California ballot initiative seeks to expand access to online education

By Joanna Lin, California Watch

For public school students in California, where you live usually determines where you can learn. To David Haglund, that’s not right.

This month, Haglund, principal of the Riverside Virtual School, an online independent study program run by the Riverside Unified School District, introduced a statewide ballot initiative [PDF] that would give students unrestricted access to publicly funded courses – wherever they are.

The California Student Bill of Rights Initiative is “designed to eliminate control by ZIP code,” Haglund said.

Under the proposal, schools, districts and county education offices would be required to make available to all students the courses needed for admission to the state’s universities. Those courses, known as A-G requirements at the University of California and California State University, could be offered at a student’s school or district of residence or any other publicly funded school, and they could be classroom-based, online or a blended model of the two.

Nearly 27 percent of California public high schools in 2007-08 offered too few A-G courses for all students to take them, according to an analysis [PDF] by UCLA’s Institute for Democracy, Education and Access.

“We in our public school system in California say, ‘If you don’t live within so many square miles of a building, you can’t play,’ and that’s not fair,” Haglund said. “And it’s particularly unfair when the infrastructure and technology exists to resolve those issues.”

Skeptics of the initiative say that while the proposal attempts to address real problems in education access and equity, it’s not the right mechanism to do so. If passed, the initiative could send more public money to private companies, they say.

The initiative calls on the state to modify its school financing system so that average daily attendance is apportioned to the courses students complete, allowing multiple institutions to split funding for the same student. Currently, online education in California operates as independent study programs, or charter or private schools – models that initiative supporters say limit access to virtual learning.

“The idea is if the funding is attached to courses, the schools might be more willing to investigate how to make those courses available,” Haglund said.

John Rogers, director of UCLA IDEA, sees a different outcome: “Splitting up a student’s ADA (average daily attendance) potentially can weaken the home institutions,” he said. “When there are efforts to supplant aspects of the existing public education system with a cheaper online alternative, you’re going to diminish the overall quality of public education, and you’re going to exacerbate, not remedy, inequalities.”

The initiative “could wreak havoc on the delivery of public education in the state,” said John Affeldt, managing attorney for Public Advocates, which is representing organizations and families challenging the constitutionality of California’s school funding system.

“It seems at first blush to be more about an online provider’s bill of rights to get public money to provide online courses than an initiative to make sure we have equitable access to education for all kids,” he said.

Haglund said, “The initiative is not designed to destroy public education.”

“California as a state has pushed educational innovation into the private and charter school space. If that’s where we want to go, then keep it up,” he said. “But if we want our kids in public schools to have access to the same type of high-quality education they can have elsewhere, we need to switch it up.”

‘The Old West’

Haglund’s proposal comes at a time when more students are going to school by logging on to their computers. At least 15,000 students in California are enrolled in full-time online charter schools, and more than 3,600 were enrolled at Riverside Virtual School, the largest district-run program in the state in 2009-10, according to a review by the Evergreen Education Group.

But unlike many states that have embraced – or at least accepted – online education, California has stayed on the sidelines.

“There is no statewide provision for online learning in California. It’s all facilitated through individual districts who make up their own thing as they go along; consequently, it’s like the Old West,” Haglund said. “You’ve got everybody and their grandmother out there doing something, but nobody knows what that something is.”

Lawmakers – including state Superintendent of Public Instruction Tom Torlakson when he was a state assemblyman – have tried repeatedly to expand access to online education through changes to ADA guidelines.

Torlakson is currently assembling an advisory board to rethink technology in the classroom and is looking to raise $250,000 to fund its work. His long-term goal is to provide every student with a digital learning device, said Jason Spencer, a legislative representative for the superintendent. Although funding online education is a piece of the puzzle, it’s an issue for the Legislature to decide, he said.

Haglund and his colleagues at Education Forward, a nonprofit formed to sponsor the initiative, said they are tired of waiting.

“Is it possible for the Legislature in Sacramento to deal with this much more quickly and efficiently than this process? Yeah, absolutely,” said Rick Miller, superintendent of Riverside Unified and a director at Education Forward. “But they haven’t done it. It doesn’t mean they can’t and they won’t – they just haven’t. How long should we wait?”

Miller and Haglund said they are sponsoring the initiative as individuals, not on behalf of their district. But their experience in Riverside has helped them craft some guidelines for online education.

Under the initiative, only online courses approved by UC and schools accredited by the Western Association of Schools and Colleges would be eligible for public funds. Student participation in virtual learning would be voluntary.

After it’s cleared by the state for circulation – a target date is set for next month – the initiative will need 504,760 signatures to qualify for the November 2012 ballot. More than likely, it won’t be the only online education proposal Californians see next year.

Language in the initiative could end up in legislation next year, said Jeff Frost, a lobbyist for several education organizations and school districts, including Riverside Unified. Along with other school district lobbyists, Frost has developed seven principles for online learning that he hopes will lay a foundation for state policy.

“The Department of Education, Department of Finance and key legislative staffers are skeptical that if the kid’s not in a room with a teacher, they’re not sure what level of learning is actually going on,” Frost said. “We’re working on language … to reach some kind of harmony in the issue.”

That language, Frost said, will support the notion that ADA can be calculated based on student work.

“Whether they’re in the virtual school’s learning center or whether they’re at home with their mom looking over their shoulder or whether they’re in the public library – if they’re there working, that’s the same as a kid who showed up in school,” Frost said.

Assemblyman Bob Blumenfield, D-Van Nuys, said technology provides tools to verify that students are learning outside the classroom.

“In the traditional classroom, you can’t verify if that student is looking out the window and daydreaming about something else, whereas an online class, you can. You can make sure that person’s butt is in the seat when they say it’s supposed to be. … The technology is out there and improving every day as we speak.”

Blumenfield wrote bills this year and last to expand online education. Those efforts will be reincarnated in January as a state Senate bill, he said. Like previous legislation, it will call for proctored, in-person exams.

As for how online education should be funded, Blumenfield said he’s “somewhat agnostic.”

“My goal is I want to get it done,” he said.

This piece originally appeared in California Watch, the state’s largest investigative reporting team and a project of the independent, nonprofit Center for Investigative Reporting. Contact the reporter at jlin@cironline.org.

Charter-school enrollment: Two million students and counting

The charter-school movement reached a milestone this week: Charter schools, which are publicly funded but typically privately managed, now educate more than two million students, up from around 1.8 million last year. Despite the heated debate over charter schools, the number is still relatively small considering the size of the K-12 student population in U.S. schools: 55.4 million, according to the federal government’s most recent “Digest of Education Statistics.”

The announcement, made by the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools (NAPCS), comes as some states are lifting caps on the number of charter schools, and as major charter-management organizations (CMOs) like KIPP and Rocketship Education are receiving federal dollars to expand their programs.

“To some extent, there’s a muscling aside of the small mom-and-pop-type charters by the more networked charter-management-organization-run charters that depend on a larger scale,” said Jeffrey Henig, a professor at Teachers College, Columbia University, who has studied charters. “A lot of them started early on at lower grade levels with adding a grade a year, so this is a building-out that’s been reasonable to anticipate.”

Related Stories

New Jersey greatly slows charter school growth

Shortage of qualified leaders imperils charter movement

More than 500 charters opened for the first time in the 2011-12 school year, the greatest growth since the charter movement began in Minnesota in 1992. According to NAPCS, more than 200,000 students are attending a brand-new charter school this fall, and 400,000 more are on waiting lists. Nearly half of the country’s 5,600 charter schools are concentrated in just five states: Arizona, California (where 20 percent of them are located), Florida, Ohio and Texas.

While a record number of charter schools have opened this year, 150 were shuttered for either low enrollment, financial troubles or weak academic performance, according to NAPCS. Charter critics often point to data showing that only 17 percent of charters outperform nearby traditional public schools, but proponents say closures are evidence that charter-school laws are working.

Henig explains that while he thinks charters will continue to see their enrollments grow, “two million is still a drop in the bucket for the overall public-school population.” He says that successful CMOs are sometimes pressured by the U.S. Department of Education and philanthropic foundations into expanding more quickly than they’d like.

“It’s pretty clear charters are a reform that’s here to stay,” says Henig. “And all of that despite the fact that the evidence of their greater effectiveness is limited.”

Should schools alone be held accountable for student achievement?

What if schools didn’t have to work alone to improve student achievement? That was the question we asked in a recent article about the miserable state of public education in Camden, N.J., one of the poorest cities in the country. Now, a study out today by Education Sector, a Washington, D.C.-based education policy think tank, delves further into the question of whether public schools should share responsibility for improving the academic outcomes of impoverished children.

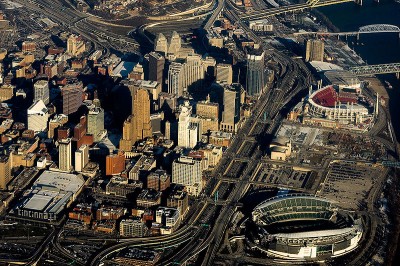

In Cincinnati, schools and other agencies are sharing responsibility for student results (Photo courtesy of Kevin Hartnell under a Creative Commons License)

The argument is that non-school agencies—after-school organizations, public housing departments, local colleges and universities—should also be held accountable for student success. The report’s authors—Kelly Bathgate, Richard Lee Colvin and Elena Silva—note that this is far from a simple idea to execute, however: “Some critics fear that broadening accountability for academic results beyond the schools will weaken promising school reforms. And they are right that if everyone is accountable for results, then, in fact, no one is.”

In Cincinnati, the focus of the report, a coalition of agencies tried to avoid this problem by making a list of goals for each organization involved that fit with its specific mission. In the case of a mentoring organization, the report says, goals might have included “improving the mentees’ attendance, reducing the number of times they get in trouble, and following them to track whether they are graduating from high school and enrolling in college.”

But the experiment’s outcomes so far are mixed.

“Over the past four years, the communities showed progress on 40 community indicators. More students are demonstrating proficiency in math and reading and enrolling in college. One particularly bright spot is that the percentage of children who come to kindergarten ready to learn has risen substantially,” the report’s authors write.

“But,” they go on to say, “there is a long way to go. The percentage of students graduating from Cincinnati Public Schools who enroll in college within two years of high school graduation was 65 percent in 2009, an increase since 2005, but a 4 percentage point drop from the previous year.”

The project in Cincinnati may have implications for the future of the Obama administration’s Promise Neighborhoods initiative, which was meant to replicate the Harlem Children Zone’s model around the country. For more details about the Cincinnati project and its results thus far, see the full Education Sector report, “Striving for Student Success: A Model of Shared Accountability.”

Kindergartners at the keyboard [podcast]

In October, Hechinger Report writer Jill Barshay reported on computer instruction in kindergarten classrooms in a story that ran in Education Week and newspapers across the country. Last week she was a guest on American RadioWorks, where she spoke with executive editor and host Stephen Smith about the story.

The new G.I. Bill: Big money, big challenges [podcast]

Roger Parker, Jr. (US Army-Ret) helps his grandson Tyrell Parker, 9, whom Parker is raising, work on his homework at their apartment on September 12, 2011 in Pasadena, Md. (Photo by Ricky Carioti/The Washington Post)

In September, Hechinger Report writer Jon Marcus reported for The Washington Post that universities were heavily recruiting veterans to get a piece of the $11 billion made available through the new post-9/11 G.I. Bill, but providing little of the additional support that many veterans say they need. Marcus was a guest on the public-radio program Here & Now, where he talked more about the story.

How a “tech break” can help students refocus

Psychologist Larry Rosen laments the fact that technology is driving us all to distraction. This past weekend, he spoke at a Hechinger Institute seminar for education reporters, which focused on how digital media are transforming teaching and learning in U.S. schools. The seminar, held in Chicago, was made possible by support from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation.

In a forthcoming book, iDisorder, Rosen argues that all our tech gadgets and applications are turning us into basket-cases suffering from versions of obsessive-compulsive disorder and attention-deficit syndrome.

“Kids are thinking all the time, ‘Oh my god, who texted me? What’s on Facebook?’” says Rosen, a professor at California State University-Dominguez Hills. He says the average computer programmer or medical student can only stay focused on a task in front of him- or herself for three minutes.

Rosen has suggestions for fighting back, and some of them are counterintuitive. Instead of resisting the urge to text, check Facebook or watch a YouTube video, Rosen says just do it. That’s right: Cure the tech disorder with a dose of more technology!

Related Stories

Q&A with Lisa Gillis: Rethinking how we educate ‘digital natives’

Q&A with former Gov. Bob Wise: What will a ‘digital’ school look like in 5 years?

Rosen calls it a tech break. But rather than taking a break from technology, you give yourself permission to embrace technology for a particular amount of time, be it one minute or 15. “It works amazingly,” he says.

Here’s why: If your brain keeps thinking about a text message you need to return, it’s better to send that text to get the nagging impulse out of your head. Once you stop thinking about sending that text, then you’ve literally freed up space in your brain to focus on more important things, like solving the global energy crisis or creating world peace. Or, just getting that research paper done.

The trick is to be disciplined and only take tech breaks at predefined intervals. One example would be to work hard for 10 minutes, and then allow yourself one minute to check email. For a child doing homework, Rosen suggests rewarding the child with 15 minutes of tech time for each half-hour of focused study. Rosen advises giving the child an option of spending the 15 minutes immediately or accumulating it for later use. After all, you need more than 15 minutes to get into a good video game.

Rosen’s theory has interesting implications for schools. Would kids be more focused and productive if teachers told students to take their cell phones out of their lockers and check their texts in the middle of every class?

Fortunately, there are other effective ways to reset the brain. Rosen lists a bunch: listening to beautiful music, looking at art and practicing yoga. Or going outside for a hike.

Students as software testers

How do advocates of digital learning know that students learn better via computers than more traditional methods? Katie Salen is tired of hearing people say, ‘Prove to us that technology works before we buy it.’ She says waiting for irrefutable proof is the wrong approach.

Salen—a professor in DePaul University’s School of Computing and Digital Media—developed an educational model that uses video games in the classroom. It’s used by Quest to Learn, a two-year-old public school in New York City, and ChicagoQuest, a charter school that opened this fall in the Windy City. Salen is a co-founder of Quest to Learn.

She’s also a game designer.

Salen says game designers don’t aim to make perfect, proven products before they put them out on the market. That, she says, is how textbook publishers work.

Instead, she says, video-game companies develop products with users. They might issue an early version with kinks or bad ideas. And then it’s a dynamic process where user feedback helps the designer improve a game. There’s constant fixing. The video game is ever evolving.

She’d like to see schools experiment with education software in the same way, rather than waiting for definitive proof that certain products work. The more students play with educational games, the more game designers can make them effective.

Related Stories

How a “tech break” can help students refocus

Q&A with Lisa Gillis: Rethinking how we educate ‘digital natives’

Q&A with former Gov. Bob Wise: What will a ‘digital’ school look like in 5 years?

In the meantime, the evidence is mostly anecdotal, from the “everyday transformations” that Salen sees happening in classrooms to student victories over competitors from other schools—such as the video-game-trained students from Quest to Learn who recently won a math competition.

With concentrated poverty on the rise, should ed reformers be worried?

The number of people living in concentrated poverty rose substantially over the past decade, according to a Brookings Institution report published on Nov. 3rd: “After declining in the 1990s, the population in extreme-poverty neighborhoods—where at least 40 percent of individuals live below the poverty line—rose by one-third from 2000 to 2005–09.”

Education reformers who ascribe to the No Excuses movement have argued that poverty shouldn’t be used an excuse for writing kids off, and the recent release of scores on the National Assessment of Educational Progress show that the gap between poor students and their more affluent peers didn’t grow during the recession.

Still, research has found that concentrated poverty is associated with lower academic outcomes, and that more poverty makes the job of educating children more difficult. Kids living in poverty often have to deal with other problems—homelessness, domestic violence, health issues—that make it hard for them to concentrate on their schoolwork, and their parents are less likely to be well-educated than other parents. But there’s also an added negative effect of concentrated poverty, above and beyond the effect of poverty at the individual level. In short, concentrated poverty can make bad situations exponentially worse. Among other things, it’s much harder to attract and keep quality teachers in poor neighborhoods.

Concentrated poverty is not rising everywhere, however. In New York City, Washington, D.C., Baltimore, New Orleans, and Los Angeles, the number of people in high-poverty neighborhoods declined over the past decade, according to the report. Around New York City, the number dropped by more than 200,000, to reach about 800,000 living in low-income tracts in the metropolitan area.

In other education reform hotspots, however—including Denver, Houston and Memphis—it’s on the rise.

Check out the cool map on the Brookings website to see if the city where you live saw concentrated poverty rise or fall in the past decade.

NAEP scores rise, but income gap sees little change

Fourth- and eighth-graders’ scores showed modest improvement and racial achievement gaps narrowed on the 2011 National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), commonly known as the “Nation’s Report Card,” which was released Tuesday. The gap between disadvantaged students and their more affluent peers remained largely unchanged, however, and widened in fourth-grade reading.

Compared to 2009, this year’s NAEP scores rose by one point in fourth- and eighth-grade math and eighth-grade reading, but stayed flat in fourth-grade reading. Since 1992, the year NAEP began, math scores have risen substantially, but reading scores have seen only minimal gains.

The black-white score gap closed by one point in both fourth- and eighth-grade math, and the Hispanic-white gap narrowed by one point in fourth-grade math and four points in eighth-grade math. In fourth-grade reading, however, the black-white gap widened.

Perhaps most interesting, there were gains in both reading and math across all income levels, even as the number of people living at or below the poverty line has grown and income gaps widened.

This year’s math results are the highest ever in both fourth and eighth grade. There were also gains in reading, especially among students who receive free- or reduced-price lunch, the indicator used by NAEP to identify poverty status.

Overall, both students living in poverty and more affluent students saw score increases in fourth-grade reading, but six states — Oregon, Washington, West Virginia, Vermont, New Hampshire, Maine — and the District of Columbia saw the income gap widen.

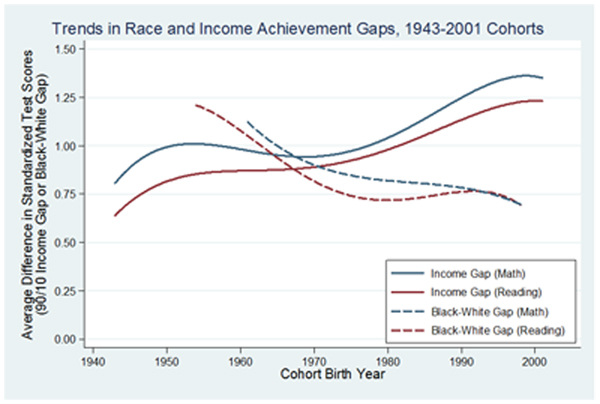

Race and Income Achievement Gap Trends (Courtesy of Sean Reardon; based on analysis reported in "Whither opportunity? Rising Inequality, Schools, and Children's Life Chances")

Sean Reardon, a professor and researcher at the Stanford University School of Education who studies the income achievement gap, says that the widening of the gap in these states could be due to a number of factors, including increased segregation, differences in teacher quality at poor and affluent schools, and varying No Child Left Behind requirements by state. He is currently conducting research to examine how state policy and demographic shifts may influence the income gap.

Reardon also said NAEP’s data on poverty may not be completely reliable because it is self-reported by students and leaves out many other factors.

“It won’t be a complete story,” Reardon said. “Because NAEP doesn’t do a good job of providing detail on income.”

While modest gains were seen in many areas, this year’s results pale in comparison to the gains made in the 1990s, a cause for worry according to U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan.

“The modest increases in NAEP scores are reason for concern as much as optimism,” Duncan said in a statement. “It’s clear that achievement is not accelerating fast enough for our nation’s children to compete in the knowledge economy of the 21st Century.”

Calculating how much college actually costs

Days after the College Board announced that tuition at America’s public universities increased 8.3 percent this year, higher-education institutions quietly met a weekend deadline for reporting what students actually pay, after grants and other financial aid are taken into account.

The “net price” accounts for tuition minus scholarships, grants, and income from on-campus jobs, on average, for a full-time first-year undergraduate. It’s typically much lower than the so-called “sticker price.” But universities have been reluctant to disclose net prices, fearing that students and their parents would demand deeper discounts—and that many would resent learning that they pay more than some of their classmates.

“There’s some concern … that they will anticipate that that’s exactly what their financial aid will look like,” said Jane Brown, vice president of enrollment at Northeastern University in Boston.

The so-called “net price calculator” was required by the Higher Education Opportunity Act of 2008, but many universities waited until the October 29th deadline to post the data. A spot check showed that some still had not provided the information at all.

The College Board estimates that fewer than 12 percent of students at private colleges and universities—and about half of those at public universities—pay the full advertised price.

Advocates for providing net price data say that doing so is the only way students can know the real cost of college—including those who may be discouraged by the list price.

“It’s an incremental step,” said Jamie Merisotis, president of Lumina Foundation for Education, which advocates for higher enrollment and graduation rates and which is among the funders of The Hechinger Report.

“These efforts at transparency are very useful. We’re going to have to do more to better inform current and prospective students,” Merisotis said.