Making a difference in a new role

Editor’s Note: Today, Education Sector Board Chair Macke Raymond announced that Richard Lee Colvin will join Education Sector as its executive director.

For the past eight years, I’ve had the great fortune to lead the Hechinger Institute on Education and the Media at Teachers College, Columbia University where, most recently, we created The Hechinger Report, which is a nonprofit, nonpartisan source of in-depth reporting on education. We’ve had good support from foundations and have collaborated with many fine news organizations to increase the supply of such coverage. The Hechinger Report will continue on its current course; a number of ambitious projects are in the works. It’s been an exhilarating, exhausting and highly rewarding time, one that I will value for the rest of my life. In that endeavor, I’ve had the honor of working with talented and committed colleagues who believe in good journalism and in the power of education to change lives.

I know that power personally. Neither of my parents had the chance to go to college, though they educated themselves along the way and achieved great success. Perhaps their biggest success was that they insisted on their four sons going to college and told us that we had to earn scholarships because they wouldn’t be able to afford the tuition. That’s what we did, and all of us earned degrees, got good jobs, formed families and sent our own children to college. Education has a multiplier effect like that: Educate one generation, and that generation will make sure its children are educated. The nation will thrive as a result, reaping the rewards of invention, creativity and productivity.

Since its founding by Andy Rotherham and Tom Toch, Education Sector has used the power of good ideas communicated clearly to help improve the odds that all Americans will have the opportunity to gain a good education. The foundation for their work has always been evidence, not ideology. And they have become an important asset in this quest.

This is an exciting time to be working in education policy. The next 10 years will bring greater international economic competition and we as a nation must find ways to educate far more of our young people far better than we’ve done in the past. Education Sector will be a leader in this effort by bringing forth innovative solutions and advocating for them with policy makers. I am thrilled to have the opportunity to lead the organization as we extend our work into new areas and grow in reach and influence.

Quality Counts 2011: The Great Recession’s impact on public education

Today, Education Week released its annual Quality Counts report, a treasure trove of articles, charts and graphics that in 2011 focus on how the Great Recession has affected public education in the U.S.

The report issues letter grades to all 50 states and Washington, D.C. based on multiple metrics, including K-12 Achievement, School Finance, Transitions and Alignment and Chance-for-Success (the last of which “captures the importance of education in a person’s lifetime from cradle to career,” according to the report).

The nation as a whole earned a C, while Maryland won top honors — as it did in 2009 and 2010 — with a B+. Not far behind were Massachusetts and New York, both of which earned Bs. At the very bottom of the list, each earning a D+, were South Dakota, Washington, D.C. and Nebraska.

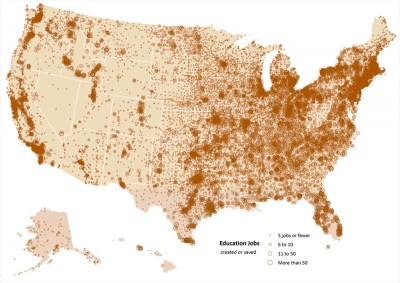

With regard to the recession, the report’s authors note that 52 percent of all jobs saved or created by the American Revcovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) — also known as the federal stimulus — were in the field of education. The map above pinpoints the locations of these 337,000 education-related jobs.

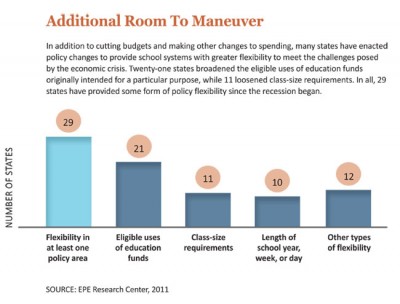

Among the more interesting findings of the report are those related to how states have responded to their budget crises:

- “Since the recession began, 29 states have enacted policies that offer local school systems some form of flexibility to meet the challenges posed by the economic crisis.

- “Twenty-one states have broadened the eligible uses of education funds originally intended for a particular purpose. In 11 states, class-size requirements have been loosened; 10 states have offered the option of modifying the length of the school year, week, or day as a way to cut costs.

- “Only three states have waived protections on K-12 education funding since the start of the recession.”

In an article entitled “Personnel Costs Prove Tough to Contain,” Sean Cavanagh details pension shortfalls plaguing states in general — and especially California, which has unfunded liability to the tune of $40 billion. Cavanagh notes that “California’s entire budget for fiscal 2011, by comparison, is $87.5 billion.”

In the same piece, Cavanagh looks at a performance-pay plan in Colorado Springs that hasn’t received much media attention, at least compared to other performance-pay schemes in places like Denver and Washington, D.C.

Colorado’s Harrison School District Two, which serves 11,000 students, introduced the plan — which “links teachers’ salaries to their ability to raise student performance, classroom observations, and other factors” — last fall.

Cavanagh reports, “The Harrison district, which has an annual general-fund budget of $80 million, gave about 75 percent of its teachers an initial salary boost at the beginning of the school year when they were placed on the new performance scale for the first time. The district estimates that only about 20 percent of teachers will be given raises based on their performance this academic year, and that the remaining 80 percent will have their salaries frozen, though those numbers could change, Superintendent Mike Miles says.

“The Harrison district does not give automatic pay increases, or stipends for advanced degrees. It also does not provide extra pay for teachers’ service as mentors, and it saves considerable money by not paying educators extra to serve as department chairs or team leaders; the district regards those duties as professional responsibilities, Miles says.

“The district spent about $1.2 million to create the performance-pay system, with $800,000 coming from a foundation grant, Miles says. But after that initial expense,he believes the system will be revenue-neutral. He also says other districts, including larger ones, could replicate pay models like Harrison’s without incurring new costs, though he thinks the primary motivation for such plans is to recruit new teaching talent and raise student achievement.”

This sounds like an experiment well worth watching. And in the coming weeks, be on the lookout for a new “Go Deep” section from The Hechinger Report devoted entirely to the issue of teacher compensation.

Congratulations to Cavanagh and the entire Ed Week team on a first-rate report!

Teachers-in-training deemed ‘highly qualified’ by Congress

Congress was busy the week before Christmas, capping off a legislative session that saw the most laws passed since the 1960s. In the final days of the lame-duck Congress, the Senate and House passed items ranging from the high-profile James Zadroga 9/11 Health and Compensation Act and new food-safety legislation to a “continuing resolution” that funds the government until March.

Buried in the continuing resolution, passed on Dec. 22, was language that explicitly extends the title of “highly qualified teacher” to those still in training.

The term was first introduced in legislation in No Child Left Behind. The 2001 Act required that parents be alerted if their child’s teacher didn’t have a college degree in the subject area taught, state certification or competence in basic skills (or the subject area). Teachers who didn’t hit these benchmarks – and who were consequently deemed not highly qualified – were supposed to be spread somewhat evenly throughout the school system.

But for the past nine years, individuals taking alternate paths to the classroom — through, for instance, Teach For America or The New Teacher Project — have counted as highly qualified teachers. In most cases, these teachers-in-training receive a few weeks of preparation over the summer and take graduate-level classes while teaching, ultimately earning certification after a year or two.

In September, a federal court ruled that these individuals can’t legally be considered highly qualified. But the continuing resolution directly contradicts that decision, and the court’s ruling has been appealed.

There’s an argument to be made that looking at the definition of highly qualified teachers is the wrong conversation to be having because it focuses on inputs, not outputs, unlike attempts around the country to define a “highly effective teacher.”

Yet many will also argue that, at least in some ways, inputs and outputs are linked – and that five weeks of training simply isn’t enough of an input to guarantee a quality output. Of course, it all depends on whom you ask. Teach For America points to research that indicates its members do as well or better than other first-year teachers and sometimes even veteran teachers. Other research has found that alternatively certified teachers are not as good as their traditionally trained peers.

Many bloggers, including at least one former TFA member and current teacher, have criticized Congress for this action. Yet the office of Sen. Tom Harkin (D-Iowa), chairman of the Senate’s education committee, released a statement on Dec. 20 describing the decision as a “broad, bipartisan agreement,” adding that the court’s verdict “could cause significant disruptions in schools across the country and have a negative impact.”

Harkin’s office also said the issue will be considered as part of the reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) — known in its most recent incarnation as NCLB — next year.

How will suburban schools handle the new influx of immigrants?

In the next 20 years, the schools in need of the most help may not be the schools in inner cities like Newark or Detroit. Instead, they may be in far-flung suburbs and exurbs, where immigrants are flocking in increasing numbers, according to new projections from the U.S. Census Bureau.

We’ve known for a while that the new immigrant frontier was in the suburbs, but are education officials and reformers paying attention? Hispanics are the fastest growing suburban group, and, as the New York Times pointed out today, “Graduation rates for blacks and Hispanics — the overwhelming majority of all immigrants in the United States — are far below those for whites. The trend line therefore suggests that the country will be facing a growing shortage of educated Americans as global competition intensifies, particularly as other countries’ graduation levels rise.”

Suburban schools will increasingly need to grapple with the needs of immigrant students, many of whom may not speak English when they arrive in school and who are more likely to live in low-income families than their white counterparts. It could be easier for suburban school districts, with their more manageable sizes, to adjust to newcomers. One might also hope that these demographic shifts suggest a move toward more desegregated school environments – a plus, since immigrant students have been shown to perform better in desegregated schools.

But the data suggest that living patterns are not necessarily getting more integrated, and many schools are already struggling with how best to serve these students. Their current problems provide a grim glimpse of the future.

It’s unclear if strategies currently being tried in urban school settings will work in suburban settings. (In many cases, it’s an open question as to whether they’re even working in urban settings.)

Do charter schools and school choice make sense in these smaller, less dense districts? Will the districts be able to afford interventions like preschool and alternative high schools when faced with decreasing tax bases? Will they want to do so in places where voters decide whether to vote the school budget up or down? Will it be harder to attract good teachers and school leaders and cull bad ones in the relative isolation of a suburb?

There are examples of suburban districts that have managed well; Montgomery County, outside Baltimore, is one of them. Discussions about what works best and what doesn’t work in struggling suburban schools are pretty rare, however. I suspect they’ll become more common in the very near future.

Is China’s top performance on international tests really so shocking?

Should we really be surprised that China’s students ranked first in the world this week on the international standardized test known as PISA? Probably not.

The test, administered every three years, is one of the main international assessments that give countries a sense of how their public school systems stack up against those in other countries.

It was the first time China participated in the test, and its students — all of them from Shanghai — not only came out ahead but trounced top performers like Finland and Singapore. On the math test, they scored 600, a whopping 38 points more than Singapore, which came in second. On science, they beat out Finland by more than 20 points for the top rank. On reading, they scored 556, 17 points ahead of South Korea, which finished second. The point differentials among other high performers were generally small.

Obama administration officials are stunned — Education Secretary Arne Duncan said the test results are a “wake-up call.” American education reformers are calling this another Sputnik.

There are caveats — Shanghai is, as the New York Times article points out, a “migration hub,” and the city may retain high-performing students who’d otherwise go home for high school. It is the country’s wealthiest city. But it is also seen as China’s flagship – the place that encapsulates China’s goals for itself and where it is testing ways to turn its national ambitions into reality.

China has been working toward this for a while. With an eye on transforming itself from a manufacturing economy that supplies the rest of the world’s consumers with goods into a middle-class consumer society that imports products from elsewhere, China has made unprecedented investments in education. (To become a consumer society, you need a middle class, and to create a middle class, you need good schools and high educational attainment, the logic goes.)

Besides improving its schools and increasing access and enrollment, China is trying to draw home the top students who in the past gravitated to U.S. universities. An article in this month’s issue of Foreign Policy notes that these changes came after China’s president called for major increases in high school and college enrollments in 1998.

This sounds familiar — President Barack Obama has repeatedly called for more investments in U.S. education and has set a much higher goal for the percentage of students graduating high school and enrolling in college, noting how far behind the U.S. has fallen in recent years and how badly this bodes for the country’s economic future. The PISA scores only underscore his message: American students scored about average for the 34 countries tested in reading and science, and below average in math. Shanghai students scored more than 100 points higher than American students in math.

Some education watchers are saying that these results could propel American leaders to get to work in earnest on reauthorizing the country’s main federal education law, the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (known as No Child Left Behind under President George W. Bush). But unlike Chinese leaders, Obama must contend with Congress in pushing forward his goals, and there is a huge divergence in thinking on what needs to be done to put the U.S. back in the running internationally.

A chance at higher education for illegal immigrants

With the news that Congressional Republicans have quietly collected signatures on a pledge to vote down practically any Democrat-backed legislation that comes their way, it seems certain that the DREAM Act is once again headed for failure when the Senate votes on it, likely sometime in the next few days.

The bill, which would give some illegal immigrant students the chance to earn permanent residency, has been introduced in every Congress this decade. Despite backing by many in the education world, it has yet to gather sufficient political support – particularly from conservatives.

Currently, because of a Supreme Court decision in 1982, illegal immigrants are granted a free education in American public schools. Although college is still a legal option for the tens of thousands of undocumented students who graduate high school each year, it’s next to impossible for many to afford college tuition. Ten states have passed laws since 2001 that would allow illegal immigrants to pay the cheaper in-state tuition at their universities, but these students are not eligible for federal financial aid, including Pell grants. And with the cost of college rising, post-secondary education has become even more out of reach for many undocumented students.

But as some programs begin to blur the lines between college and high school, some illegal immigrants might have a chance at obtaining at least some higher education. Dual credit programs – once thought of as a way for academically advanced students to get a jump-start on their college careers – are rapidly expanding as a means for disadvantaged students to get exposure to college.

Programs like early or middle colleges give students the opportunity to earn college credit while still in high school. And at least one program – the Early College High School – provides a framework where students can potentially earn their associate’s degree along with their high school diploma.

Still, most illegal students attend traditional high schools where they don’t have the chance to earn college credit. And even those who manage to pull in the 60 credits required for an associate’s degree while in high school will still have illegal status as they try to find a job.

But with legislation like the DREAM Act continuously stalled in D.C., taking advantage of one of these expanding programs might be some students’ best chance at furthering their education for a while.

Progress on the dropout crisis?

The Johns Hopkins researchers who in 2002 counted 2,000 “dropout factories” in the U.S. — high schools that graduate fewer than 60 percent of their students within four years — are reporting that there’s been significant progress in reducing the number of those schools.

“The number of dropout factories fell by 13 percent – from 2,007 in 2002 to 1,746 in 2008,” says the report, released jointly with America’s Promise Alliance and Civic Enterprises. Also from 2002 to 2008, the overall high school graduation rate in the U.S. increased three percentage-points, to 75 percent.

New York and Tennessee increased their graduation rates the fastest — by 10 and 15 percentage-points, respectively. So what did they do right?

In New York City, one approach has been to close schools with low graduation rates. Besides causing an outcry among parents and teachers, this approach hasn’t always yielded all positive benefits, as we’ve written about previously. (For an in-depth look at the arduous process of closing a school, I recommend the GothamSchools series that has followed the effort to shut down Columbus High School in the Bronx along with two others.)

The Johns Hopkins researchers report that New York state has only 16 fewer dropout factories than it did in 2002 (the city alone is closing or in the process of closing 35 high schools), while about 61,000 fewer students are enrolled in dropout factories. Those numbers would suggest that something else was going on besides just closing schools.

The report cites various strategies, including early-warning systems that pinpoint students at risk of dropping out before they actually do so. Such systems also encourage districts to start monitoring at-risk students in middle school. In New York City’s case, one factor that seems to have been especially effective was creating alternate pathways for at-risk students so they could catch up on missed credits or return to school after dropping out.

In Tennessee, students who drop out of high school before age 18 don’t get to keep their driver’s license. The report also cites the state’s embrace of value-added assessment, its targeted support for struggling schools and its strong leadership.

This is not to say, however, that New York and Tennessee should sit back and be satisfied. Going from a 60 percent graduation rate to a 75 percent graduation rate is a different project than raising the rate from 75 percent to 90 percent — which is the target for the year 2020 set out in the report. The going is just about to get tough.

Experience necessary?

The outcry over Mayor Bloomberg’s proposed appointment of Cathleen Black to head the New York City public schools may have taken his administration by surprise, but perhaps it should have been expected. The controversy over Black is not just about her, or New York City. The choice of Black highlights an issue that is at the heart of some of the most furious debates in education these days:

Have educators had their chance to fix things but left the public schools so broken that they need an infusion of new perspectives and ideas from outsiders?

Or are the reformers from business and law backgrounds (like Black, Joel Klein and the hedge funders who support charter schools) a group of neophytes whose lack of experience in education is potentially damaging to the children they’re trying to help?

This fight has been simmering, and often boiling over, for the past decade as reformers in the mold of Klein and Michelle Rhee (who was criticized for a slim teaching resume when she took over the D.C. public schools) have expanded their role in education. And it goes much deeper than who should run school bureaucracies.

This question underlies the battle over teacher pay: Should teachers be paid for their years of experience, or should the seniority system be scrapped and teachers paid based on their performance?

And how we should recruit teachers in the first place: Should we rely mainly on the traditional routes to a teaching job through education schools? Or draw more heavily from nontraditional routes, including recruiting high-achieving students straight from college, in the case of Teach for America, and successful professionals, in the case of programs like the Teaching Fellows? What about principals?

Black is an extreme example. She has never taught, and she attended private schools and sent her children to them, too. Thus the particularly angry showdown in this case. But it’s certainly not a new fight.

In Republican-controlled House, will many federal education programs be cut?

U.S. Rep. John Kline (R-MN), fresh from re-election to a fifth term and about to be part of the new Republican majority in the House, said this morning that there are 60 federal education programs that could be cut or combined.

In an interview on Minnesota Public Radio (MPR) with Cathy Wurzer, Kline didn’t list the unnecessary programs — there wasn’t time — but said Democratic leaders agree with him that many could be scaled back. And he said the No Child Left Behind law needs major work.

Kline’s views on education are significant — he’s expected to chair the House Education and Labor Committee in the new Congress.

Unlike some other Republicans, he doesn’t agree that the Education Department has to go, but said:

“It’s worth looking at the department to see what it’s doing and understand what the role is and should be. In my judgment, it is clearly less than it has grown to be.”

MPR’s Elizabeth Dunbar summarizes the nine-minute interview here.

A version of this post, by Joe Kimball of MinnPost, was published on MinnPost.com on November 18, 2010.

Competition and public schools: A look at Florida

Will injecting competition into the educational system save America’s schools? The idea — that if public schools are forced to compete for students (and therefore for funding), they’ll find ways to improve themselves — has been around for decades. Without the pressure of competition, proponents of school-choice argue, schools stagnate.

This thinking has led to voucher programs, in which parents receive taxpayer money to send their children to private schools, as well as the expansion of charter schools, which are independently operated public schools that are free of many of the constraints facing other public schools.

But does competition really work? A new study says yes. Published in Education Next, the study looks at the Florida tax-credit scholarship program, which gives tax credits to corporations for donations to scholarship-funding organizations. Similar programs helped pay for 104,000 students nationally to attend private schools in 2008-2009 (compared to just 60,000 students who used vouchers to attend private schools), according to the study. Last year, 29,000 students in Florida took advantage of the tax-credit scholarship program.

The authors find that students at public schools facing a greater threat of losing them to private schools improved their test scores more than their peers at other schools, and that “this improvement occurs before any students have actually used a scholarship to switch schools. In other words, it occurs from the threat of competition alone.”

The reported gains were small but statistically significant. For example, “for every 1.1 miles closer to the nearest private school, public school math and reading performance increases by 1.5 percent of a standard deviation in the first year following the announcement of the scholarship program.” Other factors that appear to have positively influenced scores are the number and types of private schools nearby.

This study adds to a growing body of research that looks at competition and its effect on traditional public schools. Research on whether charters can help raise achievement at all schools has come back mixed. And some charter-supporters I’ve talked to recently (as well as their opponents) have conceded that the idea of improving failing districts through competition — which sounded good in theory — hasn’t happened in reality.

Even with mixed results, though, school choice doesn’t seem to be losing any momentum. Having a definitive answer to the question of whether competition improves all schools appears not to be a prerequisite for the expansion of voucher programs and charters.