Tests as teacher-training tools: Two views from winners

U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan today announced the department’s picks for two plans to create new and improved tests to replace the fill-in-the-bubble versions that most states have long used. The grant competition was billed as a mini-Race to the Top, with only three contestants. The one loser was a smaller group of states proposing low-stakes high-school assessments; the two winners will split $330 million to develop their proposals for high-stakes and interim K-12 assessments.

The winning proposals are fairly similar. There’s a focus on performance assessments – tests in which students go beyond choosing answers from a multiple-choice list and produce things like essays, science experiments or speeches. One of the interesting — if subtle — distinctions, however, is how each proposes using the tests to improve teacher effectiveness.

In the SMARTER proposal — that’s the name, not my endorsement — the use of teachers as test-scorers is emphasized. Their proposal suggests that teacher- scoring is not only a way to get around the shortcomings of computer-scoring, but also a way to improve teaching.

In the SMARTER proposal — that’s the name, not my endorsement — the use of teachers as test-scorers is emphasized. Their proposal suggests that teacher- scoring is not only a way to get around the shortcomings of computer-scoring, but also a way to improve teaching.

As the SMARTER Balanced Assessment Consortium put it: “The Consortium recognizes and values the professional development opportunity inherent in the use of teacher scorers. We value teacher scoring because of its potential to help teachers internalize the performance standards and buy into the scoring process.”

The SMARTER proposal, which was submitted on behalf of 31 states and is 1,294 pages long, won less money from the U.S. Department of Education, although it has more states participating in it than the other winning consortium.

In the Partnership for Assessment of Readiness of College and Careers (PARCC) proposal, which won $170 million and received a higher score than the SMARTER proposal, states can choose whether to use teacher-scorers. Twenty-five states signed on to the PARCC proposal, including eight states that were also party to the SMARTER proposal. The PARCC consortium left some flexibility in its 1,609-page proposal because, in its words, “these assessments will be used for the purposes of teacher and school leader evaluations.” So the fear seems to be that tests scored by teachers might be less reliable since they know student scores could affect their job security.

SMARTER says it gets around this potential pitfall by saying it will require that teachers score only student work from other states.

And there’s a precedent, said Joe Willhoft, an assistant superintendent in the Washington public schools, the lead state in SMARTER: “Many states in our consortium have used teacher scoring in the past and it has been very successful.”

It’s also common overseas in high-performing countries, according to Linda Darling-Hammond, one of the advisers to the SMARTER consortium and an expert on performance-assessments. For an in-depth look at how it’s worked elsewhere, see this research series that Darling-Hammond headed up. (Disclosure: I did some copyediting for Stanford on several of the papers.)

Not that the PARCC consortium doesn’t see the tests as a way to increase both student achievement and teacher effectiveness. As Mitchell Chester, the Massachusetts schools commissioner said, these are the “twin goals” driving the creation of the new tests.

The two different proposals set up a potentially interesting experiment on how teaching might be improved by tests, though. One set of states (SMARTER) will go forward involving teachers more intimately in the process of testing, while the other (PARCC) will hold teachers more at arm’s length.

“We all know that teacher involvement is critical,” said Duncan’s chief of staff, Joanne Weiss. In the next few years – the tests are expected to go live in 2014-15 – we may be able to see how critical.

Recess round-up: September 2, 2010

A daily dose of education news around the nation – just in time for a little mid-day break!

Change agent: A profile of U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan. (Christian Science Monitor)

Improving assessments: The U.S. Department of Education awarded $330 million to two state-coalitions to design new assessment systems aligned with the Common Core Standards. (Education Week)

Teacher effectiveness: How to measure it? Read a June 2010 report from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation here.

Parent participation: Should parents be punished when their kids are chronically truant? (Sacramento Bee)

School incentives: How to get kids to go to school? Pay the parents. (St. Louis Today)

Teacher training: Just shy of Teach For America’s 20th anniversary, founder Wendy Kopp reflects on the past and looks toward the future. (The Wall Street Journal)

Charter schools and English language learners

Charter schools get a lot of accolades, but rarely are they touted for their work with English language learners (ELLs). That’s because in charter-school hot spots like New York City, charters have tended not to serve ELLs as much as they do other students, causing some groups to complain that they’re avoiding some of the most vulnerable and difficult-to-teach children.

In fact, 16.5 percent of charter students are English language learners, according to a new report by the Center for American Progress (CAP) and the National Council of La Raza (NCLR). Nationally, nine percent of schoolchildren in the U.S. don’t speak English at home.

Yet ELLs in charters tend to do much worse than their peers in regular public schools, the report’s authors note, citing one national study by Stanford researchers.

So what to do? The report, which is pegged to the Race to the Top competition and the flood of new charter schools it could unleash, says that “educators and policymakers certainly know more about what doesn’t work for Latino and ELL students and less about what does work.”

Perhaps — although one study by Pew that I often cite shows that English language learners do significantly better when they’re not isolated. As the study puts it: “When ELL students attended public schools with at least a minimum threshold number of white students, the gap between the math proficiency scores of white students and ELL students was considerably narrower.”

Diversity is also something that charters don’t always do well. But diversity may not be an option in places like the Rio Grande Valley in Texas, one of the poorest places in the country, where the student population is overwhelmingly Hispanic. (Forty percent of Latinos in the U.S. speak English as a second language.)

The report showcases four charters that appear to be doing quite well with ELLs. Two have student populations that are majority-ELLs. All four schools are majority-minority, meaning minorities make up the majority of the student body. CAP and NCLR hope these schools can point the way to success for other charters – let’s hope so!

Recess round-up: September 1, 2010

A daily dose of education news around the nation – just in time for a little mid-day break!

Back to school but staying home with virtual schools. (The Associated Press via The Boston Globe)

Comparing teachers: The conversation about how best to measure teacher-performance continues, especially when it comes to value-added models. (The New York Times)

Middle-schoolers: New York City students who attend kindergarten through eighth grade under one roof score higher on standardized tests than those who go to stand-alone middle schools. (The Wall Street Journal)

Pay-to-play: Sponsors of NBC’s Education Nation summit, to be held at the end of this month, include the Gates and Broad Foundations, Raytheon, Scholastic, American Airlines and the for-profit University of Phoenix. (Inside Higher Ed)

Special-ed: People who completed summer-long crash courses in teaching special education will enter classrooms in Milwaukee today. (The Hechinger Report, in collaboration with the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel)

Standardized tests: Thirty-nine percent of Oregon sophomores failed a state reading test required for graduation. (The Oregonian)

Waiting for Superman: Readers weigh in on Thomas Friedman’s August 25th column, “Steal This Movie, Too,” cautioning us on the film’s depiction of charter schools as a cure-all, and the roles of students, parents, teachers and school leaders. (The New York Times)

Recess round-up: August 31, 2010

A daily dose of education news around the nation – just in time for a little mid-day break!

Campaigns: John Hickenlooper, Democratic candidate for Colorado governor, supports funding schools based on student performance. And he wants to add more competition and school choice. (KRCC Public Radio for Southern Colorado and New Mexico)

Education reform: District officials in San Diego “rolled out a new improvement plan that is almost the opposite of its controversial predecessor,” the “Blueprint for Student Success.” (Education Week)

Early education: Giving and taking in California when it comes to the littlest learners. (Mercury News and Associated Press)

New Orleans at Five: Statistically, academic achievement in New Orleans hasn’t been correlated with reforms. One reporter looks at charter schools and media hype. (The Root)

Operating expenses: Alabama schools are borrowing from banks to fund basic school operations. (CNNMoney)

Race to the Top: Unsure whether to accept Race to the Top funds, a superintendent in Ohio asks what’s at stake. (The [Van Wert, Ohio] Times Bulletin)

School turnarounds: What happens to public schools that don’t meet federal testing requirements? (The [Salt Lake City] Deseret News)

New study urges caution in using “value-added” measures

The last five weeks have seen tremendous debate on the topic of teacher effectiveness, spurred in large part by recent events in the public-school systems of Washington, D.C. and Los Angeles.

Michelle Rhee, the D.C. Schools Chancellor, fired hundreds of teachers in July, and some of these educators were let go specifically because they were deemed ineffective. On the West Coast, meanwhile, the Los Angeles Times unleashed a firestorm this month with its series entitled “Grading the Teachers,” one part of which is an attempt to assign every elementary teacher (grades 3-5) in Los Angeles Unified School District a “value-added” score. (Note: A grant from The Hechinger Report helped fund the Times analysis, although we didn’t participate in the analysis.)

The Times explained “value-added” in the following way: “a statistical approach … [that] rates teachers based on their students’ progress on standardized tests from year to year. Each student’s performance is compared with his or her own in past years, which largely controls for outside influences often blamed for academic failure: poverty, prior learning and other factors.”

A new briefing paper, released yesterday by the Economic Policy Institute, calls into question “value-added” measures of teacher effectiveness. Its title, “Problems With the Use of Student Test Scores to Evaluate Teachers,” captures well the skepticism of its distinguished co-authors, who include Linda Darling-Hammond, Helen Ladd, Diane Ravitch, Richard Rothstein and Lorrie Shepard — all major players in the worlds of academia and education policy.

A central question in this debate has been, “Can we currently measure teacher effectiveness in fair, reliable ways?”

No one seems to have wondered whether we do measure teacher effectiveness in fair, reliable ways in the current system; there appears to be universal agreement the answer is “no.”

But can we? Or could we? And, if so, what would such a system look like? How big a role would, and should, value-added models play? These are questions that keep statisticians, psychometricians, economists and others awake late at night. These are questions that matter because the answers to them have the potential to affect, for ill or good, every student and teacher in the country.

But a question of equal or greater importance — and one that’s less frequently asked — is, “What does it mean for a teacher to be effective?”

Colorado took up this critical question in January, when Gov. Bill Ritter created the “Governor’s Council for Educator Effectiveness,” tasking the council with defining teacher and principal “effectiveness” by the end of 2010.

Defining, and then measuring, teacher and principal “effectiveness” is no small task. That’s one reason Ritter gave his council twelve months to do its work.

Educator “effectivness” is hugely important, which is something we learned the hard way from the No Child Left Behind Act. NCLB was a disaster in part because it fixated on teacher “quality” rather than teacher “effectiveness,” which meant the focus was on teacher inputs (degrees, certification) rather than student outputs (learning).

The discussion now seems to be firmly — and rightly — about outputs, not inputs. But which outputs matter? And how can we measure them in fair, reliable ways?

A widely shared view among educators is that a great many outputs matter. And some of the most vital outputs aren’t easily measured. Did a student come to love learning in a certain teacher’s class? Was a student motivated or inspired in important but intangible ways? Did a student gain much-needed self-confidence? Did he or she learn valuable lessons about working collaboratively, or sharing, or having empathy, or putting others before him- or herself?

What we can easily measure is how students perform on standardized tests in English and math. But what do these tests say about how much a student has actually learned? And how much of a student’s performance on such standardized tests is attributable to his or her English or math teacher? How can we fairly and reliably divvy up responsibility for what a student does or doesn’t learn? Presumably, learning is a joint venture — especially as children get older — and responsibility for learning must be shared among the student him- or herself, the student’s parents, the student’s teachers, the student’s administrators and perhaps even the student’s community.

As with so much of what matters most in life, we’re left with more questions than answers. But asking the right questions is essential. Answers don’t matter if we’re fixating on the wrong questions.

Asking how we could or should best define “teacher effectiveness” is of paramount importance. I have yet to see a good, comprehensive definition, but I’ve seen many less-than-good, incomplete definitions.

(Note: This post has been edited since it was first published on August 30, 2010.)

Recess round-up: August 30, 2010

A daily dose of education news around the nation – just in time for a little mid-day break!

Big business: of education. Washington Post Co. Chairman Donald Graham recently lobbied for his company’s subsidiary Kaplan Inc., as for-profit colleges face scrutiny from the federal government about deceptive loan practices in recruiting prospective students. (The Wall Street Journal)

Charter schools: “New Orleans has become a laboratory for education reform since [H]urricane Katrina. Charter schools, which are free to experiment, make up the majority of the city’s schools.” (Christian Science Monitor)

Early education: What can the rest of the country learn from a new report, “Lessons in Early Learning: Building an Integrated Pre-K-12 System in Montgomery County Public Schools”? The report, released today, provides an overview of how Montgomery County Public Schools “used local and federal dollars to craft, implement and improve a system-wide education reform” based on high-quality pre-kindergarten. (Pre-K Now)

Education reform: “It’s clear that teachers are frustrated,” said Christiane Amanpour in a report on the “education crisis.” She spoke with Secretary of Education Arne Duncan, American Federation of Teachers President Randi Weingarten and D.C. Schools Chancellor Michelle A. Rhee. (ABC News)

Governance: In a race for Superintendent of Schools in the state of Idaho, the incumbent is a businessman, the challenger is an educator. Who’s the best man for the job? (The [Spokane] Spokesman-Review)

International education: Ivy-educated Georgian President Mikheil Saakashvili told teachers state funding will be directed towards mathematics, physics, engineering, IT technologies and architecture. Chinese- and English-language learning are also encouraged. (Civil.Ge)

Evaluating teachers: A new brief from the Economic Policy Institute describes some of the problems with using student test scores to measure teacher effectiveness. (The Washington Post‘s “Answer Sheet”)

And on Sunday, the Los Angeles Times ran the third major story, called “No gold stars for successful L.A. teachers,” in its series on measuring teacher effectiveness with “value-added” modeling. Note: A grant from The Hechinger Report helped fund the work, though the Hechinger Institute did not participate in the analysis.

Racially homogeneous charters = freely chosen segregation?

In an op-ed in New York’s Daily News this week, Stuart Buck defends all-minority charter schools against accusations that they’re reviving racial segregation, arguing that “there is a type of freely chosen segregation that may further the goal of educational achievement.”

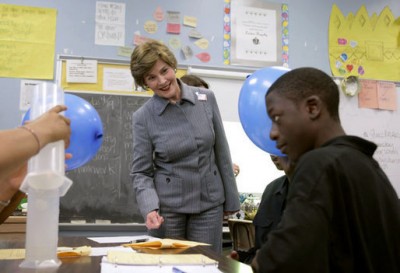

Former First Lady Laura Bush at a charter school in New Orleans (photo courtesy of Shealah Craighead)

Buck makes some interesting points, but readers need additional context to weigh the merits of his argument.

Elsewhere, including in The Washington Post, Buck has written about the phenomenon of “acting white.” Buck, a Harvard-trained lawyer who is now working on a doctorate in education, says black students can be discouraged from achieving when they’re placed in desegregated environments.

Here again, he makes the point that the hostility that blacks encountered during desegregation was counterproductive, hurting their “morale” and therefore their achievement.

Buck’s argument rings true for many blacks; I’ve spent the past year researching a case in the South in which black parents fought desegregation in order to preserve a traditionally black school and its strong culture of providing role models for black students and nurturing their achievement. For some excellent insights into the positive aspects of black schools under segregation, I recommend the work of Vanessa Siddle Walker of Emory University. She has examined how black schools cared about black students and their performance, something that evaporated when many black schools were closed and thousands of black teachers and principals lost their jobs in the aftermath of desegregation.

However, there is also a body of research out there suggesting that black self-esteem isn’t actually linked to achievement — so, although it might be common sense to think that higher morale would help black students do better in school, that’s not necessarily the case. This is not to say that it’s okay for schools to undermine how black students feel about themselves, just that it shouldn’t necessarily be the focus of efforts to close the achievement gap.

At the same time, other research has found that desegregation had a positive effect on closing the achievement gap for blacks, although for some caveats, see a new study by the Educational Testing Service in Princeton, N.J.

I also wonder if black parents (and charter school leaders, for that matter) would characterize their decision to enroll their child in a charter school that is racially homogeneous as “freely chosen segregation.” I’ve spent the past few weeks talking with parents and students at charters in New York City for a separate story. The parents live in racially homogeneous neighborhoods like Harlem and Crown Heights where the only other choices are racially homogeneous – and low-performing – public schools. When these parents seek out better schools for their children, the options don’t include high-performing, majority-white schools like P.S. 321 in Park Slope. The only choices that tend to be open to them are racially homogeneous charters.

Recess round-up: August 27, 2010

A daily dose of education news around the nation – just in time for a little mid-day break!

Race to the Top: New Jersey Education Commissioner Bret Schundler is out of a job now that the state lost the second round. The firing was “inevitable.” (The [Newark, N.J.] Star-Ledger)

New Orleans: Post-Katrina, nearly three-quarters of New Orleans’ public schools are charters. What can we learn? (Newsweek and The [New Orleans] Times-Picayune)

Also, the federal government announced this week that it “will give New Orleans $1.8 billion in a lump-sum reimbursement for schools that were damaged or destroyed in the flooding after Hurricane Katrina.” (New York Times)

Early ed: “Title I can … expand access to those children who are just above the income cutoff, to give them access to Head Start’s services.”And in San Diego, Emily Alpert writes that preschool is “a luxury for those who are rich enough to easily afford it, charity for those who are poor enough to deserve it, and a headache for those stuck in between.” (The Washington Post and Voice of San Diego)

Higher ed: West Virginia approves $8 million a year for two years to fund scholarships for college students. (Bloomberg Businessweek)

Special ed: Nikki Dowling writes that special-education needs are going unmet in New York City schools. (The Riverdale Press)

Stakeholders: Parents write a letter to President Obama, asking to be part of the administration’s school improvement efforts. Elsewhere, unions call for a “National day of action to defend public education” on October 7th. (The Washington Post and Defend Public Education)

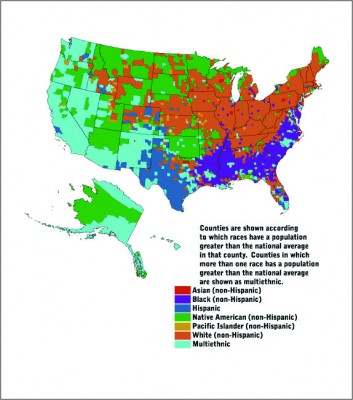

White voters vs. minority schoolchildren

White voters don’t like paying for the education of minority schoolchildren, or so we learn from a New York Times article this week that looked at places in New York where school budgets were voted down this year. The article’s author, Sam Roberts, found that in places where the majority of voters were white and the majority of schoolchildren were minorities, the budgets “fare[d] worse.”

Roberts also cites research that has shown the same trend to be true at the state level – in states where most voters are white but most children are minorities, spending on education is lower.

In part, this may be an older people vs. younger people dilemma. Many of these places are sites of changing demographics, where young minority families are moving in alongside a population of white empty-nesters who’ve stuck around after young white families have moved on. The white voters may be reluctant to pay for schools when they don’t perceive any benefits accruing to themselves or their children. In terms of property values, some might argue that the voters’ behavior is shortsighted because real-estate prices are so often dominated by school quality, especially in the suburbs where these trends are playing out.

Some political scientists have done research on a supposed “gray peril,” which is the idea that the elderly can act as obstacles in districts heavily dependent on local sources for school funds. But Michael Berkman and Eric Plutzer, in a 2005 book entitled Ten Thousand Democracies: Politics And Public Opinion In America’s School Districts, conclude that the gray peril is “grossly overstated.” They differentiate between the “migrant” and the “long-standing” elderly, a distinction that helps them build their case that the elderly who have lived in a community for a long time feel greater “loyalty” and thus support the local public schools (through higher property taxes) more than seniors who’ve only recently arrived.

On a larger scale, and in the longer term, it’s also interesting to think about how this phenomenon could play out at the national level. The U.S. is on track to have a population that is “majority minority,” and by the year 2025 nearly a third of all children in the country will be Latino.

Already, there is a reluctance to spend more on schools, particularly because of the recession. No Child Left Behind was often decried as an “unfunded mandate,” and now, with states in fiscal crisis, education has seen major cuts. The Obama administration is about to funnel several billion dollars into schools to lessen the impact of such cuts, but — excluding Race to the Top and, perhaps, money for charter schools — there’s been a lot of outcry against President Obama’s spending measures.

Yet, at the same time, a majority of Americans say the level of school funding makes a difference in quality, and a third say it’s a problem for their districts (up from a fifth in 2005), according to a survey published this week by Phi Delta Kappan and Gallup. We’ll have to wait and see whether these concerns translate into votes as demographics continue to shift in coming years.

Justin Snider contributed to this post.