White voters don’t like paying for the education of minority schoolchildren, or so we learn from a New York Times article this week that looked at places in New York where school budgets were voted down this year. The article’s author, Sam Roberts, found that in places where the majority of voters were white and the majority of schoolchildren were minorities, the budgets “fare[d] worse.”

Roberts also cites research that has shown the same trend to be true at the state level – in states where most voters are white but most children are minorities, spending on education is lower.

In part, this may be an older people vs. younger people dilemma. Many of these places are sites of changing demographics, where young minority families are moving in alongside a population of white empty-nesters who’ve stuck around after young white families have moved on. The white voters may be reluctant to pay for schools when they don’t perceive any benefits accruing to themselves or their children. In terms of property values, some might argue that the voters’ behavior is shortsighted because real-estate prices are so often dominated by school quality, especially in the suburbs where these trends are playing out.

Some political scientists have done research on a supposed “gray peril,” which is the idea that the elderly can act as obstacles in districts heavily dependent on local sources for school funds. But Michael Berkman and Eric Plutzer, in a 2005 book entitled Ten Thousand Democracies: Politics And Public Opinion In America’s School Districts, conclude that the gray peril is “grossly overstated.” They differentiate between the “migrant” and the “long-standing” elderly, a distinction that helps them build their case that the elderly who have lived in a community for a long time feel greater “loyalty” and thus support the local public schools (through higher property taxes) more than seniors who’ve only recently arrived.

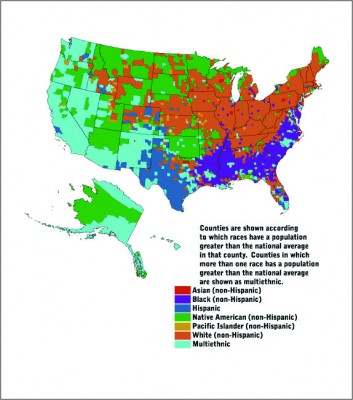

On a larger scale, and in the longer term, it’s also interesting to think about how this phenomenon could play out at the national level. The U.S. is on track to have a population that is “majority minority,” and by the year 2025 nearly a third of all children in the country will be Latino.

Already, there is a reluctance to spend more on schools, particularly because of the recession. No Child Left Behind was often decried as an “unfunded mandate,” and now, with states in fiscal crisis, education has seen major cuts. The Obama administration is about to funnel several billion dollars into schools to lessen the impact of such cuts, but — excluding Race to the Top and, perhaps, money for charter schools — there’s been a lot of outcry against President Obama’s spending measures.

Yet, at the same time, a majority of Americans say the level of school funding makes a difference in quality, and a third say it’s a problem for their districts (up from a fifth in 2005), according to a survey published this week by Phi Delta Kappan and Gallup. We’ll have to wait and see whether these concerns translate into votes as demographics continue to shift in coming years.

Justin Snider contributed to this post.