American Graduation Initiative gets new resources

President Barack Obama’s American Graduation Initiative (AGI) took a step forward today with the announcement of a “college completion tool kit” — as well as a new grant competition — by Vice President Joe Biden.

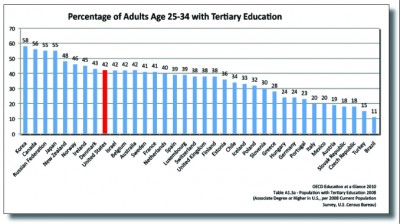

Although first announced in July 2009, the AGI has seen little action on the federal stage aside from more money going toward student financial aid. Community colleges lost out on $12 billion over 10 years last March that would have been a cornerstone of the initiative, which calls for the U.S. to have the highest percentage of college-educated adults in the world by 2020.

The U.S. Department of Education has now divvied up the number of graduates each state will need to produce to pull its weight in achieving this goal. The Department is also promising to provide states with technical assistance and “target available resources to assist states in their college completion efforts, and report by January 1, 2012, where states stand in terms of college and completion goals, numeric objectives, plans, and early achievements,” according to the tool kit.

Some of the strategies advocated in the tool kit should cost little or nothing — such as targeting adults, making it easier for students to transfer, and moving toward performance-based funding.

But getting millions more Americans to earn post-secondary credentials won’t come cheaply. The Comprehensive Grant Program, announced by Biden at the first annual Building a Grad Nation Summit, will award a total of $20 million to individual institutions for “innovative reform practices that have the potential to serve as models for the nation,” according to a Department of Education press release.

If Obama gets his way, other competitive funds will also be up for grabs. The 2012 budget calls for two more programs, including one (at $123 million) aimed at reducing the cost and time to a diploma or increasing completion rates.

States willing to make changes could also be eligible for part of a $50 million pool for so-called “College Completion Incentive Grants.” Much like Race to the Top in the K-12 sector, these grants would be doled out to states that agree to implement certain reforms. With this grant, though, states will not receive funds until after they’ve demonstrated success.

Charter universities: Let the controversy begin

In cash-strapped states where governors are proposing major cuts to services, some public universities that face deep cuts are set to adopt an innovation from the K-12 world: chartering.

A story in Stateline last week reported that several states, including Wisconsin, are proposing to cut loose some of their public universities from certain state regulations in return for less public funding. This means — and here’s what will likely prove controversial — the schools will have more flexibility in setting their own tuition rates.

The University of Wisconsin-Madison could have more freedom to set its tuition under new budget proposals (photo courtesy of Daniel J. Simanek)

The plans sound a lot like the model for K-12 charter schools, which are given more autonomy from the rules that govern regular public schools (although that doesn’t always mean they get less money; in New York City’s case, they get more).

Ohio is also in the process of making the state dollars that universities receive contingent on graduation rates — which sounds similar to the concept of charter schools, which can be shut down if test scores are too low.

The idea of charter universities “will raise questions about the core mission of state universities whose original purpose was to offer an affordable education,” the Stateline article says. That is, if state universities are allowed to set tuition rates, they’ll likely raise them, which could end up reducing the access of low-income students (who tend to do worse academically than their more affluent peers) to higher education. And that could bring the perennial charter-school questions into the world of higher ed: do charters cream the most successful students from the available pool, and do accountability provisions create incentives for charters to do just that?

The ‘untold story’ on federal loans: Delinquency

For years, how college students have fared in repaying their federal loans has been measured by the loan-default rate. U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan made headlines last September with the announcement that the default rate had risen to 7.0 percent for the 2008 national cohort, compared to 6.7 for the previous year — a sign that students are struggling to pay for higher education in tough economic times.

But a new study reveals a more complex picture. For every student who defaults on his or her loan, another two students are delinquent, the Institute for Higher Education Policy has found.

It doesn’t take much to become delinquent on a loan — you just have to miss one or more scheduled payments. If you don’t pay for two months, your delinquency is reported. Defaulting happens once you’ve been delinquent for 270 days.

But, as “Delinquency: The Untold Story of Student Loan Borrowing” highlights, those borrowers have to deal with many of the same consequences as those who default, including poor credit ratings and trouble borrowing in the future.

In all, only 37 percent of borrowers managed to repay their loans on time and without incident. An additional 23 percent used repayment options — deferment or forbearance — to postpone payments.

About 15 percent of students who had taken out federal loans defaulted on them, while another 26 percent became delinquent at some point.

Survey of the American Teacher released

Results of the 27th annual MetLife Survey of the American Teacher were released today. Here’s a sample of some of the findings from surveys with teachers, students, parents and Fortune 1000 executives. You can check out the whole report here.

- Overall, 54 percent of teachers said that “graduating each and every student from high school ready for college and a career is something that must be done as one of the highest priorities in education.” And another 31 percent said it should be done. But it was a higher priority for urban and rural school teachers, with 57 percent of them saying it had to happen, compared to 48 percent of suburban teachers. Similarly, teachers teaching mostly low-income or minority students were more likely to view this as a “must do” rather than a “should do.”

- In middle school, boys and girls aspire to go to college in equal numbers. But in high school, 83 percent of girls plan on getting a college degree, compared to 72 percent of boys.

- The percentage of middle and high school students who intend to go to college is increasing. In 1988, just 57 percent said it was “very likely they will go to college.” Today, that number is up to 75 percent.

- Problem-solving and critical thinking are seen as the most important skills for college and career readiness, with the ability to write clearly and persuasively and the ability to work independently following closely behind. Things that weren’t seen as overwhelmingly important? Higher-level math and science skills and knowledge of other nations and cultures and international issues. Yet, the study also found that “schools with stronger college-going cultures are more likely to emphasize global awareness.”

Questions, investigations of suspicious test scores

Are students at some schools in Arizona, Michigan, Ohio, Colorado, Florida and California suddenly making vast and unprecedented leaps in learning? Or at least in how they are performing on standardized tests?

Perhaps, but it’s not statistically likely, according to a USA Today investigation, supported in part by The Hechinger Report. The lengthy story has already led to at least one review, by the Michigan Department of Education, according to the Detroit Free Press.

The Free Press found improvements at 34 schools statewide so suspicious they raised questions from the department and from the state House Education Committee, which may call for hearings on how Michigan investigates cheating on its elementary and middle-school exams, along with high-school merit exams.

USA Today, according to its series, “used a methodology widely recognized by mathematicians, psychometricians and testing companies. It compared year-to-year changes in test scores and singled out grades within schools for which gains were 3 standard deviations or more from the average statewide gain on that test. In layman’s language, that means the students in that grade showed greater improvement than 99.9% of their classmates statewide. ”

Watch for installments to come.

The evidence disconnect in education policy

Is good evidence winning or losing the battle over education policy? I sat in on an interesting panel discussion on reading last week hosted by the New America Foundation, where the conclusion was, in essence, good evidence isn’t winning often enough. In the case of reading, where there is relatively abundant research on what works, very few school districts and classrooms actually implement tried-and-true methods, the panelists said.

The problem goes beyond reading, of course. The education world is notorious for the relatively weak research base that informs what happens in schools and classrooms. Recently, the Obama administration has tried to encourage more practices based on good research through its Investing in Innovation Fund, where groups and school districts competed for federal money to expand education reform programs that were supported by research.

But shaky or conflicting evidence is still often the norm in many areas of education. Several stories this week highlight this problem: On Monday, Sam Dillon of The New York Times wrote about the debate over class size, which has become shriller as budgets have shrunk and districts are being forced to increase student-teacher ratios. Educators are divided over what the research says on whether small class sizes matter — or matter enough to make up for the extra costs. (See what we’ve written on the issue, here.)

Also in the news, Gothamschools.org highlights a new report that finds that merit pay — a favorite among education reformers, including Education Secretary Arne Duncan — didn’t work to improve test scores in a New York City experiment, and was actually connected with dropping test scores among middle-school students. A Vanderbilt University study in September 2010 found largely the same thing, that offering middle-school math teachers bonuses up to $15,000 did not produce gains in student test scores.

There are many other examples. Does the preschool research show enough of a lasting benefit for children to justify its (often high) expense? As states decide whether to divert more resources to charter schools, which of the various charter studies are to be believed — the big national studies that found that charters are mediocre on average, or the smaller studies that have found that in cities, at least, they perform better than their public school counterparts?

These questions over what policies are supported by research — and which research is best — are likely to get more heated as districts prioritize in tight financial times. Will tighter wallets force schools and policymakers to pay more attention to the evidence to ensure that we get better bang for our buck, or will evidence continue to get short shrift?

The New York Times needs to do its homework

An editorial in today’s New York Times, titled “Fairness in Firing Teachers,” has me wondering whether the Times editorial writers understand much about how teachers — in New York City and elsewhere — are evaluated. The editorial makes some stunning statements that simply don’t comport with reality.

First, there’s this: “Most reasonable people would agree that, when layoffs become necessary, teachers should be let go through objective evaluations of how well they improve student performance, and not merely on the basis of seniority. The problem throughout most of the country is that evaluation systems are not in place. In New York City, only about 12,000 of 80,000 teachers have been evaluated, based on their students’ grades on standardized tests.”

This, the opening paragraph of the editorial, is factually incorrect. It is untrue that “throughout most of the country … evaluation systems are not in place.” Just about every school district in the country has a teacher evaluation system.

The problem isn’t that evaluation systems don’t exist but that most aren’t very good. As The New Teacher Project demonstrated with its 2009 report, “The Widget Effect: Our National Failure to Acknowledge and Act on Differences in Teacher Effectiveness,” most teacher evaluation systems in the U.S. rate the vast majority of teachers — upwards of 99 percent — as effective. So the problem is not that teachers aren’t regularly evaluated — they are — but rather that the evaluations are mostly meaningless.

Also, it’s untrue that “only about 12,000 of 80,000 teachers [in New York City] have been evaluated.” New York City teachers are routinely evaluated by their principals, a point made clear in a different New York Times piece today.

What the Times editorial writers probably meant is that only 12,000 out of 80,000 New York City teachers have value-added scores and thus receive Teacher Data Reports. That’s because value-added scores currently exist only for those who teach English or math in grades 4-8 — hence, just 15 percent of the city’s teachers receive the data reports. But that’s not the same thing as claiming that only 15 percent of the city’s teachers are evaluated.

It’s interesting to note that this sentence would have been correct if a certain comma had been omitted: “In New York City, only about 12,000 of 80,000 teachers have been evaluated, based on their students’ grades on standardized tests.” Kill the comma between “evaluated” and “based,” and you suddenly have a true statement. Keep the comma and it’s inaccurate. That’s the power of punctuation, folks.

The more important point here — which the editorial writers fail to make — is that 85 percent of New York City teachers aren’t teaching subjects or grades for which value-added scores can currently be calculated. Eighty-five percent!

Another statement worth scrutinizing is this: “teachers should be let go through objective evaluations of how well they improve student performance.” There seems to be an implicit assumption in the editorial that a system of “objective evaluations” exists but that some parties — teachers? their unions? — oppose it. It doesn’t take too much reading between the lines to see that the editorial is suggesting value-added scores of teachers are these “objective evaluations.” (Otherwise, why the reference to 12,000 out of 80,000 teachers in New York City having been “evaluated”?)

Actually, no “objective evaluation” system exists. Not even those that rely heavily on value-added scores.

Plenty of evidence — anecdotal (see Michael Winerip’s piece in today’s Times) as well as hard research — indicates that constructing a value-added model requires lots of decisions, the most important of which is the inclusion or exclusion of certain variables. These decisions are, of course, inherently subjective. The New York City model contains 32 variables.

Whether the end product of a subjective process like constructing a value-added model can be called “objective” is doubtful.

What is less doubtful is that value-added models occasionally misidentify high- and low-performing teachers, as those both in favor of and opposed to using student test scores in teacher evaluations agree. How frequently such mistakes happen is a matter of heated debate but that they do isn’t really contested. With that in mind, it seems a stretch to call any system of evaluating teachers “objective.”

Objectivity in evaluations — of anything or anybody, not just of teachers — is a myth, even if the evaluations are rooted in objective-looking numbers. One can certainly make the case that value-added scores are less subjective than administrators’ observations, but that’s not quite the same thing as saying they are entirely objective.

The Times editorial writers call for the New York state legislature to “make sure that the scoring system weighs student performance [in teacher evaluations] most heavily.” What they seem blind to is the fact that measuring student performance in any kind of meaningful way is an art, not a science, and doing it well means using multiple measures (not just standardized test scores).

We remain far from a system that measures student or teacher performance well. So while it is easy for politicians and pundits — from Mayor Michael Bloomberg and New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie to Michelle Rhee and the New York Times editorial board — to call for an end to seniority considerations in layoff decisions, it’s not at all clear what should be used instead of seniority (especially in the short-term, with layoffs imminent). The alternatives — like a robust evaluation system that could accurately and comprehensively capture educator effectiveness — exist more in theory than in practice.

Wisconsin Gov. Walker was pro-teachers union before he wasn’t

Only a few days before Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker started a war with organized labor, he was effusively praising the state’s teachers and their union, the Wisconsin Education Association Council. On Feb. 8th, WEAC proposed two big reforms that it had previously opposed: the creation of a statewide system for evaluating teachers that took into account their students’ gains in achievement, and a compensation system that rewarded performance.

The next day, Walker and Secretary of Education Arne Duncan were asked to react to the WEAC proposals on the Wisconsin Public Radio show hosted by Joy Cardin. (Search for Arne Duncan and it will be the first one to show up. ) “It’s great,” Walker said. “We should be able to reward teachers who excel and there are many, many, many teachers across the state who excel,” he said. “For the state’s teachers union to be willing to talk about pay for performance and a legitimate way for teachers to be assessed, I think it’s … exceptional … a good sign.”

Even as he was praising the union, however, he was about to go on the attack. He soon introduced a budget package that would essentially restrict collective bargaining in the state only to wages.

Duncan, who has been critical of Walker’s move, recalled that radio interview at a breakfast with bloggers in Washington, D.C. this week. In the interview, Duncan had said “WEAC is showing tremendous courage, it’s the right thing for children, it’s the right thing for teachers, it’s the right thing for the profession and where you have leaders with courage willing to step out there and, frankly, probably take some pretty significant heat internally, we need to reward that … and recognize it.”

What you don’t want to do, Duncan told the bloggers, “is hit them with a hammer,” implying that Walker had squandered an opportunity to collaborate on issues that would directly affect the quality of teaching in the state.

Duncan said he is “not in favor of collaboration for collaboration’s sake … I’m not about kumbaya. It’s about doing things to get better results for kids.” Collective bargaining isn’t going away, and he said it “can and will be a tool for improving student achievement.”

But that won’t happen in Tennessee, Ohio, Indiana and other states that are trying to eliminate collective bargaining or limit negotiations to wages.

A version of this post first appeared on Education Sector’s “The Quick and the Ed” blog on March 4, 2011.

Could “micro-charters” be a way to fuel charter-school growth?

Charter schools are booming nationally. With 443 charters opening in 2009-10 alone, they grew 6.2 percent during that school year, according to the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools.

But this growth isn’t enough, some say — while others are quick to remind us that not all of the new charters are of high quality. Oft-cited research from the Center for Research on Education Outcomes (CREDO) at Stanford found that only 17 percent of charter schools in the country significantly outperformed their traditional public-school counterparts. These top charter schools reached about 272,000 children in 2009-10, according to the Progressive Policy Institute. To put that in perspective, about 50 million children are enrolled in U.S. schools — 10 million of whom live in poverty.

“The number of children served by the best charter schools is far to low,” concludes a new report by the Progressive Policy Institute. The paper, “Going Exponential: Growing the Charter School Sector’s Best,” outlines several ways that high-quality charters can grow even faster based on successful private-sector practices.

Among the most intriguing ideas are the concepts of “micro-reach” and “micro-chartering,” in the words of authors, Public Impact’s Emily Ayscue Hassel, Bryan Hassel and Joe Ableidinger.

In “micro-reach,” an existing charter management organization (CMO) starts a relationship with a teacher who works in a regular school district but who wants to use the CMO’s program in his or her classroom and partake in the CMO’s professional development. Bryan Hassel compared it to how Starbucks sells its products not just in its own stores but also in grocery stores, on airplanes and at the local Barnes & Noble. It’s a way to “reach customers without setting up a whole new school,” he said.

In the “micro-chartering” scenario, an individual teacher could get a charter for his or her classroom. Or a community organization with 40 kids in its part-time after-school program could get a micro-charter to work with them on a full-time basis.

Such arrangements would allow for “much more [and] quick accountability,” Hassel said. “Since it’s not a whole school – that whole apparatus – it’s not as big of a deal to withdraw the charter.”

Assignment memo: The growing problem of the Hispanic achievement gap

Reporter Sarah Garland is working on a story about achievement gaps:

California has one of the worst gaps in the nation between Hispanic and white students in reading. Only 12 percent of Hispanic fourth graders were proficient in reading in 2009 on the National Assessment of Educational Progress, known as the Nation’s Report Card. The gap between Hispanic and white students — 47 percent who were proficient on the test in 2009 — actually grew slightly over the past decade.

Already, Hispanic students are a majority in the state, up from just a third of the student population 15 years ago, and their numbers are rising quickly. The number of English learners — the vast majority of them Hispanic — has also grown. Research has shown that students who don’t reach the benchmark of reading by third grade are at much higher risk of dropping out of high school later on, meaning California is on track to host millions of dropouts in the coming years. With college, not high school, increasingly the ticket to a decent job, the trend could spell economic disaster for a state that’s already deep in a financial crisis.

What’s being done to help Latino students get ready to read by age 8?

What does this mean for the future of the state as the Latino student population grows even larger? What can be learned from other large states with significant Latino populations where gaps are closing more rapidly?

Have ideas for the story? Know a good source? Got a question you’d like seen answered in the story? Add them below and we’ll throw them in the mix.