USA Today takes a look at our non-traditional students

In one of the more fascinating and misunderstood contradictions of the U.S. education system, nearly half of our college students are only part-time. Some 12 million (also almost half) attend community colleges and 38 percent are also working full-time. Only 56 percent of students at four-year colleges actually get a degree within six years.

Those numbers from the National Center for Education Statistics portray a very different college going population, at a time when President Barack Obama is pushing to rachet up the number of graduates. That’s why The Hechinger Report is intrigued with a project that will start running next week in USA Today that takes a look at some of the country’s non-traditional students Clearly, they now outnumber the now outdated image of a more traditional student going off college, living in a dorm and graduating four years later.

These students are parents and veterans, police officers and salesmen. You can watch some of their stories here: they will be running throughout next week.

Outliers — accounting for otherworldly achievement

Ever since reading Steven Pinker’s scathing review of Malcolm Gladwell’s latest efforts last November, I’ve hesitated to read Gladwell’s third book, Outliers: The Story of Success (2008). But as a teacher, I’ve always wondered about outliers. I’m curious less about why some of my students are so amazing and others aren’t – a phenomenon that can be explained simply by the law of averages – than about what characteristics are common among the superstar students. Is it genes? Is it work ethic? Is it passion, desire, devotion? In Gladwell’s account, otherworldly success turns out to be characterized by all of these things, and at least two more: opportunity and historical circumstance.

By historical circumstance, Gladwell means that some birth months or years can be more fortuitous than others. He explains how and why professional hockey players in Canada and the Czech Republic tend to be born in January, February and March – because January 1st cutoff dates among kids mean that those born earlier in a calendar year have a distinct advantage over those born later in the same year. (They’re bigger and more coordinated, two important qualities among athletes – and a six- or nine-month age difference among young children is huge.) Gladwell also explains how 1953-1956 were the ideal years in which to have been born for the computer revolution that took off in the mid-1970s: you wouldn’t be too old to have a family and established career, and you wouldn’t be too young to still be in middle or high school. As it turns out, Bill Gates, Paul Allen and Steve Ballmer (all of Microsoft fame), as well as Steve Jobs (Apple) and Eric Schmidt (Google), were all born between 1953 and 1956. Coincidence? Hardly, Gladwell says.

Citing the work of neurologist Daniel Levitin, Gladwell also writes about the so-called “10,000-Hour Rule,” the amount of time necessary to invest in something before mastery materializes on the horizon. The superstars of anything, Gladwell argues, get good by dint of their hard work – by outworking everyone else, and not just by a small margin. Passable pianists might practice an hour or two a day growing up, which is clearly a lot more than most people who dabble at the keyboard practice. But professional pianists – those who appear onstage at Carnegie Hall – start practicing five or six hours a day in their teenage years. They’re that good because they practice that much. (You can see why an hour a day won’t cut it at piano if there’s truth to the 10,000-hour rule: if you were to practice just one hour per day from the age of 3 – which is an overly optimistic estimate – you wouldn’t hit 10,000 hours until the age of 30. At that point, it’s far too late to begin making a name for yourself on stage. Mozart, remember, died at age 35, and Franz Schubert died at 31.)

Gladwell reminds his reader that “[h]ard work is a prison sentence only if it does not have meaning,” and he highlights three qualities of work that infuse it with meaning: “autonomy, complexity, and a connection between effort and reward.” If any of these three qualities is missing, it’s a safe bet the work won’t be particularly meaningful. In considering the current debates about linking teacher pay to student performance in the U.S., I’m struck by this last point – a connection between effort and reward. Too often in education, I think, teachers feel there isn’t much connection between the effort they invest and the rewards they reap (in terms of compensation or respect). But I suspect that many of the teachers who are wary of linking pay to performance – as I am, for reasons articulated elsewhere – would say that there are many rewards, mostly intangible, that directly result from the effort they invest. The unexpected “thank-you” note from a former student is my personal favorite.

This weekend I’ll blog about a former student of mine who is now starring in the Chicago production of Billy Elliot – he’s an outlier in just about every way, fluent in five languages and a master of both ballet and dance. Oh, and he’s only 12 years old!

Judging in the “Race to the Top” competition

The federal education department’s $4 billion “Race to the Top” competition received lots of attention from journalists and education policy types. Most federal education money is given to states and school districts using complex formulas that depend on factors such as population, poverty and political calculations. The Obama Administration was encouraged by Jon Schnur, one of its early education advisers, to shake that process up. The feds would describe the reforms they wanted states to undertake and states would use those as the criteria for applying for the money. Those that best met the criteria would win. Those that didn’t measure up would go without. But who would make that determination? The department appointed judges to read the applications and score them based on explicit criteria. Only two states–Delaware and Tennessee–won grants in the first round. States are gearing up to submit applications by June 1st for the second round.

Steven Brill, the journalist who founded American Lawyer magazine, touched on some of this in an analysis appearing in the upcoming New York Times Magazine. (Here’s a link to the HechingerEd post on this.) He also published a piece on EdWeek.0rg in which he analyzes the scoring process in greater depth. He raises a lot of questions about that pr0cess. Here’s a glimpse:

A review of the vetters’ score sheets and written comments juxtaposed against the applications they judged suggests that their standards were inconsistent, that some were naive about the difference between promises and the capacity to deliver, and that others fell victim to the propensity of many states to misstate the status of their programs and overstate the buy-in they had from key stakeholders, especially the teachers’ unions.

States have to submit their applications for a second round of the competition on June 1.

–Richard Lee Colvin

State of play: teacher unions and school reform

It’s well known that labor unions in general tend to support Democrats. It’s also well known that teachers unions, whose memberships make up one in four union members, are particularly supportive of Democrats. About one in 10 delegates to the Democratic Convention in 2008 were teacher union members. Democrats, of course, tend to favor more government spending on education. But, as this comprehensive analysis by Steven Brill in the upcoming New York Times magazine points out, President Obama and his education team have shown they are more aligned with reformers who focus more on results than on spending. This camp wants to change the basic rules of the education world, especially as they relate to teacher tenure, seniority, compensation, productivity, and charter schools.

There are gems of writing and reporting throughout this piece. Perhaps the most instructive is a passage in which Brill, the founder of the defunct American Lawyer magazine, describes two schools–one a charter school and one a traditional school–that each occupy half of a building in Harlem.

This is also a must-read for anyone who wants to get a sense of the forces at work in the school reform camp as well as those who want to better understand the $4 billion “Race to the Top” competition.

–Richard Lee Colvin

Unraveling the ban on “ethnic studies”

It’s been interesting watching the reaction to Arizona’s new ban on teaching ethnic studies, which comes after the state signed the toughest bill on immigration into law. With widespread protests over the immigration law ongoing, Republican Gov. Jan Brewer still managed to sign the ban into law last week.

Human rights experts have opposed the bill, which says schools cannot teach classes designed for students of a particular ethnic group, nor can they teach classes that promote the overthrow of the U.S. government. State Supt. of Public Instruction Tom Horne has said the bill was written to target a Chicano or Mexican-American studies program in the Tucson school district. Horne, who is running for attorney general, maintains that the classes promoted “a destructive ethnic chauvinism.”

School districts could have as much as 10 percent of their state funds withheld each month if they don’t comply with the law. They can also appeal the mandate, which goes into effect Dec. 31.

Support for Horne’s actions has been hard to find in editorials and in the blogosphere. In San Francisco, columinist Michael Yaki said it bears “the ugly stain of racism.” Valerie Strauss of the The Washington Post’s Answer Sheet calls the move “one small-minded bill that pretends to be about education but is all about politics.”

The Arizona Republic dislikes the ban, but in an editorial expressed deep concerns about the ethnic studies classes that have not been reported elsewhere. The editorial describes a local battle that might be more complicated than it first appears.

The Hechinger Report would like to know a bit more about the types of ethnic studies classes school districts are offering across the U.S. How are they being taught, and are they worthwhile? Are such classes typically integrated into a larger social studies or history curriculum? Are they worth defending? Are any other communities and school districts protesting these classes and, if so, why?

Pulling out all stops to win Race to the Top, Round Two

At 11:30 am this past Monday, I was slated to meet with John King, deputy commissioner of education for New York State, in midtown Manhattan.

At 10:40 am, his secretary called and canceled. Something important had unexpectedly come up, she said.

That “something” turned out to be a major agreement between the New York Department of Education and state teachers’ unions on how teachers are evaluated — and, more specifically, how student test scores fit into the picture. The New York Times reported on this big breakthrough yesterday, pointing out that the move was part of the state’s efforts to secure Race to the Top money in Round Two. New York could win up to $700 million in federal funds, although it finished a distant 15th out of 16 finalists in Round One.

Under the proposed system, which must still be approved by the state legislature, teachers would be categorized as “highly effective,” “effective,” “developing” or “ineffective.” (Currently, teachers in New York are rated only “satisfactory” or “unsatisfactory.”) Forty percent of teacher evaluations would depend on student test scores…but only, of course, for those teachers whose students take annual standardized exams. Most teachers’ students do not.

It’s now time for a semi-bold prediction: if this new system is implemented in New York, I’d be willing to bet that the vast majority of teachers will be rated “highly effective,” “effective” or “developing.”

In the past, criticism has been leveled against the binary rating system of “satisfactory” or “unsatisfactory,” in large part because 99 out of 100 teachers are rated “satisfactory.” The New Teacher Project’s widely cited 2009 report on this phenomenon, “The Widget Effect: Our National Failure to Acknowledge and Act on Differences in Teacher Effectiveness,” also found the following: “Districts that use a broader range of rating options do little better; in these districts, 94 percent of teachers receive one of the top two ratings and less than 1 percent are rated unsatisfactory.”

So don’t expect too much to change in terms of how many teachers are rated “ineffective.” It’s not likely to be much more than one percent. It might even be less — maybe half a percent.

I applaud New York’s decision to tie “only” 40 percent of teacher evaluations to student test scores — because, as the state commissioner and the chancellor of the State Board of Regents have acknowledged, New York’s current tests aren’t very good.

Teachers are often allergic to proposals that link their own performance to students’ test scores, and not without reason: many standardized tests are poor measures of true and meaningful learning. Most measure memorization. Most are highly predictable and easily gamed. This is, after all, why the multi-billion-dollar test-prep industry exists. Show me a good test and I’ll show you teachers unafraid of having evaluations tied to whether their students ace it. (The only tests I know that come close are part of the International Baccalaureate Diploma Program.)

For my take on why tying student test scores to teacher evaluations is highly problematic, see a commentary I wrote in February that appeared in Education Week. (Those who don’t subscribe to Education Week can access the entire piece here.)

Two worlds of education reform and improvement

Last week I was at the annual conference of the American Educational Research Association (AERA). There I heard lots of talk bemoaning social inequities and how they doom poor and minority kids to bleak futures. For many, the prescription seemed to be: fix society.

This week, I’m at the annual “summit” of the NewSchools Venture Fund. Just as its name suggests, NewSchools operates like a venture-capital fund. The Fund was started by two famed Silicon Valley venture-capitalists (John Doerr and Brook Byers) and Kim Smith, a pioneer of what’s called social entrepreneurship. Here, the prescription is:

1. Focus on results.

2. Put students first.

3. Have a sense of urgency.

4. Support entrepreneurial thinkers who want to bring new ideas to education.

In the AERA world, charter schools privatize education and take money away from “public schools.” In the NewSchools world, which invests in organizations that manage charter schools, people who share the dominant AERA view are “clueless,” because charter schools are public schools.

The dominant view of AERA folks is that low-income, Latino and African-American kids are harmed by the ideas of NewSchools. At NewSchools, the focus is on serving these students effectively and closing the achievement gap between them and white students. Such students account for 95 pecent of the enrollment in the charter schools supported by NewSchools. (All told, 1.5 million students attend 5,000 charter schools nationwide.)

It’s disorienting for one who isn’t a native of either of these worlds to visit each, one after another. Inside each world, the ideas seem to make sense. It’s certainly true that student outcomes are highly correlated with socioeconomic status. But the NewSchools folks challenge that truisim. As one NewSchools speaker said, “Great schools and great teaching can eradicate the effects of poverty in terms of student achievement.”

The NewSchools ideas seem to be in ascension. They provide the intellectual underpinning for many of the reforms being pushed by the Obama administration. In a message to the crowd of charter-school operators, entrepreneurs, foundation representatives and researchers, Secretary of Education Arne Duncan said: “The challenge before you now is to make these extraordinary successes a little less extraordinary and make them a little more ordinary.”

Should principals be trained like MBAs?

Teachers may be having a rough time lately, but it can’t be easy to be a principal in tough economic times either. With looming budget cuts and layoffs, school principals are having to make difficult decisions. They are also expected to be visionary instructional leaders as well, in the midst of a push for tougher graduation standards.

As a result, lots of school districts are experimenting with different ways of training principals, including programs that will teach them business skills similar to those learned in MBA programs.

In Indiana, for example, three universities hope to combine the best practices of business with education ideals, according to a story in the Associated Press. The idea is to install newly trained leaders in failing schools, but the concept has already met with some resistance.

“Principals don’t need more business; if anything, we need more training with our at-risk students that are more mobile, [or how to] deal with families that don’t value education,” Steve Baker, principal at Bluffton High School and incoming president of the Indiana Association of School Principals, told the Associated Press. “Those types of things, MBAs aren’t going to help me with.”

The idea isn’t a new one; Rice University in Texas launched a master’s of business administration program to prepare principals for Houston schools a few years back. And there’s been a lot of discussion about just how principals, who fill multiple roles, should be trained.

“School leaders often feel like the combined mayor, police chief and schoolmaster of a town with a population of 1,000 or more,” Jay Mathews of The Washington Post noted in one piece about the topic.

But will a business degree help?

Michigan to drop Algebra II requirement?

The Detroit Free Press had a short but interesting story on Friday about the state’s intention to drop Algebra II as a high school graduation requirement. Gov. Jennifer Granholm, a Democrat, has supported such a requirement in the past.

Some state legislators and educators fear it drives up the dropout rate, however, and thus they’d like to see the law amended so that students can opt-out of Algebra II with parental consent. The state senate overwhelmingly approved such a bill on Thursday, and it is now headed to Gov. Granholm’s desk.

The legislator leading the charge was Rep. Joel Sheltrown (D-West Branch), who according to the Free Press article would like to see “an alternative curriculum with such business-oriented math courses as statistics and data analysis.” I wonder, though, just what kind of statistics and data analysis Rep. Sheltrown has in mind — when done well, such courses are by no means easier than Algebra II. In fact, doing statistics and data analysis at a reasonably high level requires a solid grounding in mathematics.

There is definitely an argument to be made for high schools to offer courses in statistics and data analysis, both of which are relevant to our everyday lives and the judgments we make, but their apparent “easiness” is not among them.

Statistics is not for the faint of heart. And yet statistics is hugely important: how else can we decide whether it makes sense to pursue a given course of action? To buy a lottery ticket? (The odds of winning Powerball and MegaMillions are 1 in 195,249,054 and 1 in 175,711,536, respectively.) To believe a research study? To get screened early and often for certain cancers?

Speaking of statistics and cancer, Steven Strogatz recently wrote a blog post in The New York Times called “Chances Are” in which he retold a fascinating story from a book called Calculated Risks by the German cognitive psychologist Gerd Gigerenzer. It turns out most doctors aren’t very good at statistics. Here’s the story, as told by Strogatz:

“In one study, Gigerenzer and his colleagues asked doctors in Germany and the United States to estimate the probability that a woman with a positive mammogram actually has breast cancer, even though she’s in a low-risk group: 40 to 50 years old, with no symptoms or family history of breast cancer. To make the question specific, the doctors were told to assume the following statistics — couched in terms of percentages and probabilities — about the prevalence of breast cancer among women in this cohort, and also about the mammogram’s sensitivity and rate of false positives:

The probability that one of these women has breast cancer is 0.8 percent. If a woman has breast cancer, the probability is 90 percent that she will have a positive mammogram. If a woman does not have breast cancer, the probability is 7 percent that she will still have a positive mammogram. Imagine a woman who has a positive mammogram. What is the probability that she actually has breast cancer?”

Ninety-five out of 100 American doctors “estimated the woman’s probability of having breast cancer to be somewhere around 75 percent,” Strogatz reports.

The correct answer? Nine percent. This, my friends, is the power of statistics. If you’re dying to know why it’s nine rather than 75 percent, read Strogatz’s blog post.

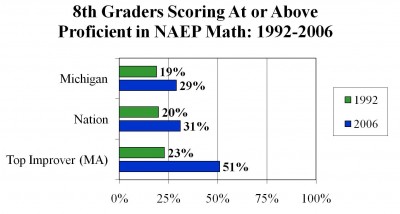

Returning to the case of Michigan and Algebra II, it’s worth noting that only 29 percent of the state’s eighth-graders scored at the “proficient” level on the 2006 National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP). This is an improvement from the 19 percent of Michigan eighth-graders who scored at the “proficient” level in 1992, but it’s far short of the 51 percent of Massachusetts eighth-graders who were deemed proficient in 2006.

Returning to the case of Michigan and Algebra II, it’s worth noting that only 29 percent of the state’s eighth-graders scored at the “proficient” level on the 2006 National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP). This is an improvement from the 19 percent of Michigan eighth-graders who scored at the “proficient” level in 1992, but it’s far short of the 51 percent of Massachusetts eighth-graders who were deemed proficient in 2006.

Michigan, like most states, is in desperate need of higher standards — a fact that a school board member quoted in the Free Press article realizes: “[W]e’ve got to have higher standards. We’ve got to have people ready for this type of thinking. The question is, how do we integrate that into the system?” Interestingly, the same school board member offers a very good answer to his own question: “I think the best approach is probably putting in some long-term demands so that we’re integrating this kind of learning right from Day 1, from elementary to middle school to high school.”

Yes, high standards need to be the norm, not the exception, and they need to be in place from the very beginning. There is even some evidence that suggests high standards can actually reduce rather than exacerbate the dropout problem.

Feds not a “silent partner” on education

The New York Times offered up a helpful primer this week on how Secretary of Education Arne Duncan thinks about the federal role in public education. Here’s an excerpt:

“In a speech last October, Mr. Duncan outlined his view of the proper federal role in education. He quoted President Lyndon B. Johnson, who funneled large amounts of federal money into public schools to help disadvantaged students, as saying Washington should be ‘a partner not a boss’ of local school authorities. Mr. Duncan added his own twist, though. ‘I’m not willing to be a silent partner,’ he said.

‘We’re not going to stand idly by where you have populations that are being poorly served, where we are in fact perpetuating poverty and social failure,’ he said last week in an interview in his office. ‘Our country can’t afford that.’

Washington should support reform, he said, by helping to set high standards, transform failing schools, reduce dropouts and increase college access.”