Pay for performance? Try pay for acceptance

It’s harder to get into U.S. community colleges these days, as the newly unemployed seek job training and others felled by higher prices at four-year state schools or private institutions decide they’d rather stay local and pay less. That means longer waiting lists and students shut out of classes they need. So what’s an overtaxed community college to do?

Charge more.

Bristol Community College in Massachusetts will soon allow students to bypass waiting lists if they are willing to pay double the tuition, according to a story on TheBostonChannel. The idea is aimed at healthcare workers and comes as the school is partnering with the for-profit Princeton Review, which is investing in the school. The Review is planning to provide more space for students to take labs and other courses near the school.

The idea is not without some controversy.

According to TheBostonChannel, the head of the state’s community college council has complained that allowing students to pay more goes against the idea of public education.

— Liz Willen

Paying kids for performance?

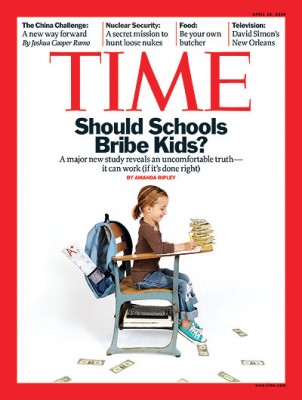

Time Magazine Cover (April 19, 2010 Issue)

The current issue of Time magazine features a cover story entitled “Should Schools Bribe Kids?” Amanda Ripley reports on a contentious study by a Harvard professor about how incentives influence student performance — but with a twist. Instead of paying teachers more for improved student performance, the idea in this study was to pay students for anything from showing up to school on time and wearing the proper uniform to behaving well in class and acing standardized tests.

The study was led by Harvard economist Roland Fryer, Jr., a scholar who shot to fame two years ago by becoming the youngest African American ever tenured by Harvard (at age 30). Fryer’s groundbreaking work into the black-white achievement gap and the phenomenon of “acting white” gained a national audience when it was reported on in the 2005 bestseller Freakonomics: A Rogue Economist Explores the Hidden Side of Everything.

(On a side note, I find it troubling that Time chose to feature a white girl on its cover when the story itself is about African-American and Latino students from low-income families. In fact, the five photos of students that accompany the story have only African-American faces. So why not an African-American student on the cover?)

What’s interesting about the study are the very mixed results. Experiments ran in four cities — Chicago, Dallas, New York City and Washington, D.C. — but only the Dallas and Washington, D.C. experiments seem to have “worked” in that important student outcomes improved.

The Dallas experiment was by far the cheapest and most basic, as well as the most successful. In it, second-graders from 22 different schools were paid $2 for each book they read. Students who received this money had significantly stronger reading comprehension scores when tested later in the year than students in a control group who received no such incentive. Ripley reports that “the experiment had as big or bigger an effect on learning as many other reforms that have been tested, like lowering class size or enrolling kids in Head Start early-education programs (both of which cost thousands of dollars more per student). And the experiment also boosted kids’ grades.”

I’m partial to the Dallas experiment because I used to do a very similar thing when I taught middle school. To make it seem less like I was bribing my students, however, I would give out lottery tickets for quarterly drawings. Students could earn lottery tickets by doing well on tests, helping out in the classroom, being a good Samaritan, and reading books, among other things. The vast majority of the lottery tickets I gave out went to students who read books in their free time, and so those who won the prizes — candy, gift certificates to the local mall, framed photographs and even books — tended to be the voracious readers in my classroom. I required students to fill out a form on each book they read and have a parent sign off on the fact that the student had actually read the book. Some of my students would read 200 books a year! (And, yes, I did have guidelines about what counted and what didn’t. Books had to be at least 75 pages long and of an appropriate reading level for the student.)

I found this a cost-effective way to promote reading and good behavior in my classroom, though of course I was paying for the prizes out of my own pocket. Fryer’s experiment, by contrast, was funded largely by private donations to the tune of $6.3 million. (If you do the math, that’s $350 per child for the 18,000 students in the study — not exactly cheap for something that appears not to have made much difference in two of the four experiments.)

To be sustainable, any future program that would seek to motivate students with money shouldn’t rely on private funders. Though the idea of giving hard, cold cash to students is anathema to many — it’s nothing short of bribery, critics claim — Fryer’s study suggests it might well be a cost-effective way to encourage positive behaviors, especially among elementary students.

Lessons from an auto assembly plant

End of the line for NUMMI

I just listened to the recent “This American Life” podcast* that explored the rise and fall of the NUMMI auto assembly plant in Fremont, California and what it says about the auto industry. (In 1984, the then-dominant General Motors and the insurgent Toyota agreed to build cars together: Toyota would learn to adapt its renowned manufacturing/management/teamwork system to the American context and GM would learn how that system had allowed Toyota to efficiently build very high quality vehicles.)

I immediately recognized that the story had implications for education reform. So did John Thompson, commenting on the This Week in Education blog. In the podcast we learn that at Toyota plants the workers are organized in teams and each member bears the responsibility for quality. Team members are well-trained in the assembly process, each step of which is timed down to the second. We also learn that it took a visionary United Auto Workers leader to get his rank-and-file members to go along with the changes, which required that they give up seniority and work closely with managers in an atmosphere of trust.

Thompson thinks the lesson is that schools should give teachers more autonomy and independence. But I thought the lesson was that teachers should recognize that they are part of a team, that they all are responsible for making sure kids learn, and that union leaders should be more cooperative and work more closely with principals and superintendents and not negotiate down to the minute how long they are required to be at school. This goes both ways, of course. Trust is like that.

— Richard Lee Colvin

*You can download the podcast for free from iTunes or for 99 cents from the This American Life home page. You can also read an All Things Considered story about the plant’s history from back in March.

More, more, harder, harder

The Florida Legislature also sent to Gov. Charlie Crist a bill (SB4) requiring students graduating in 2012 to take four math courses (including Algebra II or its equivalent), and those graduating in 2013 to take three science classes (including biology, chemistry and physics) and pass new end-of-course exams in those subjects. That doesn’t necessarily mean students will learn more, of course.

— Richard Lee Colvin

Merit pay and end of tenure in Florida move ahead

The Florida Legislature has sent to Gov. Charlie Crist a bill that would put all teachers hired after July 1 on one-year contracts and not offer them tenure. Raises would be based on student achievement. The governor, who previously had said he supported the bill, now says he may not sign it.

— Richard Lee Colvin

Taking classes without learning much

Over the past 25 years, students have been required to pass more and more math, science, English, history, and foreign language classes to graduate from high school. Today’s sophomores in 10 states will have to take more math than did students who graduated five years earlier; nine states will require them to take more science. So, voila, they’ll know more math and science! Well, according to a recent study of increased science requirements in the Chicago Public Schools, maybe not.

The study looked at a 1997 policy requiring all students to take three years of science to graduate. Before the policy, most students took only one science class. After, 90 percent of students took three. But, most students passed those classes with Cs and Ds. And according to a co-author of the report, previous research has found that only students who get As and Bs in their classes learn very much. So, the bottom line is that, while almost all Chicago students are sitting through science classes, the number of students learning more science has gone up only marginally. It’s not a surprise, but we often forget that only students who show up mentally and physically actually learn much. Sitting in a room where teaching is going on is not the same as learning.

— Richard Lee Colvin

Your check is in the mail: A job or your tuition back?

Community college comes with job promise (photo by Ivan Tortuga)

In a state that has struggled with some of the highest unemployment rates in country, it’s hard to imagine that a community college degree might come with the promise of a job. Yet that’s exactly what a school in ailing Michigan has proposed, according to Time magazine.

At a time when many community colleges are oversubscribed and turning away prospective applicants, Lansing Community College wants more students. To get them, the school has guaranteed that anyone who takes a six-week course in particular subjects will get a tuition refund if they don’t get a job within a year.

The offer doesn’t stand for just anyone, though, nor does it take into account one of the most vexing issues facing community colleges — the struggle of unprepared students to get through academic courses without first passing remedial math and English. This offer is targeted and specific to jobs the school believes are in high demand: call-center specialists, pharmacy technicians, quality inspectors and computer machinists — jobs with pay rates ranging from $12.10 to $15.72 an hour.

Some have questioned the college’s sanity. And Time noted some interesting perspective on the idea, courtesy of Russ Whitehurst, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, who wasn’t terribly optimistic.

“If every community college in America did something like that, they’d all be broke,” he told Time. “They’d be refunding all their tuition.”

It will interesting to see what happens; will enrollment rise? But more importantly, will students get jobs or a check in the mail?

— Liz Willen

Big graduation problem looms in tiny Rhode Island

If a bar is set high, will students rise to meet it?

The question has to be on the mind of anyone watching the progress of students in Rhode Island as the state moves toward stringent new graduation requirements. The question is both fascinating and painful.

At least 10 districts in the state are finding out just how hard it is to make high schools more rigorous, as Jennifer Jordan of the Providence Journal reports.

The word “rigor” may be overused and misleading, but Rhode Island is struggling to make sure that no students graduate without being able to read, write and compute at a high school level. That doesn’t sound that hard, right?

And yet, it truly is. Former Education Commissioner Peter McWalters called it “hard, complicated and tedious work,” according to the story, and told teachers it could take years to ensure that what happens in the classroom is aligned with statewide standards for every grade.

The story does a good job of laying out the obstacles, which include making sure all students have access to the most demanding courses and that struggling readers also get the help they need.

Other states are trying to do what Rhode Island is doing, but according to different timetables. If Rhode Island can’t fix some of the obstacles, Jordan notes, at least 10 school districts may be unable to issue diplomas to students in 2012.

–Liz Willen

Different takes on Race to the Top: Will it work?

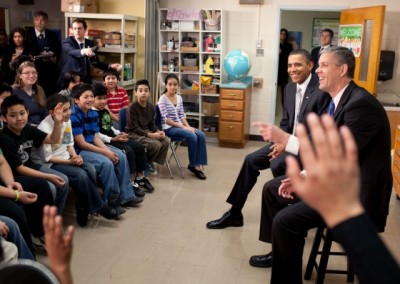

President Barack Obama and Secretary of Education Arne Duncan with Sixth-Graders in Virginia (courtesy of the White House)

Delaware and Tennessee have received competitive grants from the Obama administration’s Race to the Top competition, it’s interesting to see a variety of reactions about the program emerging. Always, there is plenty of blame to toss around in states that lost out. Winners and losers are still emerging as states gear up for the next awards in June.

Always, there are critics. For example, Rick Hess, the educator, political scientist and author of the Education Week blog Rick Hess Straight Up, says the program is a good idea, but the execution has been faulty.

“I think doing it through a competitive grant makes sense but I think the sum is large, the program is so novel, and the opportunities for getting it wrong are so great that it’s important to be incredibly thoughtful to get it right and I’m worried we’ve fallen short on that count,” Hess told the Ohio Gadfly.

Hess added that the program has not been buffered from politicians, and that the scoring “is based on hot fads of the moment and buzz words rather than knocking down outdated policies and anachronistic practice.”

Hess also said guidelines for spending and applications have been too vague.

The New York Times, on the other hand, praised the program in an editorial and proclaimed that it is already a success, noting that Race to the Top “already has had a huge, beneficial effect on the education reform effort, especially at the state and local levels.”

“The Race to the Top initiative won’t solve this country’s education problems by itself, but it is focusing attention on the right issues and moving them up the national agenda,” the editorial concludes.

— Liz Willen

Teachers, teachers everywhere — but not a job to take!

Newspapers around the country are reporting that would-be teachers aren’t having an easy time finding positions for the 2010-11 school year. The woeful economy and accompanying budget cuts have led many districts to freeze or significantly scale back on new hires. And yet there doesn’t appear to be any similar reduction in the number of teacher candidates entering the market.

In The Oregonian, Betsy Hammond tells the story of two aspiring teachers who have master’s degrees and substitute-teaching experience — but only bleak employment prospects. One has been on the market for almost two years, applying for over 100 jobs but not being offered even one of them. The other, with a background in mathematics and computer science, hasn’t been any luckier. It seems math vacancies have vanished. The relatively few specialities for which demand remains strong, at least in the Pacific Northwest, include special education, ESL and bilingual education.

Grace Merritt of The Hartford Courant reported on the sizeable drop in teacher vacancies in Connecticut, noting that the state currently suffers from a glut of elementary teachers, many of whom end up seeking work in other states. And yet urban areas in Connecticut continue to have openings they struggle to fill with qualified teachers. As in the Pacific Northwest, demand for teachers of special education and bilingual education remains robust.

What can teachers do to make themselves more marketable? One possibility is to increase the grade levels and/or subject areas that one is certified to teach. In Massachusetts, for instance, certified teachers can expand the subjects they are certified to teach simply by passing content-area tests. (Full disclosure: I am certified to teach history in Massachusetts — despite having taken no college courses in the field — simply because I paid $100 to take and pass a four-hour exam, and because I was already licensed by the state to teach another subject.)

Another option, especially attractive to younger teachers with fewer ties to particular cities or states, is to look abroad. International schools can be found on every continent but Antarctica, and the vast majority of them feature curricula taught in English. For teachers familiar with the Advanced Placement and International Baccalaureate curricula, a career in international school teaching shouldn’t be overlooked.