After five tries in five years, Mississippi expands charters

Lawmakers in Mississippi passed legislation on Wednesday that will expand charter schools in the state, a victory for supporters who have made five attempts in five years to change the state’s current charter school law.

The bill would allow the publicly-funded, privately-run schools to open in low-performing districts, and would give school boards in high-performing districts the power to approve or veto charter applications in their area. A 2010 state law in Mississippi makes it possible for failing schools to be converted to charter schools if more than 50 percent of parents vote in favor of the conversion. Although schools were permitted to start converting in the 2012-13 school year, none of the 35 failing schools that are eligible ever made the attempt.

Charter schools have been a contentious topic in the state for years, igniting debates over race and poverty and creating sharp divides amongst lawmakers. While supporters say increased school choice could improve education in a state with some of the lowest test scores in the nation, opponents fear charters will only reach a small number of students and could further segregate state schools.

“We are doing this at a time when we are failing to properly fund our public schools,” said Senator Hob Bryan on Wednesday to members of the Senate, referring to the fact that Mississippi has only fully funded its school system twice since 2002. Bryan, who voted against the bill, also expressed concern that charter schools would be able to cherry pick students, potentially leaving more difficult students in public schools.

The legislation passed Wednesday will allow up to 15 charter schools to open in Mississippi, with the application process beginning in December. Original provisions that would have allowed for-profit companies and virtual charter schools were removed from the final version of the bill. Schools would be up for renewal every five years, with those failing to demonstrate adequate performance subject to shorter renewal terms. A provision in the bill allows for up to 25 percent of a charter school’s staff to be exempt from Mississippi teacher certification standards. However, these teachers must complete at least an alternative certification program within three years. Students would not be allowed to cross district lines to enroll in charters, a source of concern for some charter advocates.

Related stories

“This will have a damper effect on where charters can locate,” said Rachel Canter, executive director of the non-profit Mississippi First, who helped write the original bill last year. Since a charter school’s demographics must reflect those of the district where it resides, rural charters might struggle to attract a representative sample from a single district without having a large effect on that district’s enrollment numbers, Canter said.

Todd Ziebarth, vice president for state advocacy and support for the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools, says that although he wishes the legislation did not limit enrollment to students within each school’s district, the new law is a step in the right direction for Mississippi. “It makes some major improvements,” Ziebarth said. “For the first time, [it] will actually allow real charters in the state.” The alliance ranks charter laws annually, and Ziebarth says that Mississippi has always been ranked last out of the 43 states that have charter laws. “I don’t think they’ll be moving up to the top of the list,” Ziebarth said. “But I think they’re going to move far up.”

The charter school decision comes on the heels of Tuesday’s passage of a bill that will bring state funding to selected pre-k programs in Mississippi for the first time. Hours after the charter school bill was passed, the Senate also voted to pass a literacy bill that will hold most students back in third grade if they are not reading at grade level. Gov. Phil Bryant, who last year declared that education would be the focus of the 2013 legislative session, said in a statement Wednesday that he intends to sign the acts into laws.

Can we please change the conversation about college admissions?

If you’re spending any time in the company of ambitious high-school seniors or hyper-competitive parents these days, you may be reading Facebook posts with status updates proclaiming acceptances at prestigious colleges:

“Dartmouth! Duke! Vassar! Swag! I’m three for three!”

You may not read about rejections, but you will certainly hear plenty about them, along with much speculation about who got in and who didn’t—as well as some malicious gossip like, “I cannot believe Diana got into Yale and Stephen didn’t. Do you think she knew someone? His SAT scores were so much higher…”

Listen closely, and the list of rejected valedictorians, team captains and accomplished test-takers will go on and on. You may even hear navel-gazing parents and students who received too many thin envelopes ask themselves, “Where did we go wrong?”

We go wrong by engaging in this wrong-headed, waste-of-time conversation at all, and by comparing our kids’ test scores and GPAs, their merits and drawbacks. Sure, it’s seductive to be drawn into side-by-side comparisons and speculate about the “secret formula” for getting into top schools like Brown University, where 28,919 applicants vied for acceptances that totaled just 2,649.

In the new comedy Admission, the Princeton admissions officer played by Tina Fey is repeatedly asked to divulge that formula.

“Just be yourself,” Fey falsely answers. The film illustrates how largely unsuccessful such advice is by showing a parade of accomplished applicants falling through the floor of Princeton’s committee room and into oblivion.

“Just be yourself,” Fey falsely answers. The film illustrates how largely unsuccessful such advice is by showing a parade of accomplished applicants falling through the floor of Princeton’s committee room and into oblivion.

Unfortunately, the movie perpetuates Ivy League angst, promoting the wrong conversation in a country where community colleges enroll more than half of the students in higher education—and where the percentage of Americans between the ages of 25 and 64 with a two- or four-year college degree is just 38.7 percent.

College costs may be one reason. They’ve jumped 440 percent in the last 25 years—which is three times the rate of inflation. A year at Princeton costs $56,750. Two-thirds of students who graduated from a U.S. college in 2011 had loan debt, averaging $26,500 per borrower.

Listen to complaints about how many students are rejected from top schools with near-perfect SAT scores and it will be easy to ignore a more jarring statistic: scores on the exams used in college admissions have plummeted in recent years, suggesting that more students today are struggling with vocabulary, the meanings of words, sentence structure and math problems.

“When less than half of kids who want to go to college are prepared to do so, that system is failing,” former College Board president Gaston Caperton told The Washington Post last fall.

In reporting trips to schools in the impoverished state of Mississippi, I’ve been able to see up close the many challenges that keep higher education beyond the reach of the poor—and the poorly educated. Students there have the lowest ACT scores in the nation, averaging 18.7 points, which is well below the national mean of 21.1. The maximum score on the ACT is 36; many top colleges want to see scores of 30 or above.

You won’t see too many stories about it, though. Major media attention tends to focus on elite schools and who gets into Harvard, a topic I devoted years to covering as a higher-education reporter because editors insisted that readers find it fascinating.

The reporting reinforced my suspicion that there is almost nothing affluent parents with checkbooks at the ready won’t do—starting well before preschool—to give their progeny a leg up. That might mean hiring consultants who charge up to $40,000 to orchestrate college applications, or sending their teenagers off to a four-day application “boot camp” that costs $14,000.

Digging a little deeper, I learned a great deal from admissions deans like Harvard’s William Fitzsimmons, who never allowed me to sit in on committee discussions weighing the merits of applicants, but invited me to a meeting about how low-income students were faring at Harvard.

The answer? They often struggle mightily, a fact that elite college presidents have picked up on; some have spoken out about the need to attract more students who don’t come from affluent backgrounds and do more to make them feel comfortable.

The strategy sounds great, but low-income students with top grades and scores often don’t even apply to the most prestigious schools.

In fact, only a tiny fraction of students even consider applying to or attending elite institutions, according to Arthur Levine, former president of Teachers College, Columbia University, and now head of the Woodrow Wilson Foundation.

“A few years ago, I met a young woman who had been ostracized by her parents because she only got into Wesleyan, [the University of] Chicago and Swarthmore,” said Levine, adding that the problem is also a changing economy that requires postsecondary education.

“When four percent of the college-age population attended higher education in 1900, everyone shopped at Tiffany’s,” he said. “With more than 70 percent of high-school grads entering postsecondary education [now], it’s more like shopping at Walmart—so there is greater pressure to attend a university that marks or differentiates one from the Walmart shoppers.”

At The Hechinger Report, we focus on some of the more urgent issues in higher education, like college costs, access and completion. We’ve looked at schools that are doing a particularly good job at integrating students of color on campus, along with those who have work to do. We’ve questioned why some colleges may be misrepresenting admissions statistics, and tried to keep an eye on the obstacles in the way of President Barack Obama’s laudable goal of getting more Americans to earn college degrees.

We’ve also reported how a community-college degree can be lucrative—and that significant numbers of grads are getting better jobs and earning more at the start of their careers than those with bachelor’s degrees.

Beginning a new conversation about admissions is easier said than done, although I highly recommend the work of Lloyd Thacker at The Education Conservancy as a starting point. I’ve given a copy of his terrific book College Unranked: Ending the College Admissions Frenzy to many a friend and family member.

But as I contemplate the hundreds of thousands of dollars we may be shelling out to educate the teenagers in my family, I’ve also recommended The Neurotic Parent’s Guide to College Admissions: Strategies for Helicoptering, Hot-Housing & Micromanaging.

In his review of Admission, New York Times movie critic A.O. Scott notes that he is “the father of a high school junior, paying my tithe to the test prep gods while preparing to sacrifice most of my worldly goods on the altar of the liberal arts…”

Scott added: “How could anyone make light of the brutal, capricious system by which our young people are judged and sorted?”

People do so because the target is an easy one, and the conversation isn’t changing—though it should be.

I asked Thacker—who said he doesn’t plan to see Admission—for some ideas. His long list includes guidance for parents, teachers and students on how to change “the market-drenched admissions process,” which he says imperils qualities like curiosity and risk-taking by emphasizing “where a student goes to college over what a student does in college.”

Sounds like a good start to me.

Mississippi passes landmark pre-k bill, moves forward with charters

Mississippi is one step closer to passing sweeping education reforms that could, for the first time, bring state-funded pre-k to the state. On Wednesday, the House and Senate passed legislation that would provide $3 million to partially fund voluntary preschool programs for 4-year-olds beginning in the 2014-15 school year.

Advocates of early education in the state have been surprised by the state’s introduction, and subsequent passage, of pre-k legislation. Mississippi is the only state in the South—and one of 11 in the nation—that does not currently fund pre-k.

In December, Mississippi Gov. Phil Bryant released his budget proposal for the year, focusing heavily on education but leaving out funding for pre-k, except for a promising private program. Bryant has previously stated that he believes parents are responsible for educating their young children.

While the pre-k bill sailed through the House, the Senate debated the early education legislation, questioning the pre-k bill’s author, Sen. Brice Wiggins, about the effects the legislation would have on church programs and current pre-k teachers. The bill would raise the required qualifications of pre-k teachers and assistants, mandating that they have at least a bachelor’s degree or an associate degree, respectively.

During the debate, Wiggins reminded lawmakers that Mississippi is behind most states in passing preschool legislation, and encouraged skeptics to consider the benefits of pre-k. “ We don’t want [kids] to just be babysat,” Wiggins said, referring to the fact that about 85 percent of children in the state currently attend some form of day care or preschool in the state. “The idea is that if they’re going to be there, that we educate them,” he added.

Passage of the bill could have important implications for children in Mississippi. The state has a large and mostly unregulated system of day care and pre-k programs, and there is no guarantee of quality.

Related stories

The Hechinger Report has been taking an extended look at education in the state, with a focus on pre-k.

Research has shown that the first five years in a child’s life are the most critical for learning. Often, children who begin school unprepared and behind their peers never catch up. In Mississippi, one out of every 14 kindergarteners and one out of every 15 first-graders were deemed unprepared for the next grade-level, according to the Southern Education Foundation, costing the state over $2 billion between 1998 and 2008 in remediation costs.

The pre-k bill would offer matching funds during the first phase of the program to approved programs that can raise half of their program costs. To receive funding, school districts or licensed childcare and Head Start centers must meet a variety of requirements beyond those required to get licensed. Programs must adopt a research-based curriculum, serve at least one meal a day that meets national dietary requirements, and hire qualified teachers.

Some advocates worry that the bill will not actually serve the state’s neediest children. Unlike legislation in every other Southern state but Alabama, the bill does not prioritize giving seats to low-income children or those with limited English proficiency. And the process to get licensed can be challenging for daycare centers in rural areas that may struggle to raise half the funds, or that lack the capacity to handle the paperwork and demands of licensing.

“It’s going to benefit the communities that have the resources, and leave behind the communities that don’t have the resources,” Carol Burnett, founder and director of Mississippi’s Low-Income Child Care Initiative, told the Southern Education Desk.

The Senate is expected to vote today on a House-Senate agreement of a charter school bill, which passed the House on Tuesday. The bill would allow charter schools to open in low-performing districts, and give school boards in high-performing districts veto power over the schools. Some have expressed concern that, like the proposed pre-k legislation, this bill will not actually help the students most in need. They wouldn’t be allowed to cross district lines to attend charter schools, which could make it hard for schools to attract the numbers and types of students required by the bill.

Legislators are also expected to vote today on other bills backed by Gov. Bryant, including a teacher merit pay pilot program and a literacy bill that would keep most third-graders from advancing to fourth grade if they’re not reading at grade level.

—

When knowing everything about your students isn’t enough

In March, technology entrepreneurs, venture capitalists, representatives from big-name companies and philanthropies and some teachers descended on Austin, TX for a conference meant to highlight new solutions to the biggest dilemmas in education.

Educational games, apps, data dashboards and social media were touted as the next big things in panels with titles like “EdTech Entrepreneurs: Are They the Next Superheroes?” and “Building Schools Into the Innovation Ecosystem.” The main theme at the SXSWedu conference—which is linked to the better known music and technology festivals—was how these new technologies are poised to make the learning experience for students more “personalized.” With data gathered and organized by new software systems, games and apps, the idea is that teachers will know their students better than ever and be able to pinpoint exactly where they’ve gone off course and, the hope is, what they need to get back on track.

The panelists were passionate and people were excited.

“The market is going to be the best forum that’s going to solve the problems [of education]. Not government. Not NGOs,” said Stephen Coller, of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation during a panel about “Big Data” (The foundation is one of the many contributors to The Hechinger Report.)

Somewhat less well attended than the sessions devoted to tips on how to make a profit in the ed-tech sector was the screening of a documentary, “The New Public,” about a school in a high-poverty Brooklyn neighborhood, Bedford-Stuyvesant. The film, one of several that screened at the conference, held up a more complicated—and less certain—picture of what’s needed to solve some of education’s most intractable problems. The filmmaker, Jyllian Gunther, followed the lives of students, teachers and administrators as they launched a new high school, Brooklyn Community Arts & Media (BCAM), one of the hundreds of new small schools opened under Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s administration.

Like the technologies being promoted at SXSWedu, smaller schools were also meant to personalize the learning experience for students; the hope was that replacing large, comprehensive high schools with smaller school communities would make education more intimate and student-focused, and would help boost graduation rates. (Early on, the Gates Foundation helped fund the small school movement, but as research on the effectiveness of the reform came back mixed, the foundation abandoned the idea.)

Gunther’s cameras, including the ones students took home with them to film scenes with their parents and siblings, captured how difficult it is to get education right for the neediest students.

For the school leaders and teachers at BCAM, personalized learning didn’t involve apps or data dashboards. They took a less high-tech approach: getting to know the mostly African-American students and their families well during meetings and home visits, taking seriously their hopes and concerns about their own education (even letting students give input on punishments for peers who misbehave), and taking into account their culture and experiences outside school, including incorporating hip hop and dance into the curriculum and providing sessions on self-esteem for girls worried about their body image.

It was attention that the students had often found lacking in their previous schools. And yet it often wasn’t enough. Gunther returned to the school to check in on how the freshman she’d met four years earlier were faring their senior year. Many had left. Others who had once planned on college were struggling to make it to graduation at all. In a particularly heart-rending storyline, a once-buoyant student who wrestled with his sexual identity became more and more dejected as he received college rejection letters, one after the other.

In the fourth year, test prep became a more prominent feature of the school as teachers and administrators reflected that they should have put more emphasis on academic rigor—not just getting to know and engage their students. Perhaps some of the new technology coming down the pike could have helped them better juggle the balance between challenging, engaging and caring for their students.

The personalized learning that ed-tech pioneers are talking about now involves using data points like test scores, attendance and, perhaps someday, information about students gathered from games or their internet searches, to home in what students need academically. Maybe more high-tech systems and detailed data would have helped teachers recognize how far behind many students were on the path to graduation.

But would it have helped teachers figure out how to help a student deal with her rage issues so she could get over her frustrations in science class? Or how to keep a young student who was mocked for being gay at school and at home from losing hope and help him stay focused on his strengths? Or how to salvage the academic career of a student whose prospects once looked promising and who suddenly stopped caring about his future?

The film doesn’t make an argument for or against any particular reforms. Instead, the educators at BCAM discovered that even when you know nearly everything about a student, solutions to help them succeed can still be elusive.

Five Hechinger Report writers recognized with national awards

For the third consecutive year, The Hechinger Report has been honored with National Awards for Education writing from the Education Writers Association. Our brand of solutions-oriented, in-depth writing about education has been appearing in major publications across the U.S. since May 2010.

Sara Neufeld

Sarah Carr

Jon Marcus

Sarah Garland

Jill Barshay

Five Report writers are among the winners of the 2012 National Awards for Education Reporting, announced Tuesday by the Education Writers Association.

Sarah Carr won first prize for beat reporting, for stories covering k-12 education in the South. Carr’s stories, which span the topics of school choice, segregation, and teacher effectiveness in Mississippi and Louisiana, have been published by Time and The Atlantic.

Jon Marcus shared second prize in the same category, for comprehensive coverage of higher education. Marcus’s work frequently appears in Time, CNN Money and NBC News.

Sara Neufeld, a contributing writer for The Hechinger Report, was awarded a special citation for her collaboration with the NJ Spotlight and WNYC for “A Promise To Renew in Newark,” a series examining the turnaround attempts of a low-performing school in New Jersey.

Sarah Garland and Jill Barshay were also awarded a special citation for their investigative reporting project “Teaching the Teachers NYC,” a series with Beth Fertig of WNYC that examined the ongoing professional development of teachers in New York City.

The 62 winning entries, selected from hundreds of submissions, recognize the best education journalism produced by print, radio and online media outlets across the country.

Reaction to pricey LA school board elections: Many claims of victory

The Los Angeles school board election attracted enormous amounts of outside money and attention, so it’s no surprise that lots of people are claiming victory in the aftermath. In the end, an incumbent aligned with Supt. John Deasy and an incumbent supported by the teachers union each won, while a third candidate will be in a runoff.

The election attracted record donations, but the attention also created some resentment. Warren Fletcher, president of United Teachers Los Angeles, told Reuters he disliked that outside donations changed the tenor and focus of the race.

“This isn’t a national referendum,” he said. “It’s a local school board election. It’s about local issues.”

Many of those local issues are also being played out nationally, which is one reason why donors including Mayor Michael Bloomberg supported a slate of school-board candidates who believe in charter schools and in evaluating teachers based on student test performance – something the teachers union there has resisted.

Along with claims of victory, though, came some reality checks.

“How anticlimactic,’’ wrote blogger Alexander Russo. “In a showdown that’s fast approaching 2007’s $7 million campaign spending record, the teachers union and reform groups each succeeded in protecting one of their key supporters on the LAUSD School Board last night — but failed to score any decisive victory against the other side. ‘’

Here’s a quick snapshot of some reactions to the results:

Michelle Rhee, Students First founder and chief executive officer:

“Los Angeles voters made it clear that they stand together with those of us fighting to put kids first and who believe that every child deserves access to a world-class education. Last night’s outcome underscores the importance of the ongoing effort to elevate teaching, empower parents and implement reforms that are in the best interest of our students.”

Joe Williams and Gloria Romero, Democrats for Education Reform:

“Mónica García, the courageous LAUSD board president, held off her opponents to win reelection. Mónica faced multiple challengers in this election, precisely because she has demonstrated the courage to fight for reforms. Status quo forces mobilized in a big way, but so did the education reform community. We are thrilled that she will remain a bold voice on the LAUSD board.”

United Teachers of Los Angeles:

“UTLA is pleased that veteran teacher Steve Zimmer appears to have retained his seat on LAUSD’s Board of Education. Voters were not swayed by outsiders and their millions. School Board seats are not for sale. Zimmer has been a champion of students and an important voice on the school board.”

Arne Duncan stands firm: Sequester would squeeze schools

This post comes to us courtesy of Education Week’s Politics K-12 blog.

Today is the day that those automatic, across-the-board spending cuts that have been coming since August 2011 are finally set to kick in. And U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan has been a chief spokesman for the administration on the impact of the cuts on domestic programs—and landed in some pretty hot water with fact checkers.

Earlier this week, the White House put out job loss estimates, including for K-12 schools, and Duncan backed them up on Sunday’s political talk shows. However, it’s really too early to know exactly how many layoffs, furloughs, or programmatic cuts will result from sequestration (which would represent the largest cut to federal K-12 aid in recent history). School districts—not to mention states, and the federal government—are still hammering out their spending plans for this year. Schools don’t typically send out Reduction in Force (RIF) notices until March or April.

That means teachers won’t lose their positions this school year, although some districts are beginning to contemplate layoffs for next year, as well as cuts to things like professional development, according to this report by the American Association of School Administrators. Another survey by the organization, released last year, showed that many school districts were trying to carefully plan for the cuts, to minimize the impact on students and staff.

Besides, state and local money makes up the vast majority (about 90 percent) of a district’s budget, so school district officials could be watching their state legislatures just as closely (more closely?) than they are watching Congress when it comes to deciding just how many teaching positions they can fund next year.

Given all that, I asked Secretary Duncan earlier today, at an event at an elementary school in Takoma Park, Md., if he still stands by the estimates the White House put out earlier this week.

Here’s what he told me:

“Obviously all these potential cuts are not coming at a time when states and districts are flush. We lost a couple hundred thousand teacher jobs over the past few years.” And he said “the vast majority of [district] money goes to people. There simply aren’t too many other places to go.”

He added that districts have the option of furloughing teachers rather than laying them off, which he said would still be detrimental to kids. “If your money is going to people, people are going to get hurt. These are estimates, we’ll see, this is the potential impact. I think again, you’ll start to see over time now, these notices going out.”

I asked him if he was worried that by putting estimates out there, rather than waiting for hard and fast numbers, he had undermined the administration’s (and advocates’) arguments that the sequester could be very damaging for schools.

“My job is to be clear and straight and transparent,” Duncan said. “We’ve never said that this is what’s going to happen. …We’ve always said this is what might happen. And sadly, this is what might happen.” (On CBS’s Face the Nation Duncan said that there are “literally teachers now who are getting pink slips, who are getting notices that they can’t come back this fall.” School district officials: Have you sent those notes? Or do you typically wait until March or April before announcing layoffs?)

More background on the cuts: The pain won’t be felt evenly everywhere. Some states, like Connecticut, don’t rely very much on federal funding for education, while others, like New Mexico, count much more on the feds. But overall, state budgets are largely rebounding from the recent recession, Michael Griffith, a state budget guru, told my colleague Andrew Ujifusa of State EdWatch fame.

The impact of sequestration appears to be equally murky when it comes to the $8 billion Head Start program, which helps low-income families cover the cost of preschool. The cuts will be far more immediate here, although it’s unclear what impact that will have on children served.

Here’s the administration’s take:

“We have a situation where we’re looking at the possibility of 70,000 young children losing their access to Head Start and Early Head Start, with teachers being laid off and teaching assistants being laid off,” Health and Human Services Secretary Kathleen Sebelius said at a press conference today.

But, as with K-12, it sounds like local implementation could be key to how Head Start programs absorb the cuts. Kenneth Wolfe, a spokesman for HHS, told me this week that under the sequester, Head Start programs that don’t operate in the summer could either end their current school year earlier than planned, or delay the start of the next school year to save money. Year-round programs would likely decide not to fill openings after children age out, he added. And grantees could also cut transportation services to find savings, he said. Some Head Start students may have no other way of getting to their programs. All of those steps would have a major impact on Head Start kids and families, of course.

The cuts may not be in place for long anyway. In fact, Rep. John Kline, the chairman of the House education committee, is betting they’ll be replaced with a broader budget agreement, possibly this year.

Local school districts are new target of education reformers

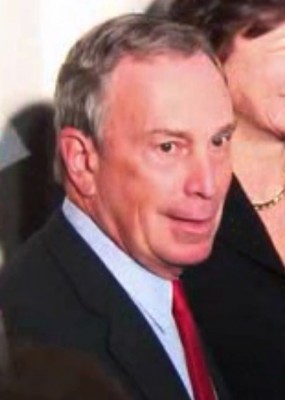

The large amounts of outside money flowing into the Los Angeles Unified school board election represent a new front in the reform battles that have shaken up education politics over the last decade. Donations of $1 million by Mayor Michael Bloomberg of New York City and $250,000 by former District of Columbia Public Schools Chancellor Michelle Rhee, in particular, have sparked controversy.

Billionaire Michael Bloomberg, New York City’s mayor, gave $1 million to some school-board candidates in Los Angeles. (Photo courtesy of Amanda Cogdon)

But the involvement of national school reform players in local district politics is a trend likely to accelerate now that would-be reformers have won major policy victories at the state and federal levels, experts and advocates say. Upcoming races in Denver and Newark, N.J., may be the next target for national groups like Rhee’s advocacy organization, StudentsFirst, and major donors like Bloomberg and his former school chancellor, Joel Klein, who has also contributed money to the Los Angeles race.

“A lot of the reform success started at the federal level with Race to the Top, it moved to states and now it’s very much in the implementation phase at the district level,” said Joe Williams, director of Democrats for Education Reform (DFER), an advocacy group that supports charter schools and teacher accountability. “How implementation is handled is important to a lot of people.”

In the case of Los Angeles, donors like Bloomberg, Rhee, and local philanthropists such as Eli Broad (who has been among the many funders of The Hechinger Report), are giving to a slate of school-board candidates who support charter schools, new teacher evaluations based on student test scores, and overhauling teacher tenure. Although Los Angeles is already piloting new evaluations to be launched next year, the teachers union has resisted the inclusion of test scores as a major factor in the rating system. (Student achievement measures will make up 30 percent of a teacher’s rating under a system negotiated this year with the union.)

Reformers are also concerned that the city’s charter schools might be adversely affected if the make-up of the school board becomes more union-friendly.

Outside participation in local education politics is not entirely a new phenomenon. National groups were involved in state races in last November’s elections, and national donors gave generously to candidates in last year’s school-board race in New Orleans. “The extent that you have Bloomberg giving a million dollars, that’s new,” said Sarah Reckhow, a political scientist at Michigan State University and author of Follow the Money: How Foundation Dollars Change Public School Politics. “But the base and the networks and the foundation for getting to this point [have] built over a couple of election cycles.”

A decade ago, fights for mayoral control of school districts—which took power out of the hands of many local school boards—also occasionally attracted outside involvement from national foundations or other advocates. “It’s where you don’t have mayoral control where you see the outside money going into the local school boards,” said Jeffrey Henig, a political scientist at Teachers College, Columbia University, who is beginning research on the involvement of national groups in local education politics. “In places where you don’t have the friendly mayor as your ally, this becomes a backup strategy.”

The local teachers union, United Teachers Los Angeles, has been among the most vocal opponents of the participation of large national donors in the race. The union is supporting a separate slate of candidates, including incumbent Steve Zimmer, who helped push through the new teacher evaluation system and who last year proposed a two-month moratorium on the approval of new charter schools. The measure was defeated.

Voters “do not need outsiders deciding who is best to sit on the LAUSD Board of Education,” Warren Fletcher, president of United Teachers Los Angeles, said in a statement quoted by the Los Angeles Times.

Henig says the increased outside involvement in local education politics could become a concern. “There are some legitimate questions about democracy and local community values,” he said. “In a lot of instances, the incumbents are not entrenched interests, they are responding to a constituency that elected them.”

Yet despite the attention the Los Angeles election is receiving, it’s unclear whether the outside cash will make much difference in the outcome of the races. The money from Bloomberg, Rhee and other donors is mostly going toward television commercials. In an off-year school board election that will likely turn out few voters, Reckhow said knocking on doors is usually a better strategy.

And the involvement of wealthy outsiders could create a backlash, Williams of DFER said: “The money could also be what tanks a candidate, if that’s what the storyline is with voters.”

Teacher job satisfaction at 25-year low

Job satisfaction among public school principals and teachers has decreased in the past five years, with teacher satisfaction reaching its lowest levels in 25 years, according to survey results released Thursday. Only 39 percent of teachers reported being very satisfied in their job, and more than half said they felt under “great stress” several days a week, the 29th annual MetLife Survey of the American Teacher found.

The findings come at a time when nearly every state around the country has adopted some sort of significant education reform in the past two years, including revising academic standards and implementing new teacher evaluation systems. Advocates say that many of these reforms, such as merit pay and the elimination of seniority-based layoffs, will help attract a higher-quality candidate to the profession.

But Michael Cohen, president of Achieve, a nonprofit group that promotes higher academic standards, said he was concerned by the job satisfaction numbers and what they said about the general public’s view of educators. “What struck me most,” he said during a conference call hosted by MetLife to discuss the findings, is that “they are operating in an environment of public discourse that is often focused on blame.”

The survey also found that three-quarters of principals said that their job was too complex. “We’re asking principals to do a lot more with – at best – the same, or fewer resources,” Mel Riddile, an associate director at the National Association of Secondary School Principals, said on the call. “They’re encountering a perfect storm of Common Core implementation, new teacher evaluations and state accountability systems.”

Both Riddile and Cohen stressed that full implementation of the Common Core State Standards, a new set of k-12 academic standards that 48 states have adopted, would be a huge shift for virtually all schools.

Ninety percent of principals and 93 percent of teachers reported that teachers in their schools had the skills necessary for implementing the new standards, according to the survey. They were less sure, however, of the impact Common Core would have. Just 22 percent of principals and 17 percent of teachers said they were very confident the standards would increase student performance.

“Different surveys produce different findings of how supportive teachers are of the standards,” Cohen said. “None of this is going to happen quickly. These are long term changes.”

Will Obama’s early childhood plan actually work? How?

Questions about how much President Barack Obama’s ambitious early childhood partnership plan will cost and how quality will be maintained emerged immediately on Thursday, soon after Obama delivered long-awaited details in Decatur, Ga.

President Barack Obama reaches to shake hands with a Member of Congress as he arrives to deliver the State of the Union address at the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C., Feb. 12, 2013. (Official White House Photo by Pete Souza)

“Study after study shows that the earlier a child begins learning, the better he or she does down the road,’’ Obama told an enthusiastic crowd after a visit to an early childhood learning center. “Let’s make it a national priority to give every child access to a high-quality early education. Let’s give our kids that chance.”

The plan calls for a guarantee of preschool for all four-year-olds who are at or below 200 percent of the poverty line. It would expand funding for childcare programs for infants and toddlers as well. And teachers would have to meet high quality standards, while earning salaries in line with K-12 teachers, according to reports.

The speech produced joy – and skepticism.

“President Obama is trying, against great odds, to do something for 4-year-olds,” noted New York Times columnist Gail Collins, who pointed out that other presidents have tried and failed, while “working parents of every economic level scramble madly to find quality programs for their preschoolers, while the waiting lines for poor families looking for subsidized programs stretch on into infinity.”

Yet advocates and educators who have been pushing hard for the president to tout a larger federal role in early education found plenty of reasons to cheer the initiative, which first came up during the president’s State of the Union speech on Tuesday.

“It represents a milestone achievement that begins to place the United States in a position comparable to the nations of whom we routinely compete with economically,’’ said Professor Sharon Lynn Kagan, co-director of the National Center for Children and Families at Teachers College, Columbia University. “We have not had services for three- and four-year-olds voluntarily available in the past. So I regard this as a real policy advance.”

The plan also calls for expanding home-visiting initiatives that would provide nurses, social workers and others to meet in the homes of at-risk families and connect them with assistance.

“Voluntary home-visiting matches parents with trained professionals to provide information and support during pregnancy and throughout their child’s first few years—a critical developmental period,” noted Libby Doggett, director of the Pew Charitable Trusts home-visiting campaign. “Quality, voluntary home-visiting leads to fewer children in social welfare, mental health, and juvenile corrections systems, with considerable cost savings for states.”

But how will it all work? Questions remain about the cost, which has not yet been specified. Estimates are as high as $10 billion to $15 billion a year or more. “The money, of course, is the sticking point,” noted a New York magazine story.

House Republicans, the story points out, “are not the sort of people who, when presented with evidence of a really promising public investment program, nod their heads and say, ‘Okay then!’”

That’s a point duly noted by Rep. John Kline (R-Minn.), chairman of the House Education and the Workforce Committee. “We can all agree on the importance of ensuring children have the foundation they need to succeed in school and in life,’’ Kline told Education Week. “However, before we spend more taxpayer dollars on new programs, we must first review what is and is not working in existing initiatives, such as Head Start.”

Jerlean Daniel, executive director of the National Association for the Education of Young Children, is among the advocates who noted that bipartisan support will be needed, as well as a focus on quality.

“When program providers and schools do not have the financial and other resources to hire skilled teachers, to purchase appropriate curricula and equipment, and meet other quality standards, we create conditions of achievement inequity for children and undermine a valuable workforce,” Daniel said in statement.

Many challenges lie ahead. States and the federal government, points out Lisa Guernsey of the Early Ed Watch blog, are going to “need to offer preschool programs that are good enough to make a real, lasting difference for young children.”