New Brookings report from scholars in favor of value-added measures

“‘Where are the academics who are in favor of value-added?’ Here they are, with persuasive reasoning.”

So concludes the press release that today announced a new Brookings report, “Evaluating Teachers: The Important Role of Value-Added.” The report was co-authored by Steve Glazerman (Mathematica Policy Research), Susanna Loeb (Stanford), Dan Goldhaber (University of Washington-Bothell), Doug Staiger (Dartmouth), Stephen Raudenbush (University of Chicago) and Russ Whitehurst (Brookings).

The report can be seen in some ways as a direct reply to the EPI brief, “Problems with the Use of Student Test Scores to Evaluate Teachers,” released in August. The EPI brief was co-authored by an equally distinguished set of scholars, including Linda Darling-Hammond, Helen Ladd , Diane Ravitch, Richard Rothstein and Lorrie Shepard.

The Brookings paper also addresses recent reports on value-added measures from the Educational Testing Service, the Institute of Education Sciences, the National Academies and RAND. The authors acknowledge some common ground with what others have argued — no serious scholar has said that value-added measures should be the sole factor in teacher evaluations, and few favor publishing individual teachers’ value-added scores — but they also highlight their disagreements:

“There are three problems with these reports. First, they often set up an impossible test that is not the objective of any specific teacher evaluation system, such as using a single year of test score growth to produce a rank ordered list of teachers for a high stakes decision such as tenure. Any practical application of value-added measures should make use of confidence intervals in order to avoid false precision, and should include multiple years of value-added data in combination with other sources of information to increase reliability and validity. Second, they often ignore the fact that all decision-making systems have classification error. The goal is to minimize the most costly classification mistakes, not eliminate all of them. Third, they focus too much on one type of classification error, the type that negatively affects the interests of individual teachers.”

On this last point, the Brookings authors explain that “the interests of students and the interests of teachers in classification errors are not always congruent, and … a system that generates a fairly high rate of false negatives could still produce better outcomes for students by raising the overall quality of the teacher workforce.”

The authors readily acknowledge that value-added measures aren’t perfect — but they don’t take that to mean value-added measures should be thrown out: “It is not a perfect system of measurement, but it can complement observational measures, parent feedback, and personal reflections on teaching far better than any available alternative. It can be used to help guide resources to where they are needed most, to identify teachers’ strengths and weaknesses, and to put a spotlight on the critical role of teachers in learning.”

The key questions, then, are when and how value-added data are used. Whether these data should be used in teacher evaluations, the authors argue, is clearer (i.e., yes) than whether they have a place in personnel decisions (maybe).

These lines, from the conclusion, provide a useful summary of the Brookings paper: “When teacher evaluation that incorporates value-added data is compared against an abstract ideal, it can easily be found wanting in that it provides only a fuzzy signal. But when it is compared to performance assessment in other fields or to evaluations of teachers based on other sources of information, it looks respectable and appears to provide the best signal we’ve got. Teachers differ dramatically in their performance, with large consequences for students. Staffing policies that ignore this lose one of the strongest levers for lifting the performance of schools and students. That is why there is great interest in establishing teacher evaluation systems that meaningfully differentiate performance. Teaching is a complex task and value-added captures only a portion of the impact of differences in teacher effectiveness. Thus high stakes decisions based on value-added measures of teacher performance will be imperfect. We do not advocate using value-added measures alone when making decisions about hiring, firing, tenure, compensation, placement, or developing teachers, but surely value-added information ought to be in the mix given the empirical evidence that it predicts more about what students will learn from the teachers to which they are assigned than any other source of information.”

For in-depth materials on the timely topic of evaluating teachers – including links to important reports and news coverage on value-added measures – see our relevant “Go Deep” section.

Turning teacher education “upside down”?

“Bold” is a favorite word among education reformers everywhere, and supporters of a new plan put forward by the National Council for the Accreditation of Teacher Education (NCATE) to overhaul teacher education are no different. James Cibulka, president of NCATE, is quoted in the Wall Street Journal today saying that teacher education is due for the “large, bold, systemic changes” suggested in his organization’s report. Among them: requiring that teachers spend more time practicing how to teach before they’re let loose to run their own classrooms, and that higher education and school districts work together more closely in choosing who can become a teacher.

It’s now conventional wisdom that teacher quality is the most important factor under a school’s control in influencing student achievement. It’s also widely accepted that teacher-education programs in general are not doing a great job of selecting and preparing teachers. So there’s broad consensus that teacher education needs an overhaul.

The report looks to medical schools as a model, which isn’t a completely new idea:

“The current practice of supervision of student teachers in schools now is typically assigned to a teacher as extra work, usually with no training, support, or changes in schedule. Schools need to adopt a new staffing model patterned after medical preparation, in which teachers, mentors and coaches, and teacher interns and residents work together as part of teams,” the report says.

It also calls for stricter oversight of ed-school accreditation and more accountability to ensure that teacher training actually addresses school district needs.

Much of the initial response to NCATE’s report has been positive. Here’s what Randi Weingarten, president of the American Federation of Teachers and a member of the panel that wrote the report, said: “Rather than engage in a false choice about whether to continue the status quo or eliminate college-based teacher education programs altogether, NCATE wisely has focused on what is best for students.”

Education Secretary Arne Duncan, who spoke at a gathering for the report’s release, was also upbeat, as quoted by the Atlanta Journal-Constitution: “It is time to start holding teacher preparation programs far more accountable for the impact of their graduates on student learning and achievement. It is time to make accountability much more rigorous, outcome based.”

But not everyone thinks the report’s recommendations are all that new — or bold. Kate Walsh, president of the National Council on Teacher Quality, told the Denver Post that she was “trying to figure out what is different with this report.” Rick Hess, of the American Enterprise Institute, says the suggestions in the report don’t go far enough: “After all, the ‘normal school’ and programs of teacher preparation are 19th century innovations; isn’t it possible that a ‘radical’ 21st century rethinking might not want to presuppose that we rely on that machinery?” he wrote. Hess had hoped to see more about training for “virtual instructors, online tutors, or Citizens Schools-style ‘citizen-teachers’ ” and wonders where all the teacher-mentors called for in the report will come from.

California, Colorado, Louisiana, Maryland, New York, Ohio, Oregon and Tennessee have agreed to implement the report’s recommendations. We’ll be watching to see if teacher education in those states stays on its feet or if it’s flipped upside down after all.

Will the Tea Party try to do away with the U.S. Department of Education?

On the campaign trail, it became “cool” among Tea Partiers to support the elimination of the federal Department of Education. The proposals revive an old Republican idea that lost steam last time it was introduced, once winning candidates faced the reality of day-to-day lawmaking. Whether the new crop of Republicans will actually attempt to do away with the department is still unclear.

In a conversation on Errol Smith’s BAM! Radio show, Andrew Kelly of the American Enterprise Institute suggested that whether or not the new Republicans in Congress push the issue isn’t that important. What matters is that their stance symbolizes a general attitude about the federal government’s role in education that could complicate President Obama’s education agenda. They’re likely to block any efforts to renew big federal education efforts like Race to the Top, for example, as we’ve suggested here previously.

New Republican opposition could scuttle compromise on reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act – or not. The real action, however, is probably going to be in the states, where Republicans grabbed large majorities in many legislatures and where the economic crisis has crippled district budgets, even as Race to the Top winners are beginning to implement federally driven education reforms and a majority of states are overhauling standards.

When the best and brightest aren’t really the best (or brightest)

It’s no secret that students in the U.S. stack up poorly against their international peers on math assessments. But even our best and brightest don’t match up with the highest achievers internationally, according to a new comparison.

In the Winter 2011 volume of Education Next, “Teaching Math to the Talented” — by Eric Hanushek, Paul Peterson and Ludger Woessmann — details how a considerably lower percentage of American students in the high school Class of 2009 were deemed “highly accomplished” in math than were students from other countries. In fact, 30 out of the 56 countries in the analysis had a larger percentage of students scoring at the advanced level than the United States.

Although much of the discourse around achievement centers on those who are currently underachieving, the report’s authors argue that this focus isn’t enough if we want to be a competitive nation. “Both federal funding and the accountability elements of No Child Left Behind (NCLB) have stressed the importance of bringing every student up to a minimum level of proficiency,” the authors say. “As great as this need may be, there is no less need to lift more students, no matter their socioeconomic background, to high levels of educational accomplishment.”

Even Massachusetts, the state with the greatest percentage of high-achieving math students, was still outperformed by students in 14 different countries. And in Mississippi, the lowest-ranked state, only 1.3 percent of students were highly accomplished in math — a result that 42 other countries surpassed.

So why are we falling so far behind even at the high end of the spectrum? It’s not that NCLB takes the focus off high-achieving students — an explanation the study’s authors consider but then dismiss. They don’t offer a different explanation.

The Hechinger Report’s Go Deep section on Math does look at an alternative explanation for the nation’s lower math achievement levels across the board: They might be the result of how we teach math.

In U.S. classrooms, teachers tend to cover lots of material superficially at the expense of having students master fewer skills that they can then build on, as teachers in other countries do. Or, as William Schmidt, an expert on math education at Michigan State University, put it: U.S. math curricula are typically “a mile wide and an inch deep.”

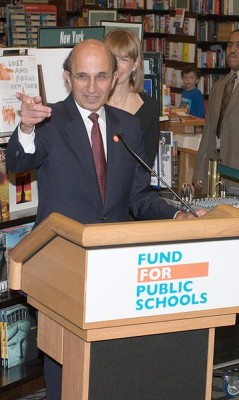

Sarah Garland talks to PBS about Joel Klein’s departure

In the wake of Joel Klein’s resignation as head of the nation’s largest school system, Sarah Garland of The Hechinger Report spoke with Gwen Ifill of the PBS NewsHour on November 10th. Garland discussed the significance of Klein’s departure and what lies ahead for New York City, as well as what the research says about Klein’s record on graduation rates, test scores and the push for smaller schools.

Joel Klein’s legacy of reform, rage and rising graduation rates

Joel Klein, one of the longest-serving chancellors of the New York City public schools, is stepping down. Klein was appointed in 2002, when the state legislature gave Mayor Michael Bloomberg control of the city’s school system. He oversaw a sweeping overhaul of the city’s public schools that was both lauded and condemned. Supporters say his reforms led to significant increases in student achievement and the city’s graduation rate, but his many critics say he was often dismissive of community concerns and that some reforms were more harmful than helpful.

Klein’s most significant moves include reshaping the school’s central bureaucracy (twice), giving more responsibility and authority to principals in exchange for more accountability, opening more charter schools, giving large raises to teachers, and reformulating how funding is allocated to schools (by attaching money to students based on attributes like their low-income or special education status).

He was aggressive in closing schools based on their standardized-test performance, a move that enraged many parents. The closures were also condemned by some researchers because the new schools that opened in their place often did not serve as many high-needs student. Yet at the same time, graduation rates rose to 63 percent, up from 47 percent, according to state calculations.

Of Klein’s replacement, Cathleen Black, former publisher of USA Today, Bloomberg was quoted by Gotham Schools as saying: “I know the first thing she’ll want to do is reach out to parents, teachers, principals and administrators to get the benefit of their wisdom.”

Although Klein generally enjoyed support from the city’s editorial boards (Interestingly, he’s going on to take a job at News Corps, owner of the New York Post, one of this biggest fans), he weathered a lot of rocky moments, from school-bus routing scandals to a major drop in the city’s test scores after they were graded more strictly this year. As a former trial lawyer, he defended his policies rigorously, but his critics often accused him of being tone-deaf.

The timing is interesting: Tomorrow, big-name researchers from around the country are convening in New York City to critique Klein’s reforms. The presentations will examine things like his department’s relationship with parents and the community and his efforts to delegate more authority to individual schools. Many of the papers that will be presented seem sympathetic to the ideas behind Klein’s reforms, but they also find flaws in how some reforms were implemented and sold to the public. Klein is scheduled to respond to the findings at the end of the day.

I covered Klein for a year in 2006 as a reporter for the now-defunct New York Sun. As I was covering the school system as a newspaper reporter, it sometimes seemed as if the education department’s reforms could be spontaneous –- the decision to dismantle a system of regional offices, which the city had spent four years creating, in favor of a whole new bureaucratic design, seemed to happen without warning, for example.

I recently wrote a story for Washington Monthly that looked back at Klein’s secondary school reforms. As I interviewed city officials about their efforts, I discovered some method to what occasionally came across as madness, to put it glibly. That is, the vision wasn’t always clear to those of us covering it, or to the people it affected –- teachers, parents, students –- but that’s not to say there wasn’t a road-map that the department was following. It’s also not to say that Klein got it right every time, as the folks I talked to acknowledged.

The merits of their reforms can be debated, but there’s no question that Klein, and Bloomberg, made the city an important player in the education reform debate nationally. In many ways, New York City has been a Petri dish for some of the big education ideas that are now being replicated across the country, from transforming how teachers are compensated to the aggressive school-turnaround models that the federal government is promoting.

Stay tuned to The Hechinger Report – we’ll be rounding up the coverage (for ongoing reports from the press conference today, be sure to check out Gotham Schools), listening to what Klein has to say tomorrow and also adding more in-depth analysis about what this means for the education reform movement nationally.

Are age and experience overrated when it comes to leadership?

Studies show that children who can delay gratification -- by resisting marshmallows -- are more successful as adults than those who can't (courtesy of Smith609)

Age and experience: How much do they matter when it comes to positions of power and authority?

Fifty years ago today, the United States elected its youngest leader to date — John F. Kennedy was just 43 when he edged out Richard Nixon in the 1960 presidential election. The U.S. Constitution, of course, sets minimum-age requirements for the House (25 years old), Senate (30) and presidency (35). Many other countries set the bar somewhat higher. In Italy, for instance, a person must be at least 50 to become president.

In education, there aren’t any minimum-age requirements for principals or superintendents (at least, not to my knowledge), and in this day and age it’s no longer odd to find young people at the helm.

Consider Shonda Davis. Last month she was appointed principal of Barringer High School in Newark, N.J., a troubled high school of 1,300 students whose leader, Ron Lustig, quit after one month on the job. Davis is 27.

And then there’s Zeke Vanderhoek, who founded Manhattan GMAT — a high-end test-prep company that has done very well since its founding in 2001 — in his early 20s and who is now, at 34, principal of The Equity Project (TEP) Charter School that he founded three years ago. The school, which grabbed headlines for its business model of paying teachers minimum salaries of $125,000 each, opened its doors in September 2009.

Michelle Rhee, former Chancellor of the D.C. Public Schools, was appointed to that position by Mayor Adrian Fenty when she was 37. Rhee had three years of teaching experience.

This isn’t an entirely new trend — back in 1964 Ted Sizer became dean of the Harvard University Graduate School of Education at age 31 — but it seems to be accelerating.

It is against this backdrop that I participated in a recent discussion — entitled “Manage Millennials to Get Their Best Work” — on the BAM! Radio Network, with Jeanne Meister (an expert on workplace learning) and Holly Elissa Bruno (our host).

Jeanne noted that “millennials” — whom she defines as those born between 1977 and 1997 — constitute about 38 percent of our current workforce. She also noted that millennials will be a majority of the nation’s workforce by 2020, at which point we’ll have five generations working side by side.

Are millennials different than their predecessors? If so, in what ways? Jeanne argues that millennials have a different set of expectations than previous generations — and that, among other things, they’re much more driven and want to be developed in personal, social ways (such as through mentors or “coaches” at work). Also, they have come of age communicating online and prefer texting or Instant-Messaging over the more traditional, old-school form of email. (Who would have thought that we’d already be describing email as “old-school” by 2010?)

In a May 2010 Harvard Business Review article, Jeanne and her co-author Karie Willyerd report the following from their survey of 2,200 professionals in a number of fields: “Millennials view work as a key part of life, not a separate activity that needs to be ‘balanced’ by it. For that reason, they place a strong emphasis on finding work that’s personally fulfilling. They want work to afford them the opportunity to make new friends, learn new skills, and connect to a larger purpose. That sense of purpose is a key factor in their job satisfaction; according to our research, they’re the most socially conscious generation since the 1960s.”

They also point out, as Jeanne did on the radio show, that millennials want constant and immediate feedback on how they’re doing at work. But this isn’t necessarily something their supervisors are accustomed to providing, of course. Jeanne and her co-author suggest three types of mentoring that can work for the “mobile, collaborative lifestyle and need for immediacy” that characterize millennials: reverse mentoring, group mentoring and anonymous mentoring. (To find out the specifics on these, read the original HBR article.)

Jeanne described “anonymous mentoring” on the radio show as similar in approach to Match.com. A person can identify areas he or she wants to grow and develop in, and then an online platform – making use of “micro-feedback assessment” – allows for peers or mentors to offer anonymous feedback, Twitter-style (max. 400 characters). The beauty of such feedback, Jeanne said, is that it’s succinct and immediate — two things millennials prize.

I ended up playing something of the skeptic in the conversation, arguing that just because millennials want certain things doesn’t mean they should always get them. Yes, younger people tend to like workplaces that are less hierarchical and less formal — the Googleplex, complete with free laundry rooms, swimming pools and beach-volleyball courts, is perhaps this generation’s ideal — but there is also some value in hierarchy and formality. So, too, is there value in paying one’s dues and working one’s way up the corporate ladder rather than expecting to be CEO by 30.

I very much believe that learning to delay gratification is an important life skill. Parents, and teachers, need to be in the business of teaching young people that we don’t always get what we want right away (or ever!). Self-control and persistence are values we should instill in children from birth, not least so that people don’t immediately give up when something goes awry. It’s no secret that many — most? — inventions are the result of hundreds, or thousands, of failed attempts. Success is sometimes the result of a lifetime of failure, which is a lesson quitters never learn.

How a student’s college major shapes experience in classroom and beyond

Picking a major isn’t easy for many college students. For some, the decision is an important step toward realizing a lifelong dream; for others, it’s nothing but stress and uncertainty until the deadline to declare arrives, and then the tiniest of factors might tip the scales in favor of one concentration over others.

We all know that a student’s major heavily influences what courses he or she takes, but less well-known is how a student’s major also shapes the types of work done within, and beyond, these courses. A new report released by the National Survey of Student Engagement today, “Major Differences: Examining Student Engagement by Field of Study – Annual Results 2010,” reveals just how many differences there can be from major to major outside of the curriculum.

The survey, completed by 362,000 first-year students and seniors at 564 colleges across the country, yielded some “promising” and some “disappointing” findings, according to the report.

Among the positive findings were the facts that “three out of four seniors in nursing and physical education did service-learning as part of their coursework, well above the overall average of 49 percent” and that students majoring in most subjects “used quantitative information in their courses in several ways.”

There was also some unsurprising news — that English majors write more papers than their peers and that biology majors are more likely to do research with faculty than other students.

But despite all the focus on majors in this report, when it comes to the disappointing news, students’ specializations didn’t receive much focus.

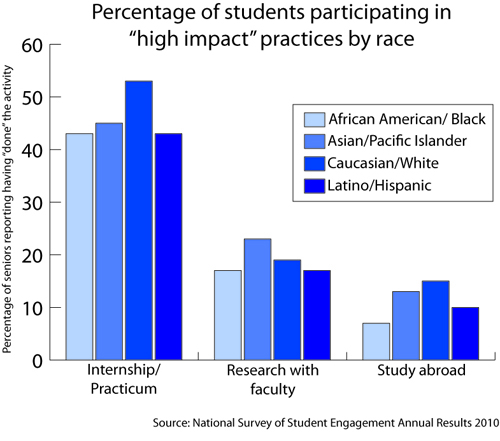

Across all majors, African-American and Latino students were less likely to study abroad, do research with faculty or have internships than their white and Asian peers. And, although not highlighted in the report, this year’s survey also showed that first-generation college students were also less likely to do these things.

Ensuring equal access to college has long been a goal in higher education, but this report joins other data that demonstrate something Estela Mara Bensimon at the Center for Urban Education has called “nuanced inequalities” between white and minority students, such as taking on leadership roles, studying abroad and making it on the dean’s list.

“One of the most critical challenges facing institutions of higher education in the twenty-first century is the need to be more accountable for producing equitable educational outcomes for students of color,” Bensimon wrote in an article in Liberal Education. “Although access to higher education has increased significantly over the past two decades, it has not translated into equitable educational outcomes.”

Will Republicans reduce the federal ‘footprint’ in education?

Is it really a new day for education in the U.S.? There is no dearth of opinions — or questions — about what could change now that Republicans have taken control of the House of Representatives in Tuesday’s elections. One conclusion is generally shared, though: Federal money will be scarce.

The economy — and not education — took center stage in candidates’ campaigns and voters’ minds, but the two are of course intertwined, Patrick Riccards notes on his Eduflack blog: “…those thinking there are new pots of money for additional rounds of Race to the Top, i3, edujobs, or other such programs are likely to be severely disappointed. We’re back to doing more with less.”

Hear, hear, says Mike Petrilli of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute. “A new era of budget austerity is upon us and it won’t be popular at all … states and school districts are flat-out broke. Just about all of the typical budget tricks (cashing in rainy-day funds, refinancing debt, looking for one-time windfalls) have already been used. And a GOP-controlled House is very unlikely to come to the rescue with another bailout.”

Riccards said in an interview with The Hechinger Report that one result of an inevitable shift in priorities could be a faster reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (known as NCLB under President George W. Bush), in part because incoming Speaker of the House John Boehner (R-Ohio) was among the lawmakers who worked with Bush on crafting the law.

“Obama realizes education needs a quick win,” Riccards said.

And Republicans and Democrats have been known to meet in the middle on education, writes Valerie Strauss on the “Answer Sheet” blog of The Washington Post.

Because Republicans and “Obama Democrats” meet in the middle on key education issues, Strauss notes, “there is some thought, including in the White House, that enough common ground can be found to reauthorize No Child Left Behind at some point in the next two years. Obama may be willing to give up a lot to get a legislative success in his last two years.”

Rick Hess of the American Enterprise Institute expects to see some dialing back of a federal role in education as the new Republican House members attempt to cut back on record-level government spending. “Even sensible arguments about ESEA reauthorization and Race to the Top … will fall on deaf ears,” Hess predicted in an interview. “They will have very little interest in new spending, or in anything that even looks like new spending.”

On the higher-education front, InsideHigherEd reports there will be “no curveballs.”

“In the House, Republicans are expected to push for budget cuts and greater oversight of all of higher education, not just for-profit colleges. In the Senate, Senator Tom Harkin (D-Iowa) will continue the Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee’s examination of for-profit colleges into next year,” writes Jennifer Epstein.

Harkin and Sen. Richard Durbin (D-Ill.) have said they plan to introduce legislation in 2011 targeting perceived waste, fraud and abuse in for-profit higher education.

Education Week reports that Republican control of the House “will almost certainly mean an end to emergency education aid to states … and will heighten pressure for a more limited role in K-12 policy.”

The election and education: What will change?

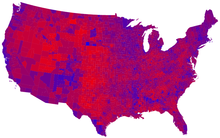

The short answer to that question might be, not much. The Obama administration has embraced education reforms that are also favored by many conservatives, most particularly charter schools and overhauling how teachers are evaluated and paid. So if Republicans sweep the House today and grab the Senate, too, the direction that education policy has been headed for the past two years may not shift dramatically. In fact, it could become more of a priority as one issue where the Obama administration and Republicans can find some common ground.

That said, others have argued that Obama’s education reform agenda may not be so safe. For one thing, points out Andrew Kelly (writing on the Rick Hess Straight Up blog), as many as 28 Republican candidates have advocated eliminating the U.S. Department of Education in their campaigns. If elected — and Kelly thinks many of the 28 will be — these folks are probably not going to be allies as the Obama administration starts the process of reauthorizing the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (known as NCLB under President George W. Bush) next year. It’s also unlikely they’ll jump to support a second Race to the Top contest, to say the least.

On the local level — where most of the education policy sausage gets made — there are also likely to be many new faces who could transform the education policy landscape. Many governors are up for reelection in states that won the Race to the Top competition. The governor of Tennessee, a first-round winner, extracted promises from all of the candidates running to replace him to support the state’s education reforms, but that’s certainly not the case everywhere.

There are also education issues that were already in a precarious position before election day. Early-education advocates have been wringing their hands for months over the uncertain fate of the Early Education Challenge Fund, which is currently stalled in Congress. Senators have passed a version of the bill, mostly with Democratic support, and are now waiting on the House. With the strong possibility of a Republican-controlled House on the horizon, prospects for the measure don’t look great.

While support for early education extends across partisan lines — just look at Oklahoma, one of the reddest states on the map, and its universal pre-Kindergarten program — any proposal to increase government spending will face a tough battle no matter what happens after the election. The Obama administration has also warned that Head Start could be endangered by big Republican victories, although Republicans say that’s not true.

Education-wise, some of the most interesting races to watch this evening will be Democratic Senator Michael Bennet’s in Colorado (as former superintendent of the Denver public schools, he’s been an important education ally in the Senate for the Obama administration), along with the gubernatorial contests in Florida and Ohio, where results could mean significant shifts in education policy on the state level. For the New York races, Gotham Schools has an election voter’s guide.

It will also be interesting to watch what happens in Congressional committees and subcommittees. If Republicans take the House, Rep. John Kline may end up as the head of the House Education and Labor committee, replacing Rep. George Miller. Also important is the subcommittee on education appropriations; there, the ranking Republican, Todd Tiahrt, is currently running for the Senate. If Republicans turn enough Democrats out in the Senate, control of the education committee there could go to Sen. Mike Enzi, which may be a cause for celebration among for-profit universities.