned and expand to 11 elementary schools next year.

It’s an experiment worth watching. Many educators and policymakers have speculated over just how sustainable charter school practices are, and whether they can be transferred to traditional public schools. This is a chance to get some real answers.

Geoffrey Canada, founder of the Harlem Children’s Zone, knows all about the importance of experiments and whether they can be taken to scale. President Barack Obama wants to replicate the Harlem Children’s Zone in poor urban areas across the nation, and he’s allocated $210 million to the “Promise Neighborhoods Initiative” to do so.

Canada, for his part, has traveled around the country in hopes of inspiring educators to follow his lead. So far, “not one city has stepped up,” he said at a recent talk in Houston with Fryer. “America has decided that the only answer is to do a charter school and save two percent of the kids.”

While Canada believes the practices at Harlem Children’s Zone are replicable, a resistance to work outside the margins has prevented any large-scale reforms.

“You can do anything you want in education as long as you don’t change anything,” Canada said. “Heavens forbid we would ask people to work a little longer and a little harder.”

But that’s precisely what Houston has done. Every teacher employed at these nine schools had a “commitment talk” in which they were told of the new expectations. The district helped those unwilling or uninterested in taking on the new load to find jobs elsewhere by hosting a large job fair. Many elected to stay. Nine new principals were also hired, in a very selective process, as were over 200 math tutors.

And, in a less tangible move, the schools plan on creating a culture that charter schools currently have a monopoly on: They’ll be the “first ‘no-excuses’ public schools the country has ever seen,” Fryer said. Under this mentality, the schools will aim not only to have 100 percent of students performing at grade level, but also 100 percent graduating and attending college as well. The graduation rates of the four high schools in the Apollo 20 program are currently between 62 and 70 percent.

Still, as Fryer pointed, even if Apollo 20 had only 80 percent of the success that Canada’s organization has seen, the sheer scale of the project would mark it as a very successful reform for a public school district. That, though, is a tall order in itself.

“I don’t want to pretend it’s going to be easy,” Canada said. “But it is absolutely doable.”

Recess round-up: August 16, 2010

A daily dose of education news around the nation – just in time for a little mid-day break!

Achievement gap: Results on the latest New York State math and English tests indicate that the proficiency gap between minority and white students has returned to about the same level as when Mayor Bloomberg and Chancellor Klein began their terms in 2002. If you’re into numbers, take note: the gap between students in rich and poor schools increased from 15 percentage points in 2009 to 35 points this year. (The New York Times and The [New York] Daily News)

EduJobs: The $10 billion emergency funding to preserve teachers’ jobs comes too late for some. (The Atlanta-Journal Constitution)

For-profit education: Stocks drop, predictably, on the unimpressive loan-repayment rates of many for-profit institutions. (Bloomberg)

Rankings: Yale gets an “F” according to What will they learn?, a nonprofit website that rates 714 four-year colleges based on whether they require seven core subjects necessary to compete in the global marketplace and gain a well-rounded education. (The Christian Science Monitor)

Policy: Republican presidential aspirant Minnesota Gov. Tim Pawlenty heads west to a national forum on education. In June, Pawlenty appeared on The Daily Show and pitched the idea of offering more college courses online rather than by “boring professors” on campus. (The State Column)

Reform: The Michigan Department of Education will release today a list of the state’s worst performing schools. Schools that fail to make improvements could fall under control of a new state reform district in which teacher-union contracts could be tossed out and new staff brought in. This comes just after a study by Michigan State researchers suggests that consolidating schools would save the state millions. Stay tuned. (The Detroit News)

Teacher effectiveness: The Los Angeles teachers’ union president said he was organizing a “massive boycott” of the Los Angeles Times after the newspaper published on Sunday the first in a series of articles that will use student test scores to estimate the effectiveness of district teachers. (Los Angeles Times)

About the series: A grant from The Hechinger Report helped fund the work, though the Hechinger Institute did not participate in the analysis. The Los Angeles Times hired Richard Buddin, a senior economist and education researcher at RAND, as an independent contractor to conduct a “value-added” analysis of the data. Rand was not involved in his analysis.

You might also be interested in the recent report by Mathematica about error rates in value-added estimates.

Spending $10 billion to save jobs, sooner or later

The $26 billion bill signed by President Barack Obama earlier this week is intended to preserve jobs, and $10 billion of it is earmarked for saving teachers’ jobs — but how soon it will do so remains unclear. We wrote about the passage of this bill in an earlier post, and since then local education reporters around the country have been looking into what the $10 billion will pay for and when it will be spent.

In New York, the money may not come in time to restore programs and even curricula that have been cut. In Michigan, one state official wondered if strings will be attached to the money, which isn’t expected to hit the ground there till mid-fall. In Virginia, state officials said the money can be used “for pay, benefits and to provide educational services, but not for administrative expenses or support services.” In South Carolina, the money was welcomed, but it may not actually be spent until next year, when education budgets are likely to be tight once again. (The federal government has given states until September 2012 to spend the new money.)

And it seems that in a few places, the loss of teacher jobs was not as dire as predicted. The blog “This Week In Education” has been rounding up other stories; see here and here.

The U.S. Department of Education has just posted on its website guidance for states applying for the money, as well as the application itself, which includes a list of states and territories and how much money each is eligible for. The sums range from a high of $1.2 billion for California to a low of $17.5 million for Wyoming. American Samoa, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands and the U.S. Virgin Islands will receive a combined total of $50 million.

Texas has its own separate rules and application because the federal government wants to avoid a repeat of what happened with the Lone Star State last year: it diverted $3.2 billion in federal stimulus funds intended for education to balance its budget. If Texas wants the $830 million in new money for which it’s eligible, it will have to play by different rules.

Recess round-up: August 13, 2010

A daily dose of education-news around the nation – just in time for a little mid-day break!

Funding cliff: Some school officials in Illinois are skeptical of federal funding assistance. Even if money arrives, they say a one-time shot won’t help them keep staff. (The [Galesburg, Ill.] Register-Mail)

Charter schools: Tough going for a number of Chicago charters, half of which are running deficits. (Chicago News Cooperative via The New York Times)

Child development: Deciphering the teenage brain. (On The Brain via Harvard Medical School)

Education reform: Teacher quality as an imperative. (Slate via Financial Post)

And in Australia, where Parliamentary elections will take place on August 21, 2010, candidates propose taking money dedicated for disadvantaged schools to fund performance-bonus schemes and technology grants. (The Australian)

For-profit colleges: The U.S. Education department will release loan repayment rates for students at for-profit schools today, identifying institutions by name as part of an ongoing investigation into the for-profit college industry. (Reuters)

And when it comes to the recruiting practices of for-profit colleges, what regulations were in place? (Inside Higher Ed)

Jobs: There’s daily news about states’ decisions whether or not to accept one-time federal education funds after this week’s eduJobs bill was signed into law by President Barack Obama. The ed.gov website has a tidy table with projected allocations. (Business Week)

Student health: The number of college students afflicted with serious mental illnesses is rising. (Los Angeles Times)

Recess round-up: August 12, 2010

A daily dose of education news around the nation – just in time for a little mid-day break!

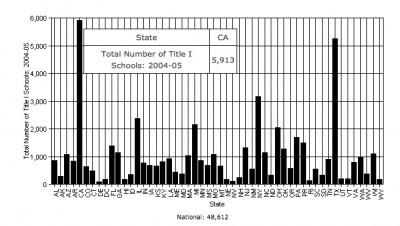

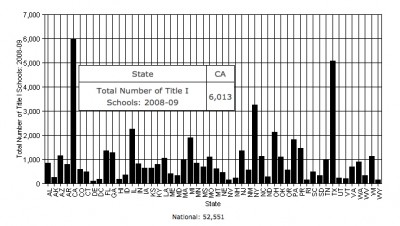

EdData: A new U.S. Department of Education website allows users to explore education data at the state level. This reporter compared the total number of schools, by state, receiving Title 1 funds in 2004-05 and 2008-09. (PromiseNeighborhoodsInstitute.org)

(Click on the images to enlarge them)

GreatSchools: Guess which large U.S. cities offer the top public schools, according to staff at GreatSchools.

(GreatSchools.com and WTVD-TV, Wake County, NC)

Funding: When should schools, which have until September 2012 to spend new federal funds, use the money? “This school semester. Now,” U.S. Education Secretary Arne Duncan told reporters at a Tuesday press-conference, after Congress approved the $10 billion measure to preserve teachers’ jobs. “We do not want people to wait until January or February. We want people to act, starting now.” (Tulsa World)

And speaking of Oklahoma, Former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush is stumping for Republican candidates while also highlighting the education initiatives of his eight years in office. (AP via The Miami Herald)

For-profits: Capella Education Co., which operates Capella University, announced it would try to buy back even more of its stock today. (Minneapolis St. Paul Business Journal)

And, in a column published on the Forbes magazine website yesterday, Sen. Tom Harkin (D-IA) summarizes his Senate Committee’s investigation into for-profit colleges and offers advice to prospective students. (Forbes.com)

Higher ed: An idea to end open-admissions and scale back remedial courses at Chicago City Colleges is under fire. (Community College Spotlight and Chicago Public Radio)

Safe schools: The U.S. Department of Education convened the first-ever federal summit on bullying. Or is it anti-bullying? No matter, sticks and stones may break my bones but names … (Christian Science Monitor and U.S. Department of Education)

Technology: In response to a blogger’s post on why educators need to embrace technology, a college student describes how Facebook was used to facilitate a discussion group. (EmergingEdTech.com)

Disproportionate share of turnaround money headed to high schools

In his education speech in Texas on August 9th, President Barack Obama told the nation, “We know what works. It’s just we’re not doing it.” The speech came as the U.S. Department of Education hands out $3.5 billion in turnaround grants to failing schools around the country, an outsized proportion of which will go to high schools. But when it comes to turning around high schools, educators admit that no one knows exactly what works.

The overrepresentation of high schools in the turnaround grant competition is partly on purpose. Department of Education officials say that secondary schools historically have been left out of allocations for disadvantaged schools despite research identifying thousands of so-called “dropout factories.” So a whole new category, called Tier II, was created in the grant competition just for high schools. (An explanation of the three types of schools eligible for turnaround money can be found here.)

Kelvyn Park High School in Chicago is one of the high schools eligible for a school improvement grant according to an Annenberg report (photo courtesy of Steven Kevil)

At least 43 percent of the Tier I and II schools that applied for school improvement grants – about 900 out of the 2,100 applicants – are high schools, according to my analysis of a report by Communities for Excellent Public Schools, which was led by the Annenberg Institute for School Reform. Nationwide, high schools make up only 24 percent of all schools.

The high percentage of high schools among the country’s worst schools might seem obvious. Once children reach high school, educational deficiencies have compounded over the years. Disadvantaged students who start out behind in kindergarten fall even further behind their more advantaged peers as each year passes.

Justin Cohen, president of the School Turnaround Group at Mass Insight Education, points out that high schools also tend to be singled out for turnaround more often because rates of violence and suspension are higher among older students.

The focus on high schools in the turnaround competition raises some questions, however. For one thing, experts say it’s harder to transform a high school from bad to good. As Tim Cawley, the managing director for the Academy for Urban School Leadership (AUSL), which is listed on the Education Department’s website as a model program, put it: “Nobody’s really cracked it.” AUSL focuses on elementary schools and applied for an Investing in Innovation grant to work on a model for high school turnarounds, but its application didn’t make the final cut last week.

In 2004, Johns Hopkins researchers identified 2,000 “dropout factories” around the country, and school districts have been trying to improve these high schools for the past decade to comply with the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001. For the most part, they’ve floundered (see what happened in Portland and Philadelphia for examples).

The relatively few successes are evidence that turning around high schools is a delicate and very expensive project. Locke High School in Los Angeles, which was taken over by Green Dot, a charter school operator, is a positive example that the U.S. Department of Education also cites. But the high costs of the transformation have raised eyebrows among educators, who wonder how they can replicate a $15 million effort with the $6 million or less allotted for each school in the federal grant competition.

In New York City, education reforms seem to have been more effective at the high school level, where graduation rates have risen over the past eight years, than at the middle school or elementary levels, where results on state tests arguably show little improvement. Yet New York City’s high school reforms were also funded largely by private dollars and there were many flaws; the school system is still working out all the kinks.

And Hempstead High School, on Long Island – where I spent about four years in and out of the school as I was researching a book about gangs – is an example of how difficult it is to sustain improvements. When I arrived, the school’s problems ranged from low graduation rates to kids being murdered on or near school grounds. The turnaround was an excruciating process. The district finally hired a strong principal after years of churning leadership and tried other innovations like splitting the school into smaller academies. Over the four years, the graduation rate shot up, to 65 percent from 40 percent. But the gains didn’t last: The principal left last year, violence escalated and the graduation rate slipped.

Joseph Harris, director of the National High School Center at the American Institutes for Research, agrees that high schools are particularly tricky in the already tricky business of school turnarounds.

“If you look historically, high schools look a lot more like they did 50 years ago than elementary schools,” he says. “High schools are big, bulky and they’re old-fashioned, and therefore getting them to do things totally differently to meet the needs of all students is a challenge.”

The problems at struggling high schools often include students who are years behind their peers. “It’s the high school’s problem, but it’s not the high school’s fault alone,” says Justin Cohen, of Mass Insight Education.

So why not focus on elementary and middle schools, where the work is potentially easier – the preferred strategy of many charter school networks? Elementary and middle schools, not to mention early childhood, are also arguably where the problems start. But Harris says that despite the difficulties, high school reform shouldn’t be avoided.

“It’s important to invest early to avoid the problems in high school, but you can’t ignore one or the other,” says Harris. “If high schools were easy to [fix], people would have done it.”

Almost all of the states that applied for school improvement grants have now been awarded the funds. The next step in the process, already under way in many states, is for state departments of education to distribute the funds on a competitive basis to local districts. The U.S. Department of Education has published state applications, including lists of all eligible schools, here.