How should we evaluate teachers? It’s a huge question right now. And it seems like everyone has an opinion. But the one thing many people seem to agree on is that our current evaluation systems are inadequate. What a better system might look like – well, that’s still up for discussion. With so many stakeholders, so many different policies in different districts and so many fundamental questions on what makes a good teacher — and how best to measure student growth — it’s a hard question to answer definitively.

Yesterday, The New Teacher Project (TNTP) released a new report, “Teacher Evaluation 2.0,” that suggests six “design standards” for districts to follow when creating new teacher-evaluation systems. Most are fairly clear-cut: “all teachers should be evaluated annually,” or “evaluations should employ four to five rating levels to describe differences in teacher effectiveness.”

These are not very contentious ideas, even if they’re a departure from the status quo. (Historically, many districts have evaluated teachers on a simple binary scale of “satisfactory” or “unsatisfactory,” and many have also evaluated teachers sporadically, or not at all, after they earn tenure.)

New evaluation systems will require discussion and agreement on the components of an individual teacher’s evaluation as well as how it will then be used. On the latter point, TNTP believes that teachers deemed ineffective, after a certain amount of time, should be fired and that teachers deemed highly effective should be rewarded.

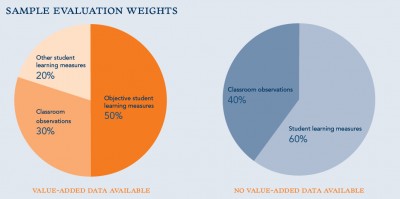

Sample Evaluation Weights (from "Teacher Evaluation 2.0," The New Teacher Project); click to enlarge

Perhaps most importantly, TNTP tries to tackle the former point as well. Many people argue that multiple measures should be used when looking at teacher performance, but far fewer explicitly define what those measures should be. The report suggests weighting what it calls “objective student learning measures” — TNTP’s example is value-added data — with classroom observations and “other student learning measures,” which might include “progress toward Individual Education Plan (IEP) goals, district-wide or teacher-generated assessments, and end-of-course tests.”

Although TNTP doesn’t provide fully fleshed-out descriptions of the “other student learning measures” it has in mind or fully specify everything an observation should include, these are still concrete possibilities for educators to explore. The report also lists handy pitfalls to avoid when designing new teacher-evaluation systems.

Deciding how to weight each component in a new teacher-evaluation system is what will likely prove most contentious. When value-added data are available, TNTP recommends that such data count as 50 percent of a teacher’s overall evaluation. While many applaud the use of value-added measures, several educators worry about their unreliability. Most recently, education historian and NYU professor Diane Ravitch has said that “value-added assessment should not be used at all. Never.”

The American Federation of Teachers (AFT), the nation’s second-largest teachers’ union, said in a press release that TNTP’s work is “is very much in line” with its own efforts on the teacher-evaluation front. But the AFT is worried about an overemphasis of student test scores in teacher evaluations: “[W]e are very concerned that the guidelines place too much emphasis on test scores, both as a proxy for student learning and as a measure of teacher practice. The AFT believes that basing 60 to 70 percent of a teacher’s rating solely on test scores puts too much weight on such data.”

To be fair to TNTP, it’s worth noting that “Teacher Evaluation 2.0” doesn’t quite suggest basing 60 to 70 percent of a teacher’s rating “solely on test scores,” as the AFT press release claims. Rather, TNTP’s recommendation is that 60 to 70 percent of a teacher’s evaluation be determined by a combination of “objective student learning measures” (largely test scores) and “other student learning measures” (which could potentially be things other than test scores, as explained above).

“Teacher Evaluation 2.0” builds on an important, much-discussed TNTP report, released last year, called “The Widget Effect: Our National Failure to Acknowledge and Act on Differences in Teacher Effectiveness.” Both reports are likely to be on policymakers’ and reformers’ minds as they set about designing — and then implementing — new teacher-evaluation systems. And as the authors of the latest TNTP report remind readers, “The success of any evaluation system — no matter how solid its design — ultimately depends on how well it is implemented.”

Justin Snider contributed to this article.