Rural schools remembered

The U.S. Department of Education — if it wins budgetary approval for a third round of Race to the Top — is proposing to do things a bit differently this time. Instead of states competing against one another, individual districts would compete for grants from a $900 million pot — and the Department of Education will set aside a certain (as yet unspecified) amount for rural districts.

“We want to make sure that if we play at the district level that we have a good representation of rural, urban and suburban districts,” Secretary of Education Arne Duncan said in a press call on Monday. “We want to make sure that rural districts that may not have a grant writer, may not have the resources of a large urban district, have an absolute chance to compete and to be successful.”

Rural schools serve nine million students in the U.S., or about 20 percent of the nation’s total. Although large urban districts are often highlighted as evidence of academic failure, rural areas have their fair share of problems as well. About a quarter of students in rural areas drop out, and roughly a third of the 5,000 or so schools eligible for federal School Improvement Grants were in rural areas.

The Department of Education was criticized when it handed out School Improvement Grants last year, as members of rural communities argued that the four models for fixing failing schools – turnaround, transformation, restart and closure – didn’t account for some of the specific challenges their areas face, such as difficulty recruiting staff. It’s hard to fire all, or even half, of a school’s teachers when there isn’t a ready supply of other teachers who could be hired.

In March 2010, 22 senators from largely rural states wrote to Duncan, asking that rural schools have an equal opportunity in 2011 to get the competitive grant money, and arguing that reforms such as distance-learning can play a uniquely important role in more remote areas of the country.

Earmarking money for rural districts in a possible third round of Race to the Top seems to be the Obama administration’s way of agreeing with them.

In tough times, even more reason to spend on innovation, Obama says

President Barack Obama -- with science teacher Susan Yoder and Education Secretary Arne Duncan in the background -- talks with eighth-grade science students at Parkville Middle School and Center of Technology in Baltimore, Feb. 14, 2011. (Official White House Photo by Pete Souza)

President Barack Obama unveiled plans for a significant increase in federal spending for public schools on Monday at a Baltimore middle school known for the kind of innovation he wants to see a lot more of — even if it requires spending scarce resources.

“We wanted to highlight the great work you’re doing in math and science and engineering,” Obama told students at Parkville Middle School and Center of Technology. “Your success ultimately is going to mean America’s success.”

With those words, the president made it clear that funding for math and science education will be a part of the $3.73 trillion budget for 2012 that he released on Monday, even as Republicans are demanding deeper cuts and as other areas of education will get less, not more. Obama asked for $77.4 billion in his education proposal, not including a boost in financial aid in the form of Pell grants. (Obama wants to maintain the maximum Pell grant at $5,550 per college student. House Republicans want to cut such grants by about $845, or 15 percent.)

The president’s emphasis on innovation comes at a time of serious concern about U.S. performance in math and science. A recent Hechinger Report look at science education found that “Eighth-graders’ scores on the on the 2007 Trends in International Math and Science Study (TIMSS) put the United States in the middle of the pack in science achievement, behind nine other countries, including Japan and Russia.”

Schools across the country are in trouble, as billions in emergency stimulus money from the federal government run out. Obama and U.S. Education Secretary Arne Duncan said on Monday they hope to protect the Race to the Top program — and even continue the competition. The budget includes some $900 million for the program, which includes competitive grants to school districts instead of states. There’s also some $600 million for school turnaround grants.

The budget also makes some far-reaching cuts, as Duncan pointed out during a conference call with reporters on Monday. “As the president said … to win the future, we need to invest in education … essentially we must cut where we can to invest where we must.”

He added that “these are some of the toughest budget times we’ve seen in decades.”

Education Week has some good coverage of the proposed budget. The Obama administration’s budget proposal for higher education is dissected here and here.

Teachers union embraces reforms following Milwaukee newspaper series

The Wisconsin teachers union said this week it is in favor of efforts to improve teacher quality and even would allow student data to be used in teacher evaluations.

The announcement comes on the heels of an eight-part series on teacher training and evaluations reported by the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel in collaboration with The Hechinger Report. The front-page stories, which ran in November and December 2010, took the state and union to task for not moving quickly enough on reforms.

The union outlined its vision for a new statewide teacher evaluation system on Tuesday.

The plan proposes to:

– Establish a system to ease underperforming teachers out of the profession

– Use “various student data to inform evaluation decisions and to develop corrective strategies for struggling teachers”

– Offer performance pay for teachers

– Break up the Milwaukee Public Schools into smaller, “more manageable” components (though the local teachers union in Milwaukee has not signed off on this, says the Journal Sentinel).

The union says it wants to work on legislation that would put these reforms into place by 2015.

L.A. Times series ‘Grading the teachers’ wins 2010 Philip Meyer Journalism Award

The Los Angeles Times took top honors today in the 2010 Philip Meyer Journalism Award competition for its “Grading the teachers” series last fall. The award, which comes with a check for $500, is given by the National Institute for Computer-Assisted Reporting (a joint program of Investigative Reporters and Editors and the Missouri School of Journalism) and the Knight Chair in Journalism at Arizona State University’s Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication.

A grant from The Hechinger Report helped fund the analysis — completed by senior economist Richard Buddin of RAND — on which the Times based its series. (The Report did not participate in the analysis.)

The Philip Meyer Award “recognizes the best uses of social science methods in journalism,” according to an announcement by Investigative Reporters and Editors, and it will be presented on February 25th at the 2011 Computer-Assisted Reporting Conference in Raleigh, N.C. Second place, for a 12-month investigation entitled “Sexual Assault on Campus,” went to a collaboration of seven news organizations led by The Center for Public Integrity. The Orange Country Register, in Southern California, won third prize for its four-part series “Immigration and California.”

In addition to Buddin of RAND, those cited for their work on the Los Angeles Times series include Jason Felch, Jason Song, Doug Smith, Sandra Poindexter, Ken Schwencke, Julie Marquis, Beth Shuster, Stephanie Ferrell and Thomas Lauder.

The Times series, which includes answers to frequently-asked questions about value-added analysis, also has been translated into Spanish.

Additionally, The Hechinger Report has created a “GO DEEP” page for readers interested in exploring the topic of teacher evaluations more broadly.

Here is the full award citation for the Times:

“‘Grading the Teachers’ is a first-rate example of strong watchdog story-telling combined with innovative use of social science methods. Indeed, the point of the project was the failure of Los Angeles school officials to use effective methods to measure the performance of classroom teachers. The Los Angeles Times, applying a method called gain-score analysis to a huge database of individual students’ test scores and their teachers, identified the most and least effective teachers based on how much the students’ scores improved. The Times hired a national expert in gain-score analysis to do the data crunching, adding credibility to the results, but also did additional statistical analysis to identify high- and low-performing schools and otherwise verify their findings. In identifying and rating 6,000 teachers by name, the Times outraged the teachers’ union, but the series has prompted district officials to begin negotiating with the union to use the gain-score method in evaluations. Another sign of the impact of this series is that newspapers across the country have begun requesting similar data from local school districts.”

More lessons from Indianapolis

Ten days ago, The Hechinger Report took a look at Indianapolis, asking if charter schools — either through competition or collaboration — could be a means of improving achievement across a failing school system, as policymakers have often argued.

Though charters themselves are doing well in the city, the public-school system is still struggling. Moreover, Indianapolis Public Schools (IPS) Superintendent Eugene White argues that competition from charters is hurting his city’s public-school system — and that most charters aren’t even innovative.

A recent report out of Vanderbilt University’s National Center on School Choice, also focused on Indiana, highlights the complex relationship between theory and practice in charter-school policy.

The report, “Taking Charge of Choice: How Charter School Policy Contexts Matter,” takes a look at how the state’s charter-school law came to be in 2001, detailing the problems facing the Indianapolis Public Schools at the time and how charter policy was crafted to help solve them.

The problems, as described in the report, were multiple: Indianapolis had one of the lowest graduation rates in the country, the city’s population was shrinking, and in a messy school system with 11 different districts, there was little or no direct accountability for school performance.

Charters emerged, promoted by Republican State Senator Lisa Lubbers and former-Indianapolis Mayor Bart Peterson, as a way to inject accountability and innovation into the state’s schools.

Peterson became the first mayor in the country with independent authority to grant charters. (To date, no other mayor has been given the same authorizing power over charters.) As Peterson put it in his 2001 State of the City address: “A sponsor must evaluate charter school proposals and hold the schools accountable for their performance … A mayor is accountable to the public for all decisions and the decisions I might make as a charter school sponsor would be no exception.”

Indeed, the mayor’s Office of Education Innovation still takes pride in how it holds charter schools and their authorizer accountable. From a rigorous application process — the mayor is allowed to authorize up to five new charters a year, though he has done so only once — and yearly reports (based on test scores and observations) to transparency about schools’ finances, the mayor’s office works to ensure it only opens, and keeps open, solid schools. It remains acutely aware that in any given election, the mayor’s fate may be tied directly to charter-school performance.

But while charters have brought some accountability to the district (at least for the schools the mayor has opened), the second policy goal — spurring innovation in all schools — remains mostly unmet.

The report’s author, Claire Smrekar, found that there have been many developments that “represent the potential for achieving some of the promises of charter school reform,” including the introduction of Teach For America and The New Teacher Project in Indianapolis, as well as new inter-institutional partnerships (such as that among IPS, the University of Indianapolis and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation).

Yet all of this potential has not been realized in the city at large, according to Smrekar: “To be sure, the academic trajectory for the more than 50,000 students enrolled in that system are [sic] far less than the goals established by the charter school policy network and policy entrepreneurs.”

Rote memorization: Overrated, or underrated?

Among the countless catchphrases that educators generally despise are “drill-‘n-kill” and “rote memorization.” In keeping with their meanings, both sound terrifically unpleasant. To learn something “by rote,” according to the Random House dictionary, is to learn it “from memory, without thought of the meaning; in a mechanical way.”

The fear is that we’re turning our children into automatons by force-feeding them useless bits of information — facts that can be found instantly on Wikipedia, like the dates of the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648) or the equation for calculating the area of a circle (πr2).

But is it possible that memorizing things is actually underrated in modern American society? Could one make a convincing case that it’s not just useful but vital for people of all ages to memorize things?

The answer to both of these questions, I believe, is yes. And a recent discussion on the BAM! Radio Network in which I participated focused on this very topic — the value of rote memorization. The conversation, hosted by Rae Pica, featured Daniel Willingham (a professor of psychology at the University of Virginia), Joan Almon (executive director of the Alliance for Childhood) and me.

Because “rote” learning and “memorization” have negative connotations for most people, it might be better to speak of learning things by heart. And, as Willingham points out in our discussion, learning things by heart is something children automatically do. That is, it comes naturally to them — whether it’s being able to recall all the words to a nursery rhyme or knowing the plot of a story (if not the story itself, word for word) before one is actually able to read. Willingham says that the key is engagement: “If you’re really engaged, memory comes pretty automatically.”

Learning things by heart can be useful for any number of reasons, some of which we discuss in the radio show. As an English teacher, I’ve often made my students memorize poetry — and just as often some have pushed back, accusing me of assigning meaningless “busy work.” I love that accusation because it provides me the perfect opportunity to explain why memorizing a poem is, in fact, a worthwhile activity.

In 10th grade, I learned by heart the prologue to the Canterbury Tales (in Middle English, of course), and to this day I can recite it and a lot of other Chaucer that I had to memorize as an undergraduate. I can also do Robert Frost, Heinrich Heine (in German) and Shakespeare (“To be or not to be”) at the drop of a hat. Also, should you wish to know, I could tell you the first 100 digits or so of π. Yeah, it’s kinda geeky — but it’s kinda cool, too.

And here’s a little-known secret: learning things by heart isn’t as hard as many people imagine. Most people, I think, could learn the first 100 digits of π in an hour. (No one believes me until they actually try.) The trick to remembering the digits long-term, however, is constant repetition — especially when you’re early in the process. I’m able not to forget Hamlet’s soliloquy because I learned it really well a decade ago — practicing multiple times a day for weeks on end — and because I now check myself every few weeks or so to see if I still know it.

For inspiration on the memorization front, check out the video below of a three-year-old reciting Billy Collins’ poem “Litany.” This serves as a lovely reminder of what the human brain is capable of. (Notice what the young child’s intonation on certain lines reveals: he hasn’t learned this poem “without thought of the meaning; in a mechanical way” — Random House’s definition of “rote” learning. He’s wiser and more aware of what he’s saying than many of us might initially think.)

Anyway, here are some of the reasons I give skeptical students for why learning things by heart is worthwhile:

First, it’s a challenge, and one in which those who succeed can take pride. (On this front, I’ve always been much more impressed by Broadway actors than their Hollywood counterparts because the former can’t screw up — they have to nail everything the first time — and because they don’t get cue cards off-camera to prompt them. Hollywood actors, by contrast, can get away with memorizing just a handful of lines and often re-shoot a single scene scores of times to get it right.)

Second, it’s good exercise for your brain. Many people these days seem to believe that our digital devices will remember everything for us — and they will, but they’re not much help when we can’t find them, or they’re broken, or they’ve been left at home. How will you call your best friend to reschedule that lunch appointment — you don’t even know her phone number! And she’s your best friend?

Third, and most importantly, new insights are gained in the process of memorization. You see things to which you were previously blind; you uncover a play on words, assonance, alliteration, analogies. It is for this reason, I believe, that the great Russian-American novelist Vladimir Nabokov declared that there’s actually no such thing as reading — there’s only re-reading. (“Curiously enough, one cannot read a book: one can only reread it. A good reader, a major reader, an active and creative reader is a rereader,” Nabokov wrote in his Lectures on Literature.)

The same holds for TV shows and movies: you see so much more on a second, third and fourth viewing. You don’t truly see anything the first time you watch it. And, in my experience, this applies no less to music: hearing something for the first time is more akin to hearing it not at all than to truly hearing it. The work is too new, too unknown, to us; we can’t make heads or tails of it because we suffer from sensory overload. Quite simply, there’s too much going on for us to get anything but a glimpse of the work’s essence.

It’s only with multiple readings, viewings and hearings, then, that we actually begin to understand, see and hear. We’re deaf and blind in our first encounters with things.

And this is why practice matters so much as well. It’s our chief hope for transcending mediocrity.

We say “practice makes perfect” in English but this, I think, is somewhat misleading because perfection is rarely attainable. There’s no such thing as a “perfect” performance of a Beethoven sonata. And while perfection in sports isn’t inconceivable — I suppose a tennis player could win a match in straight sets without dropping a single point, or a quarterback could complete every pass (with no interceptions) in a football game — it’s highly unlikely. Thus, I prefer the German version of the saying: “practice makes the master.” Those who are the best at things typically become so through nonstop practice. It’s not the only factor, of course — natural ability matters hugely, too — but it does seem to be a necessary ingredient. As Amy Chua, of “Tiger Mother” fame, says in her new book: “Tenacious practice, practice, practice is crucial for excellence; rote repetition is underrated in America.”

Why are rote repetition and memorization underrated in America? As I say on the radio show, they’ve gotten a bad rap in part because they lend themselves too well to standardized testing. It’s much easier — faster, cheaper — for me to determine whether you know when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor (December 7, 1941) than whether you can convincingly explain how and why the Treaty of Versailles set the stage for World War II. Yes, the curriculum has narrowed (even Arne Duncan admits it!), the “what-gets-tested-is-what-gets-taught” phenomenon is very much alive, and there’s a lack of critical-thinking skills among today’s young people.

These sad facts, however, are more the result of our over-reliance on multiple-choice tests than anything inherently evil about repetition or memorization.

Can standards for charter schools improve their performance?

A coalition of groups announced today the publication of new national standards for charter schools. Here’s the lead of the press release:

“A coalition of leaders in the national charter movement is today announcing the culmination of a four-year, federally-funded project titled Building Charter School Quality (BCSQ) that has resulted in the development of national standards on charter school quality, and nationwide progress based on those standards.”

Already, charters are supposed to live up to the same standards as traditional public schools, but be subject to more stringent accountability. That is, they live and die by state standardized test scores. (For an interesting look at charters that have shut down, check out this study by the pro-charter group, Center for Education Reform.)

Many charters, especially those in urban centers that require a lottery to get in, do phenomenally well. Nevertheless, national studies have shown that, overall, charter school performance isn’t any better than that of traditional public schools. One of those studies was conducted by CREDO at Stanford, which is a sponsor of the new charter standards.

The idea behind these standards is similar to the idea that drove the development of the Common Core State Standards: creating common standards will help schools and districts know what they should be working toward and will lift up all boats. The key is in implementation, however. Only time will tell if these standards make a difference in ensuring high quality across the board, where current accountability measures (which differ by state) apparently have not.

Memphis: A reminder that the fight over desegregation never ended

The city of Memphis, Tenn. and the suburban county that encompasses it are locked in a battle over whether to consolidate their schools into one large system. The city board, which proposed the merger, says the move is in reaction to a county proposal to transform itself into a “special district,” which would keep it from having to give some of its tax revenues to the city schools, as it does now. For Memphis, where the students are majority low-income and the tax base reflects this, the special district scenario could prove disastrous.

The fight is a flashback to the 1970s, when school districts across the country faced busing plans intended to undo decades of racial segregation. As the New York Times notes, Tennessee back then had to pass a law to keep suburban school districts from transforming themselves into special districts in an effort to avoid desegregation.

Louisville, Ky. is one of the bigger examples of this sort of merger from that era. The consolidation of the county and city there caused a decade-long conflict that still simmers. A large part of the conflict was busing: The merger came with a court order that the nearly all-white county schools had to send their students into the nearly all-black city schools, and vice versa. Many administrators and teachers lost their jobs, the power that black officials had held in the city system was diluted, and several formerly black schools were shuttered.

Although researchers, Louisville leaders, and the city’s school board have argued that, in the end, the merger and desegregation were a success — a qualified one, I would argue, as the city still has an achievement gap between white and black students, although the gap in Kentucky is much smaller than other states — and though it eventually was well-received by the public, the conflict reemerged with the Supreme Court case in 2007 that ended race-based school assignments.

Busing isn’t an issue in Memphis this spring, where voters will decide on the merger idea in March. But many of the deeper issues that fueled the battles of desegregation are still there, even if busing is off the table. How much do the suburbs and their more well-to-do residents owe to the central cities that anchor them and the more disadvantaged residents who live there? Can inner-city school systems be resurrected on their own, or does the concentration of poverty make that an impossible task?

One interesting piece of the Memphis story is that black leaders — including the head of Martin Luther King Jr.’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference, Rev. Dwight Montgomery — are not supporting the merger plan. “If the school systems are unified in a divided community, how does that help the children?” Montgomery has asked.

Right now, Memphis is undergoing a major overhaul of its schools thanks in part to the Race to the Top competition, which Tennessee won in the first round last year. The city has rolled out a major teacher effectiveness initiative, and a spokesperson pointed out to me the other day that the high school graduation rate there has increased in recent years. Can these efforts — which are at the cutting-edge of school reforms going on across the country to lift high-poverty, high-minority schools out of failure — close the achievement gap between those suburban white kids in Shelby County and those inner-city black kids in Memphis?

Many assume that the story of desegregation is long over — that the 2007 Supreme Court decision is an epilogue in a narrative about police dogs and black children and national guard members and Martin Luther King Jr. that elementary school children study during Black History Month. But the Memphis battle is a reminder that these issues still haunt us, and continue to defy any easy solution.

Obama pushes education investment in State of the Union speech; Calls Race to the Top ‘most meaningful reform’ in a generation

President Barack Obama hit the education theme hard in his second State of the Union address last night and set the stage for a fight with Congressional Republicans over federal education spending as he prepares to release his budget for this year.

Education was one of the “pillars” of change that he said needs an infusion of money, along with innovation and infrastructure, despite the tough economy right now. In particular, he narrowed in on science, technology, engineering and math, known as the STEM fields, calling for the preparation of 100,000 new STEM teachers in the next decade.

Obama also seemed geared up to fight for another round of funding for Race to the Top, which he called the “most meaningful reform of our public schools in a generation.” At the Washington Post, Nick Anderson notes that this is a “debatable” characterization of the competition. Here’s what Russ Whitehurst at Brookings had to say: “It is far too soon to tally the results in terms of student achievement, but there is no doubt that it was the largest expansion of federal executive branch control in any generation.”

The speech included some tough love for teachers. Obama referenced the debates over tenure and merit pay: “We want to reward good teachers and stop making excuses for bad ones.” But he also called on “every young person listening tonight” to become a teacher “if you want to make a difference in the life of our nation.”

The president couched his argument in favor of greater investment in education by comparing the U.S. school system unfavorably to those of India and China, where students in Shanghai just trounced their international peers on the PISA test. The New York Times notes, however, that Obama may have overstated his case: “The president’s remarks suggested that the United States puts less of a priority on schooling. But that does not appear to be accurate at least in terms of compulsory education. China requires nine years of education and India just eight.”

Those countries are investing in improving their educational systems, however (see here and here), while across the U.S., state education budgets are being slashed in response to the fiscal crisis. Still, although some have suggested that education could be an area where Obama could find room for negotiations with Republicans — specifically, through the reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) — others are skeptical. Despite the bipartisan seating arrangements last night, the newest members of the House have not seemed eager to embrace very many of Obama’s investment ideas, education included.

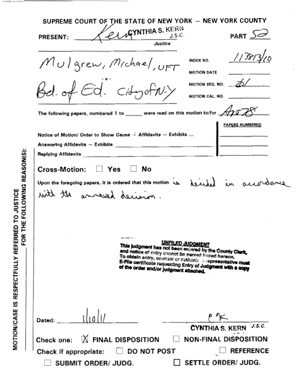

A closer look at Justice Kern’s ruling in NYC value-added case

On Monday, January 10th, Justice Cynthia Kern ruled that the decision by the NYC Department of Education to publicly release Teacher Data Reports (TDRs) with individual teachers’ names attached was not “arbitrary and capricious.” That the chips fell this way isn’t terribly surprising.

Kern’s ruling is interesting more for what it doesn’t say than for what it does. And the United Federation of Teachers (UFT) has already appealed, so her ruling almost certainly won’t be the final word on this subject. As I wrote last month, “regardless of what Judge Cynthia Kern decides, it’s safe to say that the current teacher-evaluation system is broken in most school districts nationwide — and that value-added analysis is here to stay.”

Among the highlights of what Kern did say:

• “This court is not passing judgment on the wisdom of the decision of the DOE, whether from a policy perspective or from any perspective, or whether the DOE had discretion under the law to make a different decision, nor is this court making any determination as to the value, accuracy or reliability of the TDRs.”

• “The UFT’s argument that the data reflected in the TDRs should not be released because the TDRs are so flawed and unreliable as to be subjective is without merit. The Court of Appeals has clearly held that there is no requirement that data be reliable for it to be disclosed. … Therefore, the unredacted TDRs may be released regardless of whether and to what extent they may be unreliable or otherwise flawed.”

• “Finally, the UFT’s argument that the DOE assured teachers that the TDRs were confidential means that they cannot be disclosed under FOIL is without merit. … regardless of whether Mr. Cerf’s letter constituted a binding agreement, ‘as a matter of public policy, the Board of Education cannot bargain away the public’s right to access to public records.’ … Accordingly, the DOE’s assurances that the TDRs would remain confidential cannot shield them from disclosure.”

What Kern didn’t say is that the court is essentially providing political cover for the NYC Department of Education to make a controversial decision — the final result of which is that, to many observes at least, the court will end up looking like the bad guy instead of the DOE.

But Kern’s ruling isn’t an endorsement of the DOE’s decision, as she makes clear in the first excerpt above: “This court is not passing judgment on the wisdom of the decision of the DOE.” The DOE could have decided otherwise — not to release the TDRs with teachers’ names attached — and then a very different lawsuit likely would have followed: media outlets, rather than the union, would probably have been the plaintiffs taking the DOE to court.

That lawsuit, however, never happened because the DOE decided — without being ordered to do so by any court — that it had no choice but to comply with the Freedom of Information Law request filed by various media organizations. Joel Klein explained the DOE’s rationale in a letter to city principals last October: “As it is the City’s legal interpretation that we are legally obligated to provide the media this information, it is our intent to provide the data as requested.” But it’s important to be clear here that this was an internal decision made by the DOE, not an action taken in response to a court order.

It’s also worth recalling Cathie Black’s position on whether the TDRs should be released with teachers’ names attached, which she articulated to the editorial board of the New York Daily News in December: “If it has to be released [under the law], we’re going to have to release it. … [but] Unless we are forced to do it now, we would not be releasing the data. We won’t be releasing the data.” Daily News reporter Joshua Greenman charitably characterized Black’s position on the to-release-or-not-to-release question “not black and white.”

All of this to say that the DOE has repeatedly maintained its actions are required by law, even though no court has issued an order to that effect. Whether a court would rule that the TDRs (with teachers’ names attached) must be publicly released remains in doubt; it’s a question that Justice Kern wasn’t considering, as she says in her decision.

For perspective on this case, I spoke with Professor Michael Rebell of Teachers College and Columbia Law School. Rebell — who was co-counsel for the plaintiffs in Campaign for Fiscal Equity vs. the State of New York (2003), a case that resulted in a planned $5.6-billion infusion of funds into NYC schools — told me that “the court’s ruling was outrageous. … One could certainly argue that this [ruling itself] was arbitrary and capricious.”

Rebell clarified that the “arbitrary and capricious” standard on which Kern was deciding the case gives a lot of discretion to judges. “A different judge might have ruled a different way, and an appeals court might rule another way,” Rebell said. If he were the judge, Rebell told me, he “would have gone the other way.”

Rebell explained his thinking this way: “The underlying facts are … that value-added has a lot of promise as an approach, but at this point it is not perfected enough that you can fairly identify teachers and say that this teacher is good or that teacher isn’t.”

What’s next? The UFT has appealed Kern’s decision, and the DOE has agreed to await the outcome of the appeal before taking any action. This means, Rebell pointed out, that it’s actually in the union’s interest for the appeal to take a long time because there’s no fear of teachers’ individual TDRs being released in the interim — that is, if the DOE sticks to its word.