Charter schools: Public? Private? Does it matter?

Those who live and breathe education policy assume everyone knows what a “charter school” is. (Here is some history.) But polls show that most people haven’t a clue. Newspapers don’t help much. Sometimes they are said to be schools that are “publicly funded but privately operated.” Sometimes they are said to be “public schools that are less regulated.” Whatever they are, there are more than 5,000 of them enrolling more than 1.5 million students and in many cities there are long waiting lists. The Obama administration supports “good” charter schools, i.e. those that make a difference in the lives of kids, and is putting some money toward promoting their spread.

On the Gotham Schools site in New York City, a Teachers College graduate student named Alexander Hoffman parsed the terms “public school” and “charter school” and determined, in a tightly argued analysis, that charter schools are NOT public schools. (That’s the claim made by many opponents of charter schools.) One of his reasons is that charter schools “by design… are less responsive than traditional public schools….” I am sure that many parents of “public schools” wouldn’t give their schools high marks for responsiveness.

But here’s my question: why does it matter if they are public or private as long as students are getting a good education and are not being forced into religious instruction?

— Richard Lee Colvin

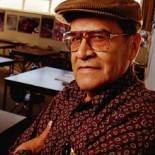

Jaime Escalante, an appreciation

As this report from NPR’s Claudio Sanchez makes clear, Jaime Escalante, the real teacher who inspired the movie Stand and Deliver, wanted to be remembered simply as a good teacher. Which, because he helped his students exceed their expectations, he was.

— Richard Lee Colvin

You gotta give to get

The first two winners of grants from the Obama administration’s $4 billion “Race to the Top” fund — Tennessee and Delaware — were announced yesterday and the decision ignited the education blogosphere. For those who don’t venture into that world much, it’s a surprisingly contentious, Alice-in-Wonderland place. Broken down, the debate went like this:

Both states had 100 percent participation of their school districts and near-unanimous backing of local teachers union leaders. In the auto or any other industry this would be seen as a good thing. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan took note of it. He was pleased, he said, that the $500 million bet being placed on Tennessee and the $100 million wager laid down in Delaware would benefit 100 percent of the students in both states. The fact that the unions representing classroom teachers — as well as philanthropists, business leaders and political leaders of both parties — were on board also was seen as a plus.

But education conservatives, led by the ever-entertaining and often-brilliant Rick Hess ![]() of the American Enterprise Institute, were skeptical. (Full disclosure: Rick is on the advisory committee of The Hechinger Report.) He simply didn’t believe that school districts would “sign on to efforts to dramatically retool K-12 schooling.”

of the American Enterprise Institute, were skeptical. (Full disclosure: Rick is on the advisory committee of The Hechinger Report.) He simply didn’t believe that school districts would “sign on to efforts to dramatically retool K-12 schooling.”

Never mind that they did. So, they signed on to it but, when push comes to shove, they would resist? As my friends in Delaware have said, it’s a small state. It’s the kind of place where, when someone says “I know where you live,” they’re not kidding. The calculus seems to be that anything that’s popular can’t be serious. To be serious, you have to get people angry. On the other hand, the unions shouldn’t overplay their hand.

It’s probably not a good idea for them to stand in the way of their state receiving hundreds of millions of dollars in new money. You gotta give to get in this world.

— Richard Lee Colvin

Journalists race to cover “Race to Top”

U.S. Education Secretary Arne Duncan moved up an expected April 1st announcement of Race to the Top winners, and journalists scrambled to get the story. It appears the news that only Delaware and Tennessee received grants first appeared on the website of the Wall Street Journal.

The Washington Post quickly followed, with an initial story noting that the announcement was made via Twitter, where a stream of updates followed throughout the day.

Coverage is now likely to be focused on a mad scramble to get grants for the next round. As Duncan pointed out in a call with journalists, the U.S. Department of Education still has about $3.4 billion available for the second phase of the Race to the Top competition.

“We set a very high bar for the first phase,” Duncan said. “With $3.4 billion still available, we’re providing plenty of opportunity for all other states to develop plans and aggressively pursue reform.”

And for journalists to aggressively pursue what the states may need to do to get there.

— Liz Willen

The final nail in NCLB’s coffin?

Pundits aplenty are busy parsing the latest NAEP results. On Wednesday, the federal government released reading scores on the “nation’s report card” — also known as the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) — for fourth- and eighth-graders around the country.

The results disappointed almost everyone. Over at The Washington Post, Jay Mathews said the latest scores “can be read as an epitaph for No Child Left Behind” (NCLB). He also noted that the state with the most encouraging results, Kentucky, offered no real explanation for its success in a column by his Post colleagues Nick Anderson and Bill Turque: “Desperate for something to say with no new initiative to promote, the Kentucky education department spokeswoman decided to belabor the obvious: ‘It’s our teachers,’ she said. That is true, of course, but it really doesn’t give us much to argue about, so it’s a big disappointment.”

But elsewhere online, in Catherine Gewertz’s Ed Week coverage, Kentucky is revealed to be doing things, however small, that might actually matter: “Terry K. Holliday, Kentucky’s commissioner of education, attributed the gains to Reading First and to multiple state reading initiatives focusing on elementary and middle school. Reading coaches were dispatched to many schools to work with teachers, he said, and professional development in reading instruction was provided not just to English/language arts teachers, but to those in other subjects as well.”

This last point should not be overlooked: if my time teaching English at the middle and high school levels convinced me of anything, it was that most teachers don’t consider themselves responsible for the reading and writing skills of their students. Many teachers seem to think that it is the English teacher’s duty alone to teach reading and writing. But how flawed this mentality is!

One consequence of this mentality is that students are often not taught how to read historical or scientific texts — it is assumed, wrongly, that they know how to do so simply because they know how to read English — and this is hugely problematic. The same holds for writing: students need to be taught how to write in each discipline. Writing about a poem or novel is different than writing about Napoleon or the Big Bang.

In fact, every teacher is a teacher of reading and writing — most just don’t think of themselves in this way. This failure, I believe, is a plausible partial explanation for our nation’s woeful NAEP scores in reading. So, in providing professional development in reading instruction to all teachers, Kentucky is quite possibly onto something of great importance.

On a final note, D.C. Schools Chancellor Michelle Rhee is perhaps the only one jumping for joy at the recent NAEP results. Anderson and Turque of The Washington Post captured Rhee’s excitement over her district’s results: “‘We’re very heartened by this,’ Rhee said. ‘It’s hard to discount the fact that D.C. has never seen gains like this before relative to other jurisdictions.’ ”

Jay Mathews of the Post says the D.C. results virtually guarantee Rhee will hold onto her job as D.C. Schools Chancellor for at least the next year or two. I’m not so sure. When you’re at the very bottom — as Washington, D.C. is on most meaningful measures — there’s room for nothing but improvement.

Journalists to share community college coverage

The third and final class of Hechinger Community College fellows will be back in New York City this weekend to present their projects, as part of the Institute’s “Covering America, Covering Community Colleges” Fellowship.

So far, 40 journalists have been trained to take on a topic that is vastly undercovered at most U.S. news outlets.

Community college stories weren’t in the news much when this fellowship started and reporters often told us their editors weren’t terribly interested in the topic.

Since that time, President Barack Obama has elevated their importance in a recession economy as he pushes for more Americans to obtain degrees. Community colleges are in the news constantly, in many cases for closing their doors because so many students are turning to them (both for job re-training after layoffs and because they cost far less than other options).

In the first year, Matt Krupnick of the Contra Costa Times won a special citation from the Education Writers Association for a four-part series on California’s community colleges and the difficulty students have to transfer out of them.

Rita Giordano of the Philadelphia Inquirer was a finalist for the Mike Berger award for her series on the struggling students at the Community College of Philadelphia.

Rob Chaney was honored in the “best of the west,’’ contest for his extensive package on the role tribal colleges played in preserving Native American history and heritage

Tom Marshall of the St. Pete Times was honored with an EWA citation for his terrific “Doctors in Exile’’ series.

Camille Esch won a second place magazine award from EWA for “Higher Ed’s Bermuda Triangle,” which ran in the Washington Monthly.

Beth Fertig of WNYC took second place for her “adding it up’’ series on LaGuardia Community College. (Listen to the first installment below.)

April Dembosky took a look at rare look at the world of community college sports, examining how California’s community college athletic programs are faring in the state’s fiscal squeeze, from budget cuts and gender equity to recruitment of and access for minority students. Her stories appeared in the Sacramento Bee and on the California Report. (Listen to the audio below.)

Marisa Schultz of the Detroit News looked at how the economically devastated state of Michigan is retraining its jobless and what role higher education plays.

Jennifer Jordan of the Providence Journal is looking at how Rhode Island’s community college system is faring in an economic downturn and how it is preparing students for jobs of the future.

Brian Maffly of the Salt Lake Tribune looked at the implications of the decline or loss of Utah’s rural community colleges.

Bill Maxwell of the St. Petersburg Times is looking at collaborations between community colleges and public school districts that are aimed at reducing the number of students who need remediation in college.

Stephanie Cohen of Marketwatch is looking at how community colleges are using federal stimulus funds to train students for green jobs.

Elaine Korry looked at how private for-profit colleges are luring students shut out of community colleges, especially in nursing. (Listen to the audio below.)