Teachers want the role of unions to change, survey says

Critics have portrayed teachers unions as impediments to reform efforts around the country because they have fought against changes such as pay-for-performance and the abolition of tenure. But stories of unions working with school district officials to craft new teacher quality initiatives are slowly becoming more common. And, according to a new study that surveyed more than 1,000 teachers, that’s exactly what a growing number of teachers think unions should be doing.

“Trending Toward Reform: Teachers Speak on Unions and the Future of the Profession,” released Tuesday by Education Sector, a nonprofit education think tank located in Washington, D.C., reveals that teachers are more likely to think unions should help with and even lead reform efforts than they were five years ago.

In 2007, 32 percent of teachers said that unions should focus more on improving teacher quality. In 2011, that number was 43 percent. Just 14 percent of teachers thought that union involvement would be an obstacle in reform efforts while 62 percent said unions could be “helpful partners in improving schools.”

Yet, when it came down to the specifics of how the teaching profession should be improved, teachers didn’t necessarily agree with many of the in-vogue education trends, such as merit pay, overhauling teacher evaluations to include student test scores and eliminating tenure.

For instance, only a third of teachers are in favor of rewarding those whose students get high test scores. Forty-six percent liked the idea of giving more money to teachers whose students make more academic progress than other similar students, which is similar to how many merit pay programs across the country are structured.

Far more teachers were in favor of raising the salaries of teachers who work in low-performing schools (83 percent) or who teach in hard-to-fill subject areas like math or science (58 percent). In other words, teachers are likely to support differentiated pay, but in the areas where they have the most control, said Sarah Rosenberg, a co-author of the study.

Few teachers are happy with the idea of eliminating tenure altogether, which traditionally is earned after a certain number of years in the profession and provides a degree of job protection. Critics argue tenure policies make it nearly impossible to fire poor teachers. While teachers agree that tenure shouldn’t protect bad teachers, only a third would be willing to trade it for a $5,000 bonus, according to the survey.

Still, a growing number of teachers believe that unions should play a role in making it easier to fire ineffective teachers. “Teachers pay the greatest price for incompetent teachers,” one teacher wrote in response to the survey. “Year after year, [other teachers] pick up the slack.”

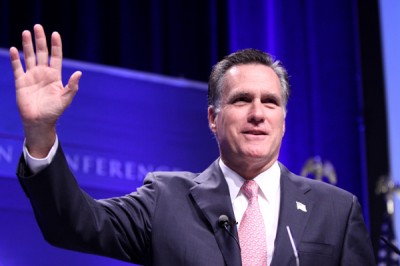

Ed in the Election: Romney advisor talks unions

Presumed Republican presidential nominee Mitt Romney’s top education adviser, Rod Paige, gave an interview to The Root this week. A former Secretary of Education under George W. Bush, Paige talked about the role of the federal government in education, school choice and teachers unions, but made it clear that he was not speaking for the campaign.

“I think that the teacher unions represent one of the most damaging burdens on reform initiatives to improve schools,” Paige told The Root. “There’s an important role for teachers unions, but they have grown to a point where they are too powerful. And that is a detriment to school reform. School reform is not going to happen, because they are not going to support anything that significantly changes the status quo. They are only going to support the marginal issues.”

In a week full of Supreme Court decisions, education was once again largely overlooked on the campaign trail. But that doesn’t mean schools won’t be affected by news from Washington, D.C. The Supreme Court’s ruling to uphold the Affordable Care Act, President Barack Obama’s signature legislation mandating all citizens get healthcare coverage or pay a fine, could be connected to educational outcomes, suggests an Education Week blog post that cites several studies.

Romney has vowed to repeal the healthcare law should he be elected.

Also this week, Congress reached an agreement to prevent the doubling of interest rates on student loans, from 3.4 to 6.8 percent. Both Romney and Obama have been vocal about the need to freeze those interest rates. The compromise is included in a transportation bill expected to pass both houses easily.

While interest rates would stay the same, limitations would be placed on how long students are eligible for subsidized loans—up to six years in a four-year degree program, or three years in a two-year program. Right now, eligibility is not based on how many years a student has been enrolled in a program.

Universities scolded for raising tuition, chasing ratings

WASHINGTON, D.C.—Public universities observing the 150th anniversary of the federal law that led to their creation found their celebration tempered Tuesday, June 26th, by stern calls to restore their original purpose of making higher education available to everyone.

Billionaire philanthropist Bill Gates told university presidents and others gathered in Washington that their pursuit of higher rankings had led them to become too selective in admissions and to lavish financial aid on students who don’t need it. (Disclosure: The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation is among the funders of The Hechinger Report.) U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan challenged university leaders to make more information available to students about the real costs of college, and the likelihood of actually graduating.

“As public institutions, your prestige comes from a commitment to equity, opportunity and excellence,” Gates said at the commemoration of the 150th anniversary of the Morrill Act, which paved the way for more than 70 public and a few quasi-public and private universities. “It is not a point of high status to keep students out.”

Signed by President Abraham Lincoln on July 2, 1862, the Morrill Act—named for the Vermont congressman who introduced it—set aside federal land to be used or sold to establish public universities that would come to include Auburn, Cornell, MIT, Purdue, Rutgers, Virginia Tech, the University of California system, and the universities of Arizona, Florida, Georgia, Maryland, Minnesota, Nebraska and Wisconsin, plus Colorado, Iowa, Michigan, Ohio and Pennsylvania state universities.

Lincoln signed the measure into law as the Civil War was under way, said Duncan, because he understood the nation was fighting for equality “not just in law, but in life.” And Gates said increasing college costs have put the nation on “a path that may lead us away from the historical commitment to equity and opportunity.”

Yet universities are dangling financial aid in front of high-achieving students to improve their standing in U.S. News & World Report and other college rankings, Gates said, while students who need it can’t get it.

“Money is being spent on students who may actually need the least help,” Gates said.

Meanwhile, Duncan said in separate remarks, “out-of-control tuition costs” continue to rise.

“We’re cutting off our nose to spite our face and doing our young people a great disservice,” he said. “At a time when college has never been more important, it also unfortunately has never been more expensive.”

He challenged the university officials, including many presidents, to make themselves more accountable by joining a small handful of schools that have agreed to publicize the true cost of college, how much of available financial aid consists of loans rather than grants, the estimated monthly repayment amounts on those loans, and how many students ultimately graduate.

Ed in the Election: Agreement on vouchers and stalemate over student loans

College Board, the group best known for administering the SAT, this week launched “Don’t Forget Ed,” an effort to make presidential candidates pay more attention to education, by setting up 857 empty school desks on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. The desks represent the number of students who drop out of high school each hour of each school day, according to a 2007 Education Week statistic. (Although, as the Associated Press reports, that figure may be off.)

College Board, the group best known for administering the SAT, this week launched “Don’t Forget Ed,” an effort to make presidential candidates pay more attention to education, by setting up 857 empty school desks on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. The desks represent the number of students who drop out of high school each hour of each school day, according to a 2007 Education Week statistic. (Although, as the Associated Press reports, that figure may be off.)

The organization also gathered signatures in an online petition directed at the presidential candidates. The petition reads, “If you want my support, I need to hear more from you about how you plan to fix the problems with education. And not just the same old platitudes. I want to know that you have real, tangible solutions, and that once in office, you’re ready to take serious action. I’ll be watching your acceptance speech at your party’s convention.” Over 22,000 people have signed so far.

It was still a quiet week for education on the campaign trail, though, with most of the action happening at Capitol Hill. President Obama and his administration struck a deal with Congress to keep a Washington, D.C., school voucher program alive. The presumed Republican nominee Mitt Romney and other Republicans have criticized Obama for trying to cut funding for the Opportunity Scholarship Program, which allows low-income students in the District to apply for scholarships to be used at private schools.

The deal, worked out with House Speaker John Boehner (R-OH), requires an increase in “the current enrollment of about 1,615 to approximately 1,700 students for the coming year to allow for a statistically valid evaluation of the program,” according to a written statement by Education Secretary Arne Duncan on Monday. He clarified the next day that this did not mean the Obama administration had changed its position on vouchers, which it opposes.

Obama has also been battling Congress on student loans this week. If an agreement is not made by July 1, the student loan interest rate will double from 3.4 percent to 6.8 percent. Obama and Republican leaders both say they would like to freeze the interest rate, but have not agreed on how to pay for it. Romney has also said he supports freezing it at 3.4 percent.

“We’re 10 days away from nearly 7.5 million students seeing their loan rates double because Congress hasn’t acted,” Obama said in remarks to a group of students at the White House. “This should be a no-brainer. It should not be difficult. It should have gotten done weeks ago.”

Republicans have said that they are willing to find a solution, but say the administration is being uncooperative. As the Washington Post reports: “In Capitol Hill, GOP leaders complain that Obama’s public remarks are at odds with his administration’s refusal to engage in serious negotiations on how to pay for $6 billion in subsidies for the federal Stafford loans. Republicans say that they are ready to make a deal and have offered proposals to Democrats but that the White House has blown them off in favor of Obama’s making public speeches.”

Reforming the way we write about reform, education and more

Several years ago, an older and wiser colleague of mine at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel gently chided me for using the phrase “inner-city” in my newspaper articles on Milwaukee’s schools. My co-worker, Jamaal Abdul-Alim, pointed out that most of the neighborhoods and sections of Milwaukee to which I ascribed that label were not part of the city’s core. If I meant low-income, predominantly black, high in crime, or some combination of all three, I should say so more plainly, he advised.

The exchange prompted me to think more explicitly about language as I wrote about education in the decade that followed. Some days, the pressure of deadlines made me negligent; and at least a few times I let simplistic, misleading, or jargon-laden language slip into my writing out of sheer laziness. But overall I believe Jamaal’s comment helped make me a more deliberate and considerate writer.

I was reminded of the importance of language during a recent virtual discussion among reporters about the overuse, and misuse, of the term “reform” in education writing. Several journalists pointed out that labeling a change in policy or approach a “reform” (or an advocate of such change a “reformer”) carries a positive connotation since the word means improvement. They expressed concern that journalists who use the term implicitly express support for a controversial education agenda—including charter schools and linking teacher pay to student test scores.

Journalists should certainly strive to ensure they don’t unthinkingly support a given political agenda through the appropriation of its rhetoric. But as the political debate surrounding public education grows more heated, I worry that we all—journalists, educators and policymakers included—are missing the point when it comes to our words. The main reason we should be more scrupulous in using terms like “reform,” “inner-city,” “value-added,” “at risk,” “learning deficit” or “overage” is not to avoid appearing complicit with a given agenda. We should eschew such terms because they undermine and devalue the primary mission of public education and the journalism that documents it: communicating with children and parents.

No thoughtful person would tell a mother: Your at-risk, overage child’s failing school will be reformed, and value-added testing introduced, because of the students’ many deficits. Yet the sum of our worst, laziest rhetoric can have that same effect. At best, such misguided language confuses families, leaving them disengaged. At worst, it offends and alienates families, leaving them enraged. Almost always, it erodes trust with public education’s core constituency.

Just weeks before I had the conversation about the term “inner-city,” I wrote about a national effort to overhaul high schools by making them smaller. I decided to follow over the course of a year a struggling Milwaukee high school called North Division, the first in that city to be broken into smaller schools. In the first installment of the series, I wrote that students and teachers at North Division were “guinea pigs” in a nationwide push for smaller high schools. I thought nothing about the term until I learned, weeks later, that I had deeply offended many people in the North Division community by likening them to animals.

I had used “guinea pigs” as a figure of speech countless times. But through conversations with students and staff at North Division, I realized they viewed the term very differently: What I thought of as a flip cliché was to them yet another denigration of a school and community that had, for generations, been unfairly and sweepingly labeled as “violent,” “failing,” “notorious,” “out of control” and “dangerous.” What’s more, it conjured up a painful, not-too-distant history in which poor, black people were literally used as human subjects in unethical science experiments. I could rationalize forever about what I had meant—and not meant—by the words. But in the end, all that mattered was how they had been received.

Ed in the Election: Obama’s pseudo Dream Act and Romney’s voucher proposal

Each week leading up to the 2012 Election, HechingerEd will feature a post rounding up the latest on what the candidates are saying and doing about education – and what others think of their plans.

President Obama today bypassed a stalled Congress to make a significant change in immigration policy, announcing he would stop the deportation of certain young undocumented immigrants by executive order. As New York Magazine put it: “Obama basically just passed the DREAM Act himself.”

The DREAM Act would create an opportunity for permanent residency for illegal aliens who meet certain requirements: They must have moved to the the United States before they turned 16 and be younger than 30, have been here for at least five continuous years, have no criminal history and pose no national security threat, and have graduated from a U.S. high school, earned a GED or been accepted into a post-secondary institution. The bill has been introduced in Congress each year since 2001.

Unlike the DREAM Act proposal, the president’s order would not grant legal status. Instead, immigrants who meet the eligibility requirements will be “immune from deportation.” The DREAM Act would allow students to apply for federal student loans, a provision that has won the bill many supporters among educators. But under Obama’s order, it seems likely that these students would still be on their own to pay for college.

Obama started off his week with a focus on education in his weekly address, in which he argued that the federal government should act to prevent more teacher layoffs. “When states struggle, it’s up to Congress to step in and help out,” Obama said. “In 2009 and in 2010, we provided aid to states to help keeps hundreds of thousands of teachers in the classroom. But we need to do more.”

The presumed Republican nominee, Mitt Romney, dove into education policy in late May, releasing a white paper about his education policies and delivering a speech covering much of the same ground. The hallmark of Romney’s plan is a proposed voucher-like system linking $25 billion in federal funds to low-income and special education students so they would be able to attend any school – traditional public, private or charter – in any zip code.

Voucher advocates often say low-performing schools, faced with competition from private schools, will force improvements in order to avoid losing students. But although some research has found benefits for the students who receive vouchers, skeptics have pointed out that there is little research to demonstrate that vouchers help public schools get better.

As the New York Times reported, even Margaret Spellings, former education secretary under George W. Bush and previously an informal adviser to Romney, has doubts about the plan. Spellings stopped advising Romney after he “rejected strong federal accountability measures” in his education proposal, according to the Times.

“I have long supported and defended and believed in a muscular federal role on school accountability,” Spellings told the Times. “Vouchers and choice as the drivers of accountability – obviously that’s untried and untested.”

Andy Rotherham, a columnist for Time, argues that Romney’s plan is hardly as revolutionary as the candidate has portrayed it. Rotherham described it as “puny,” adding: “This latest round of voucher-pseudonym talk probably won’t amount to much. That’s because school choice is a state-by-state game, not a federal one.”

Widespread dissatisfaction with new teacher evaluations in Tennessee

In many ways, Tennessee teachers have acted as guinea pigs in a new national movement to overhaul how teachers are evaluated. While many states are in the process of changing the measures used to gauge teacher effectiveness, Tennessee launched its system—which includes both classroom observations and student test-scores among the measures used to rate teachers—last school year.

Now, the results of a statewide survey show widespread dissatisfaction with how the system is working so far. The survey, conducted by the State Collaborative on Reforming Education (SCORE), a nonprofit advocacy group, included responses from 15,401 teachers (about 23 percent of the state total) and 932 principals and was part of a larger effort to gather feedback about the new system.

(See The Hechinger Report’s series on Tennessee’s new system here.)

Some of the key findings:

- While 28 percent of the teachers who responded said the system “gives me a much clearer understanding of my school’s expectations for effective teaching,” only 29 percent agreed that the evaluations “will have a positive impact on my own teaching practice.”

- Nearly half of teacher respondents said they didn’t think they could fit all of the requirements of the classroom observation measure—a major component of the evaluation rating—into the timeframe allowed. At the same time, a third of principals said the timeframe (about 15 minutes per observation), was insufficient to cover all of the requirements.

- About a quarter of teachers expressed doubts about whether their evaluators could assess them accurately and consistently.

- More than a third said they weren’t confident that the student-achievement measures used to rate them were accurate reflections of how their effectiveness in the classroom.

- Teachers in low-performing districts were the most disgruntled about the new system, according to SCORE officials. “Many do not believe in the value of the evaluation system,” said Sharon Roberts, SCORE’s chief operating officer and a former school superintendent, during a webinar presenting the report on Monday.

- Principals, on the other hand, were more likely to favor the system. Seventy-six percent agreed that the system “will have a positive impact on instruction in my school.”

Teacher buy-in is critical, of course, in ensuring that the new evaluation systems actually transform teaching and learning. The primary purpose of the system is to “identify and support instruction that will lead to high levels of student achievement,” said Jamie Woodson, SCORE’s president and CEO.

The organization, which supports the new evaluation system, has several recommendations for the state. The most specific is a call for the state to change the weighting of measures for teachers of subjects that don’t have standardized tests. Such teachers make up two-thirds of Tennessee’s teaching force. Under the current system, those teachers receive ratings based on school-wide test-scores. That is, their ratings are based largely on how students perform on standardized tests in other teachers’ classes.

The report suggests that the state consider increasing the weighting of qualitative measures in these teachers’ ratings, at least temporarily, rather than placing so much emphasis on standardized test-scores.

In addition, SCORE recommends that the state give more training to teachers and principals in the new evaluation system, provide more training opportunities for teachers linked to the feedback in their evaluations, and that school leaders also be held accountable through their own evaluation system.

Parents protest Pearson, New York state’s ‘field-testing’ of exams

Over 300 parents and their children gathered outside the New York City office of testing-giant Pearson Education this morning, June 7th, to protest the company’s field-testing of exams in elementary and middle schools across New York state.

Students in the Empire State took a new, longer standardized exam this spring as part of the state’s five-year, $32 million contract with Pearson. The contract mandates field-testing, which is the common practice of testing questions out on students before using them on actual exams.

Students in the Empire State took a new, longer standardized exam this spring as part of the state’s five-year, $32 million contract with Pearson. The contract mandates field-testing, which is the common practice of testing questions out on students before using them on actual exams.

That hasn’t sat well with some parents, especially in the wake of recent criticism of Pearson, after it was revealed in April that one of its tests included a seemingly nonsensical passage about a talking pineapple.

“Our kids should not be their guinea pigs to test their tests,” said Jayne Wexler, a mother who attended the protest with her third-grade son Justice. “Our kids just went through six days of really hard testing and months of preparation. Let them compensate people to do it, or find a better way.”

The protest included puppets representing New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg; Chancellor of the State Board of Regents, Merryl H. Tisch; and New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo.

The protest included puppets representing New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg; Chancellor of the State Board of Regents, Merryl H. Tisch; and New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo.

Study looks ‘under the hood’ of new teacher-evaluation systems

More and more states are adopting new teacher-evaluation systems in response to a growing consensus that improved teacher quality can spell improved student achievement. The idea is that measuring how teachers perform in the classroom will help schools take the first steps toward helping them get better. But so far, there’s little consensus on the best ways to make those measurements.

Many states are moving quickly to launch new systems—in some cases, without much thought or work to ensure that the methods are sound. One teacher evaluation expert, Charlotte Danielson, has warned of a wave of lawsuits in places that don’t proceed with extreme caution.

A new report out today looks at the early adopters of new teacher-evaluation systems—and how they differ—as a way to help states and districts consider both innovations and potential missteps. The report, “Measuring Teacher Effectiveness: A Look ‘Under the Hood’ of Teacher Evaluation in 10 Sites,” was commissioned by ConnCAN, 50CAN and Public Impact, all education advocacy groups that support overhauling how teachers have been evaluated historically.

While most states and districts have agreed to use multiple ways to rate teachers—including, usually, a combination of classroom observations and student test-scores—from there they often diverge.

The use of standardized test-scores to evaluate teachers has received a great deal of attention, but one of the bigger challenges that states and districts face is how to rate teachers whose students don’t take such tests. In most school systems, the vast majority of teachers—up to 88 percent, for instance, in the District of Columbia—do not teach subjects or grade-levels covered by standardized tests. The study found that the early adopters have come up with different ways to measure how the students of these teachers are progressing. In some instances, districts are simply adding more standardized tests. Elsewhere, teachers will be graded based on portfolios or teacher-created assessments.

In several cases, more than one measure looking at how a teacher has affected students is being taken into account. “The rationale is that no single measure is perfect, but combining multiple measures diminishes the weaknesses of any particular measure,” the report’s authors say.

Daniela Doyle and Jiye Grace Han of Public Impact, who co-wrote the report, also found differences in how student “growth” on standardized tests is measured; some of the more esoteric details of the calculations have been hotly debated among researchers.

When it comes to classroom observations, “there was a surprising amount of consensus,” according to Doyle and Han. But leaders of the various sites studied in their report made different decisions about who conducts the observations and how often they occur. (In our own reporting on efforts to overhaul teacher evaluations, we have found nuances among different systems that do seem to matter.)

“Measuring Teacher Effectiveness” doesn’t endorse any particular method: “None of these systems claims to have cracked the code for teacher evaluation,” the authors write. Instead, they focus on in-depth comparisons. What might seem like so many insignificant details to outside observers will loom large for the teachers and students they’re meant to help.

Fact-checking Romney’s claims in his education speech this week

Likely Republican presidential nominee Mitt Romney focused on education this week, releasing a 35-page plan outlining his education platform and giving a speech on education to the Latino Coalition of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce on Wednesday. Below, we scrutinize some of Romney’s claims.

Statement:

“Among developed countries, the United States comes in 14th of 34 in reading, 17th of 34 in science, and an abysmal 25th out of 34 in math.”

The Facts: Needs more context

Romney was referring to the results of the 2009 Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), which was given to 15-year-olds around the globe. The United States’ performance is often cited by politicians, including President Barack Obama, as an indicator that the country’s education system is doing poorly. But the results may not be so black and white, according to a summary of the results by the National Center for Education Statistics. In reading, for instance, although the United States was ranked 14th among Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, only six countries had scores that were significantly higher than that of the U.S. The remaining seven countries ranked ahead of us had scores that, statistically speaking, were indistinguishable from America’s. In science, though, 12 OECD countries had scores that were measurably higher, and in math that number was 17. Out of the 64 countries that took part in the assessment, nine had significantly higher average scores in reading, 18 in science and 23 in math.

Statement:

“After three months, students [in Washington, D.C.’s Opportunity Scholarship Program] could already read at levels 19 months ahead of their public-school peers.”

The Facts: It takes years, not months

The Opportunity Scholarship Program (OSP), started in 2004, allows students in Washington, D.C. to apply for scholarships to cover private-school tuition. The Obama administration has repeatedly tried to cut funding for the program—something Romney opposes. Romney’s claim here is off by a factor of 12; it actually took three years for students to make the gains he was speaking about. A 2009 study by the U.S. Department of Education showed that one group of students—those enrolled in the program for three years—had the equivalent of 14 to 19 months of extra learning in reading compared to their public-school peers. For students enrolled for shorter periods of time, the gains ranged from three to five months of extra learning. And as for math performance, there was no significant difference among program participants and their public-school peers. A 2010 study concluded that there was no “evidence that the OSP affected student achievement. On average, after at least four years students who were offered (or used) scholarships had reading and math test scores that were statistically similar to those who were not offered scholarships.” The same study did find, however, that students who received the scholarships were more likely than non-recipients to graduate from high school.

Statement:

“The two major teachers unions take in $600 million each year. That’s more revenue than both of the political parties combined. In 2008, the National Education Association spent more money on campaigns than any other organization in the country. And 90 percent of those funds went to Democrats.”

The Facts: Numbers may be off a bit

It’s difficult to quantify how much the National Education Association (NEA) and American Federation of Teachers (AFT) take in annually—each has many state and local affiliates that file their own 990 forms. In 2010, the NEA reported over $352 million in revenue on its tax filings. The AFT brought in $162.7 million. Historically, both organizations have had a large political presence and have favored Democratic candidates. According to OpenSecrets.org, which labels the political action committees (PACs) of both unions as “heavy hitters,” the NEA did top the list of national donors in 2007-2008, spending $56,228,408. The bulk of this money—$53.5 million—was spent at the state level, and about $36.7 million of it went to specific ballot initiatives rather than particular candidates. In 2008, the NEA’s PAC gave 91 percent of its money to Democrats. When it comes to total NEA donations, however—including to other PACs, as well as to candidates from both parties—Romney was slightly off: 86 percent of the NEA’s money went to Democrats.