What should a fifth-grade classroom of the future look like?

Why is it, Linda Perlstein wonders in Slate today, that most American classrooms still look so much like they did back in the days of “Little House on the Prairie”?

“Very little about the American classroom has changed since Laura Ingalls sat in one more than a century ago,” Perlstein writes. “In her school, children sat in a rectangular room at rows of desks, a teacher up front. At most American schools, they still do.”

Slate is aiming to change the old-fashioned notion of a classroom by inviting readers to submit their own ideas for a more modern classroom. The winning design may be built in a new charter school.

“We’re seeking to collect your best ideas for transforming the American school. We’re asking you to describe or even design the classroom for today, a fifth-grade classroom that takes advantage of all that we have learned since Laura Ingalls’ day about teaching, learning, and technology — and what you think we have yet to learn. We will publish all your ideas on Slate; your fellow readers will vote and comment on their favorites; expert judges will select the ideas they like best, and, in about a month, we will pick a winner,” the blog post notes.

So what should a modern fifth-grade classroom look like? It’ll be interesting to see what comes out of this experiment. If nothing else, Slate may discover that many classrooms have, in fact, changed. Some fifth-grade classes these days have students sitting around long — or even round — tables, while others are grouped together in small circles. And there are classrooms where students sit on the floor for much of the day as well. But there are plenty of the old-fashioned kind, too.

So what should a modern fifth-grade classroom look like? It’ll be interesting to see what comes out of this experiment. If nothing else, Slate may discover that many classrooms have, in fact, changed. Some fifth-grade classes these days have students sitting around long — or even round — tables, while others are grouped together in small circles. And there are classrooms where students sit on the floor for much of the day as well. But there are plenty of the old-fashioned kind, too.

Slate offers a photo gallery that provides insight into what students like — and dislike — about their classrooms.

We look forward to seeing some of the new designs, and especially to thinking about they’ll impact the heart of what should be going on in any classroom — teaching and learning.

Evaluating teachers: Looking to the future

How should we evaluate teachers? It’s a huge question right now. And it seems like everyone has an opinion. But the one thing many people seem to agree on is that our current evaluation systems are inadequate. What a better system might look like – well, that’s still up for discussion. With so many stakeholders, so many different policies in different districts and so many fundamental questions on what makes a good teacher — and how best to measure student growth — it’s a hard question to answer definitively.

Yesterday, The New Teacher Project (TNTP) released a new report, “Teacher Evaluation 2.0,” that suggests six “design standards” for districts to follow when creating new teacher-evaluation systems. Most are fairly clear-cut: “all teachers should be evaluated annually,” or “evaluations should employ four to five rating levels to describe differences in teacher effectiveness.”

These are not very contentious ideas, even if they’re a departure from the status quo. (Historically, many districts have evaluated teachers on a simple binary scale of “satisfactory” or “unsatisfactory,” and many have also evaluated teachers sporadically, or not at all, after they earn tenure.)

New evaluation systems will require discussion and agreement on the components of an individual teacher’s evaluation as well as how it will then be used. On the latter point, TNTP believes that teachers deemed ineffective, after a certain amount of time, should be fired and that teachers deemed highly effective should be rewarded.

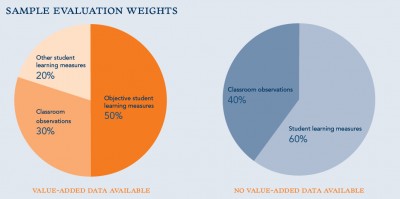

Sample Evaluation Weights (from "Teacher Evaluation 2.0," The New Teacher Project); click to enlarge

Perhaps most importantly, TNTP tries to tackle the former point as well. Many people argue that multiple measures should be used when looking at teacher performance, but far fewer explicitly define what those measures should be. The report suggests weighting what it calls “objective student learning measures” — TNTP’s example is value-added data — with classroom observations and “other student learning measures,” which might include “progress toward Individual Education Plan (IEP) goals, district-wide or teacher-generated assessments, and end-of-course tests.”

Although TNTP doesn’t provide fully fleshed-out descriptions of the “other student learning measures” it has in mind or fully specify everything an observation should include, these are still concrete possibilities for educators to explore. The report also lists handy pitfalls to avoid when designing new teacher-evaluation systems.

Deciding how to weight each component in a new teacher-evaluation system is what will likely prove most contentious. When value-added data are available, TNTP recommends that such data count as 50 percent of a teacher’s overall evaluation. While many applaud the use of value-added measures, several educators worry about their unreliability. Most recently, education historian and NYU professor Diane Ravitch has said that “value-added assessment should not be used at all. Never.”

The American Federation of Teachers (AFT), the nation’s second-largest teachers’ union, said in a press release that TNTP’s work is “is very much in line” with its own efforts on the teacher-evaluation front. But the AFT is worried about an overemphasis of student test scores in teacher evaluations: “[W]e are very concerned that the guidelines place too much emphasis on test scores, both as a proxy for student learning and as a measure of teacher practice. The AFT believes that basing 60 to 70 percent of a teacher’s rating solely on test scores puts too much weight on such data.”

To be fair to TNTP, it’s worth noting that “Teacher Evaluation 2.0” doesn’t quite suggest basing 60 to 70 percent of a teacher’s rating “solely on test scores,” as the AFT press release claims. Rather, TNTP’s recommendation is that 60 to 70 percent of a teacher’s evaluation be determined by a combination of “objective student learning measures” (largely test scores) and “other student learning measures” (which could potentially be things other than test scores, as explained above).

“Teacher Evaluation 2.0” builds on an important, much-discussed TNTP report, released last year, called “The Widget Effect: Our National Failure to Acknowledge and Act on Differences in Teacher Effectiveness.” Both reports are likely to be on policymakers’ and reformers’ minds as they set about designing — and then implementing — new teacher-evaluation systems. And as the authors of the latest TNTP report remind readers, “The success of any evaluation system — no matter how solid its design — ultimately depends on how well it is implemented.”

Justin Snider contributed to this article.

What (the best) teachers think

Last week, 50 “highly effective” teachers — as defined by a number of measures, including value-added test scores in some cases — descended on New York City to show off their skills to tourists and other passersby in Rockefeller Center.* NBC flew them in as a part of its Education Nation series, and along with stints of teaching in public, they met with various movers and shakers in the education world, including Education Secretary Arne Duncan and Teach For America founder Wendy Kopp.

All of the teachers are back in their classrooms now, but it looks like we’ll hear from them again in the near future. Jon Schnur, CEO and co-founder of New Leaders for New Schools, was behind the plan to bring the teachers to Education Nation and says it was originally conceived of as a one-time thing. The teachers, however, were thrilled to be asked their opinions about the important policy questions of the day, and liked the idea of becoming a more formal group.

Now, Schnur says, he’s working on getting them together again this winter. “A lot of them said they’d never had such an opportunity to engage in macro-policy,” he says. “They had a lot of energy to figure out how to build on this, and find more ways to be involved and share practices.”

The teachers were picked using a variety of methods, from word-of-mouth to value-added test scores. They also come from across the ideological spectrum – some are active in their unions, while others were quite critical of unions during the Education Nation events.

Schnur sees the potential for these teachers to help connect macro-policy to educational practices happening on the ground in classrooms, and the other way around: “Too often policymakers and classroom educators work in silos. People are making policy in a way that is not grounded directly in what’s been learned out of the most effective classrooms.”

Some might wonder if that isn’t the role teachers’ unions play, or should play. Schnur says his group of teachers can act as a “supplement to a lot of other bridges that are already out there.” He added: “We’re looking to have rich dialogue among teachers. We’re not looking to speak with one voice.”

(*Disclosure: Among the teachers invited to participate in Education Nation is my sister-in-law.)

Out of the starting blocks

By the time nine states and the District of Columbia were awarded more than $3.3 billion for school reform in the U.S. Department of Education’s “Race to the Top” competition in August, Delaware and Tennessee had already been hard at work for six months. What early lessons did leaders in those two states learn that might make it easier for states that won in the second round?

Read the case study for yourself

Answering that question was the goal of a new case study written for the Hechinger Institute on Education and the Media by June Kronholz, a longtime reporter and editor formerly with the Wall Street Journal. As former Tennessee Sen. Bill Frist, who is deeply involved in his state’s RttT plan, told Kronholz: “Nobody wants to go through the learning curve twice.”

For the case study, titled “Out of the Starting Blocks: Delaware and Tennessee Begin Their Race to the Top,” Kronholz interviewed the governors and education secretaries of both states, as well as political, business, union and community leaders; superintendents; school-board members; and education consultants. Their observations—what they said were their states’ successes and challenges in getting RttT off the ground—were remarkably similar, whether the speaker was the education advisor to the governor or the teachers-union chief.

That suggests second-round winners may face the same concerns, however dissimilar they are in size, demographics or political leadership. Here’s Kronholz on five areas that these states should attend to:

Communications: Teachers, parents, school-board members, legislators, and business and community leaders, among other interest groups, need to understand RttT before they can be expected to support it. But RttT is policy-heavy, with no easy storyline. To reach each of these key audiences, states must craft distinct messages. But most state education departments lack the expertise and manpower to mount a complicated public-information campaign.

Capacity: RttT commits states to huge and technically challenging initiatives, but state education departments, school districts and unions don’t have the expertise or staff to meet RttT’s requirements or its tight timelines. Some of the work—especially around teacher evaluations—is new, with few successful models for states to study. Both Delaware and Tennessee turned to private companies, consultants and nonprofit organizations for help. Second-round winners will need to reach out to the same organizations, which may become overstretched in the process.

Organization: RttT involves new work that doesn’t fit easily into old state education-department structures, which are geared toward compliance rather than innovation. That means rethinking how state departments do their jobs and deciding how to manage both the day-to-day responsibilities for RttT programs and the long-term planning. Any reorganization can create morale problems and fan resistance among the very people charged with implementing RttT.

Scopes of Work: District-level reform plans are supposed to be written by superintendents, administrators and teachers, who must explain in their Scopes of Work how what they are planning to do will affect student outcomes and how they will measure their progress. But many local educators in Delaware and Tennessee said they lacked the expertise, the exposure to best practices and the time for such complicated plans. The districts are under pressure because RttT requires those Scopes of Work to be submitted to the federal government within 90 days after winning an award.

Sustainability: Public disenchantment, bureaucratic resistance and political turnover can stymie and potentially undo RttT reforms after initial excitement about the federal grant fades. Sustained reform requires that community groups hold a state’s feet to the education-reform fire. More importantly, it requires a change in culture: Just as people expect clean water and safe roads, they must come to expect good schools for their children.

Overhauling how we recruit, support, evaluate and reward teachers: Where to start?

The topic of teacher effectiveness has taken center stage in national conversations about education reform. Educators and policymakers clash on how to measure “effectiveness,” and School Improvement Grants and other federal dollars have been tied to the idea of firing poorly performing teachers and rewarding those who already do well.

But many have argued that we can’t be so narrow-minded when we look at a teacher’s effectiveness, saying we can’t just get rid of all the teachers we don’t like. (In the words of George Walker, president of the Washington Teachers’ Union, you can’t just fire your way to better schools.) Instead, as California’s 2009 Teacher of the Year argues, we need to work on making all teachers better. This viewpoint has been present in the debate, but it often seems as though the question of how to improve all teachers’ effectiveness is overshadowed by the constant back-and-forth about how best to measure effectiveness, and then what to do with those measurements.

It’s this middle perspective — looking at how to improve all teachers — that the Joyce Foundation addresses in its recently unveiled website, Teacher Quality: What You Need to Know. Complete with a guidebook, Improving Teacher Quality: Here’s How, the site isn’t just for teachers and administrators. It’s also aimed at parents, policymakers and community leaders, the foundation says. (Disclosure: The Hechinger Report counts the Joyce Foundation among its many funders.)

Looking at a range of research and strategies – and arguing that no single tactic will change everything – the new site argues that “we need to improve how we recruit, support, evaluate and reward teachers to get the best teaching for kids who need it most.”

Federal court rules that teachers-in-training don’t count as ‘highly qualified’

After three years of court dates, appeals and petitions, Public Advocates, a nonprofit group based in San Francisco, scored a major victory yesterday when the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that teachers-in-training cannot legally be considered “highly qualified.”

After three years of court dates, appeals and petitions, Public Advocates, a nonprofit group based in San Francisco, scored a major victory yesterday when the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that teachers-in-training cannot legally be considered “highly qualified.”

Under 2001’s No Child Left Behind Act, if a student does not have a “highly qualified teacher” in his or her classroom – that is, one with a college degree in the subject area taught, state certification and demonstrated competence in basic skills as well as the subject area to be taught – parents must be notified. Teachers who aren’t highly qualified must all be spread throughout a school system, not concentrated in certain schools or types of schools (e.g., those serving disproportionately poor and minority students).

Yet ever since NCLB has been on the books, members of Teach for America and other alternative-certification programs have counted as “highly qualified” teachers, something the Public Advocates argued was a “major loophole” in the law. These teachers-in-training — to whom school districts have increasingly turned in hard-to-staff subjects like special education, math and science — receive a crash course during the summer and continue working toward certification while leading a classroom.

The federal court agreed with Public Advocates, overruling the verdict of a lower court, writing “The difference between having obtained something and merely making satisfactory progress toward that thing is patent.”

It’s hard to argue with the court’s reasoning. But what is perhaps less obvious is the more nuanced distinction that No Child Left Behind fails to fundamentally address. Having a highly qualified teacher doesn’t guarantee success in the classroom, and having a teacher who doesn’t meet the letter of the law hardly means that all students in that class are doomed to fail.

To put it simply, when it comes to quality control, outputs are a better measure than inputs. The national conversation is already moving away from a focus on what sort of preparation future teachers receive and looking more at how best to measure teacher effectiveness, and No Child Left Behind has been roundly criticized for the premium it places on highly qualified — rather than highly effective — teachers.

That’s not to say that concerns about the quality of alternative-certification programs are unfounded, or that parents shouldn’t be aware of the status (highly qualified or not) of their child’s teacher. After all, research on how teachers prepared in alternative-certification programs actually perform once they’re in the classroom — particularly in their first few years on the job — is mixed.

But a distinction that has dominated past conversations — who’s “prepared” and who’s “unprepared” — is slowly shifting to a discussion of who’s effective and who’s ineffective, regardless of a given teacher’s route to the classroom.

In other words, although the court’s ruling will have an impact, it might fall short of being a landmark decision, as we continue to move away from the idea of “highly qualified teachers” altogether. The upcoming reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, of which NCLB is simply the latest iteration, will almost certainly focus on educator effectiveness (outputs) rather than qualifications (inputs).

In the South, new push is on for more college grads

President Barack Obama has led the push for more U.S. college graduates, even though in a tough economy with competing demands the money to support the push hasn’t materialized — at least, not as Obama had once hoped.

From the South comes another new graduation initiative — this one calling for 60 percent of adults aged 25-64 in 16 southern states to earn a college degree or technical certificate by the year 2025. Lumina Foundation for Education issued a similar call — Goal 2025 — earlier this year, though it’s for the country as a whole instead of just a particular region. (Disclosure: Lumina Foundation is one of The Hechinger Report’s many funders.)

The latest graduation initiative comes at a time when talk of America’s slipping status in education is dominating conversation, highlighted most recently by Waiting for “Superman” and the NBC Education Summit. It also follows Georgetown University Researcher Anthony Carnevale’s estimate that states will need to increase the number of college degrees and certificates that are awarded by three percent to meet the nation’s future workforce demands.

The graduation initiative was announced in a report, “No Time to Waste” from the Southern Regional Education Board (SREB), that pushes new and specific goals for awarding different types of degrees and for raising college-graduation rates. The report also calls for paying closer attention to college costs and for improving the readiness of high-school students for college, long an obstacle to degree attainment. But it warns against tightening admissions standards as a way to improve graduation rates, saying that maintaining access must remain a priority for institutions of higher learning.

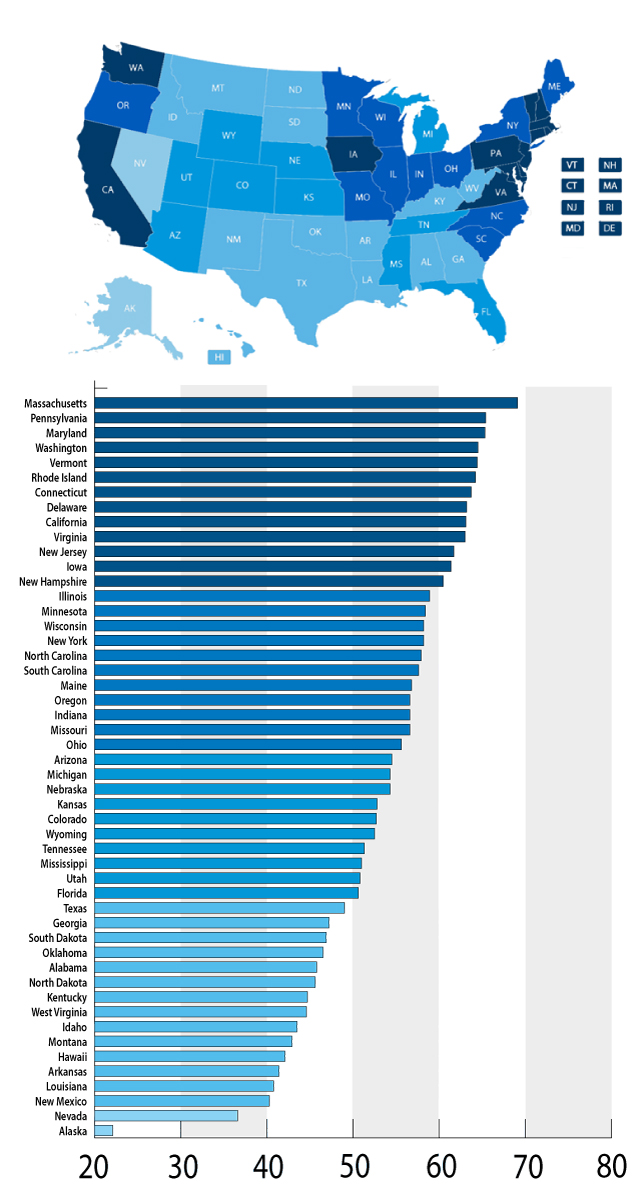

Southern states in particular are struggling to get more students through college, according to the report. The percentage of adults aged 25-64 who have two-year or four-year degrees in southern states ranges from a low of 26 percent to a high of 44 percent.

“We have no choice but to raise the education levels of the population substantially in the next 15 years if we want to remain economically competitive and continue to make social progress in our region,” said Dave Spence, the president of SREB.

What do college-completion rates look like in the South and elsewhere? Here are the six-year graduation rates for students in bachelor-degree programs in all 50 states. (Source: National Center for Education Statistics, IPEDS Graduation Rate survey)

The education reform show – now playing 24/7

Yesterday, NBC gathered a group of more than 300 teachers from around the country in a tent built on the skating rink at New York City’s Rockefeller Center — along with thousands who logged on online — and asked them provocative questions about charter schools, merit pay, teacher tenure and, of course, Waiting for “Superman.”

The Teacher Town Hall, as it was called, was part of the network’s “Education Nation” program, a weeklong event of blanket education coverage on NBC news-shows that coincides with a moment when suddenly everyone seems to be talking about education reform.

Teachers and how to make them better are huge topics in ed-reform discussions, but it’s pretty rare for the back-and-forth to involve teachers themselves, much less to give them time to make their case on national television.

Randi Weingarten, president of the American Federation of Teachers, attended the town hall and was impressed. “This is the first time I can remember that any conversation on school reform actually asked teachers what they think,” she said, adding that this forum was different than the usual scenario of having a union representative on a panel to defend teacher tenure.

That said, this was still TV, and the town hall was as concerned with entertaining the audience at home as it was with nurturing a substantive discussion. The show was competing in the same time slot as Sunday afternoon pro football, after all, and Brian Williams, the host, seemed intent on provoking a battle between the different “sides” of the ed-reform debates.

“Are teachers under attack?” was one of his first questions, followed by questions about what to do with teachers who don’t belong in the field. Williams also made quite a few plugs for the controversial film Waiting for “Superman,” which casts teachers’ unions in a fairly ugly light. (Education Nation screened the film twice over the weekend, which is interesting considering that NBC has no financial stake in the documentary — it’s a product of Viacom; an organizer said the timing of the film’s release and Education Nation was sheer coincidence.)

The resulting “feud” wasn’t as violent as a football game, but it did get angry at times. One teacher who spoke in favor of charter schools, where tenure isn’t usually an option, was hissed at by the audience. Afterward, another teacher said the forum had a “Jerry Springer-esque” feel.

Nevertheless, even with Williams pleading that teachers waiting in line to speak “be brief,” some teachers succeeded in touching on more complex themes. Many stood up to say they didn’t mind accountability, but teachers from across the political spectrum asked for measures that made sense – that were “humane,” and “authentic,” and not just based on test scores.

A constant refrain was that policymakers are making decisions about how to reform the public-school system with very little understanding of what it’s like to be in a classroom or what successful teaching actually entails. “You need a lot of passion, but passion is not going to cut it,” one teacher said, adding that teachers need expertise in pedagogy and their content areas, as well as in how to manage a classroom. And to develop all of these components, teachers repeated over and over, they need more support.

A teacher from the Bronx said that since entering the classroom, his own perspective on teaching has changed dramatically. He entered the profession because he thought he could do better than the teachers he’d had in high school, he said. But once in the classroom, he said he never encountered the drones he expected. Part of the problem with improving the profession, he concluded, was that we don’t agree “about what being a good teacher is.”

The NBC gathering seems to have at least sparked a conversation that includes teachers in figuring out this question. On Tuesday, “good” teachers will be giving model lessons before the public in Rockefeller Center. We’ll be going to check that out and will also be discussing how NBC picked the 300 teacher-participants, so stay tuned.

The transformative power of failure?

Can failure transform us in important — and healthy — ways? Should we champion failure as much as we do success? Is failure really just success by another name?

And in education, should we learn not just to live with but to love leaders who fail?

Such questions were at the heart of a recent BAM! Radio Network conversation in which I participated. The title of the talk was “When Leaders Flunk: The Critical Role of Failure to Success in Education,” and joining me in the discussion were Megan McArdle (of The Atlantic) and Holly Elissa Bruno (our host).

Earlier this year, McArdle wrote a piece in Time magazine — in a section called “10 Ideas for the Next 10 Years” — about the upsides of failure. She argued that “failure is one of the most economically important tools we have. The goal shouldn’t be to eliminate failure; it should be to build a system resilient enough to withstand it. … Yet instead of celebrating all our successes in building systems that fail well, we’ve become wedded to the fantasy of a system that doesn’t fail at all.”

Michael Jordan (photo by Steve Lipofsky, Basketballphoto.com)

McArdle was looking specifically at failure in the business world here, but our radio conversation addressed failure more broadly. Bruno began the discussion by quoting Michael Jordan, quite possibly the greatest basketball player in NBA history, who has said: “I’ve missed more than 9,000 shots in my career. I’ve lost almost 300 games. Twenty-six times, I’ve been trusted to take the game winning shot and missed. I’ve failed over and over and over again in my life. And that is why I succeed.”

This is a vital message for everyone to hear, especially children — who are often crushed when they fall short, perhaps because so many young people in the U.S. grow up hearing nothing but how amazing and unique they are. (Psychology professor Jean Twenge wrote an entire book, called Generation Me: Why Today’s Young Americans Are More Confident, Assertive, Entitled–and More Miserable Than Ever Before, on the pitfalls of the self-esteem movement.)

In reality, each of us probably isn’t that amazing or unique, no matter what our parents might say. Neither is anyone perfect. Failure is everywhere. (I remember meeting failure firsthand in fifth grade when report cards were distributed. I went home and bragged to Mom that I’d gotten all As. Her lightning-quick response, having just glanced at my report card? “No, you didn’t. Look here: see, there’s an A-.” Ouch. That was the last time I ever bragged about grades.)

If failure is ubiquitous, the question becomes how can we deal with it in productive ways? And should we as a society make a conscious effort to reduce failure’s stigma? Might it sometimes make sense to promote, rather than to shun, failure?

These are tough questions without clear answers.

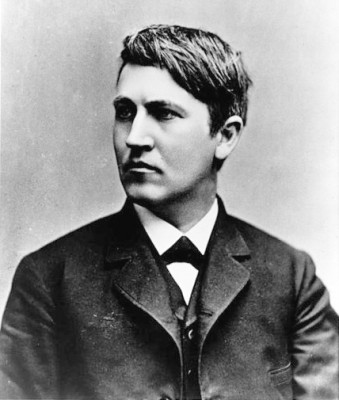

Thomas Edison, in 1878

McArdle pointed to the example of Thomas Edison, who needed nearly 10,000 tries to come up with a filament for the incandescent light bulb that would last more than a few hours. Some saw his thousands of attempts as wasted effort, but Edison saw them in a completely different light (pardon the pun!): he discovered 9,999 things that didn’t work as good filaments, which was useful knowledge in itself. By knowing what didn’t work, Edison was eventually able to find what did.

My favorite example of the relative definitions of failure and success comes from baseball. Ted Williams is the last major-league player to have hit over .400 in a single season, which he did in 1941. Nearly seven decades have come and gone but no one’s improved on his mark. That’s how hard it is to hit the ball. In fact, the very best major-league players typically “fail” at the plate twice as often as they succeed. But we’ve defined success in the major leagues as getting a hit roughly one out of every three at bats — which is very reassuring to me. Success, we must remember, is not a synonym for perfection.

On the subject of education, the question arose as to whether leaders should have the freedom to experiment and possibly fail. McArdle argued “yes,” and pointed out that we need to model failure for kids. They need to see adults learning to cope with uncertainty, risk and failure — and I couldn’t agree more.

But I’m somewhat wary of experimentation for experimentation’s sake, especially when those being experimented upon are real people — and, in the case of schools, children whose very lives can be dramatically affected (for better or worse) by our experiments. In this regard, I suggested we have an ethical obligation to be prudent — not too risky and not too reckless — in our educational experiments because they can have lifelong implications for students.

I also believe that failure at the individual level is a lot less harmful than failure at the institutional level – because a lot less is at stake. Leaders who fail don’t go down in flames alone; they typically take entire organizations with them.

Educational leaders should, of course, be willing to try new things and take the occasional, well-calculated risk. But they’d be wise to make decisions grounded in reliable research, not just based on passing fads. One reason urban school superintendents tend not to last very long in their jobs — the average tenure is about three years — is because they’re hired by people who want to seek quick and radical change, which usually means trying lots of new (and fairly risky) things. As Rick Hess has documented, the result is often akin to the spinning wheels of a vehicle stuck in mud: lots of (apparent) action that ultimately leads nowhere. That is, urban superintendents too frequently overpromise and under-deliver, in part because they’re almost required to overpromise in job interviews.

So, what’s your take on failure? Should we encourage more of it? Or should we, at the very least, seek to reduce the stigma associated with it?

Promise Neighborhood winners announced; disappointment for NJ

The U.S. Department of Education today launched a new anti-poverty program, Promise Neighborhoods, with the announcement of winners in a $10-million planning-grant competition. The program is intended to foster the creation of 21 versions of the Harlem Children’s Zone (HCZ) in cities, towns and Native-American reservations across the country. Winners will receive grants of up to $500,000 each to develop plans for new Promise Neighborhoods.

Among the winners is another program for Harlem, run by the Abyssinian Development Corporation. Although it is near the HCZ, Education Secretary Arne Duncan said in a conference call today that “it’s not the same community” as the one covered by the HCZ.

Other winners include Berea College in Kentucky, the Boys & Girls Club of the Northern Cheyenne Nation in Montana and Cesar Chavez Public Policy Charter High School in Washington, D.C.

By contrast, New Jersey, which launched its own state-funded version of Promise Neighborhoods last year, isn’t anywhere on the list. Two winning applicants from New Jersey’s own version, who also applied for federal money, are located in Newark and Camden, America’s poorest city. Both programs are receiving direct help from the HCZ to implement their plans. In fact, the Camden group, led by Rowan University, is at a training today in New York as they prepare to roll out their plans to improve schools and social services in a particularly poor area of Camden. A second application from Camden, led by Rutgers University, also lost.

Duncan said his department had received 100 grants that they wished they could fund. The deserving losers will be posted on the Education Department’s website, he said, in the hopes that private funders will take up their causes. “We’re hoping the private sector will come in and step up,” he said.

This is only the first round of the competition, so those who walked away empty-handed today could still win in the second round, which will provide money for program implementation rather than planning. The Department of Education has requested $200 million to fund these implementation grants, and officials say they anticipate funding 20 such grants. Winners and losers in the first round, as well as new entrants, are eligible to compete in the second round.

At the moment, however, it appears Congress might reduce the amount that the Obama administration has requested for the grants. Asked what will happen to the grant program if its appropriation is reduced, Duncan said, “If we only get $60 million, a lot of children will lose out.”