The Hechinger Report celebrates its first birthday

A year ago today we officially launched The Hechinger Report, and so it seems as fitting a time as any to reflect on our work in the past 12 months.

In May 2010, The Hechinger Report was a theory backed by confidence but not evidence. The theory was that news organizations—amid cutbacks and dramatic changes in the industry—would be eager to collaborate in a variety of ways with a nonprofit, nonpartisan news outlet dedicated to covering education.

Flash-forward to May 2011, and the evidence is unambiguous: there’s a very strong appetite for the coverage we can and do provide. Our work has since appeared in dozens of the nation’s most prominent publications, including the American Prospect, Boston Globe, Chicago Tribune, Chronicle of Higher Education, Connecticut Mirror, Education Week, Huffington Post, Indianapolis Star, Los Angeles Times, the McClatchy chain, Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, New York Times, Philadelphia Inquirer, Providence Journal, Seattle Times, Texas Tribune, U.S. News & World Report, Washington Monthly, Washington Post and WBEZ-Chicago.

We’ve also had a hand in important, controversial coverage—most notably, in the “Grading the Teachers” series last fall with the Los Angeles Times, which sparked a national debate about how teachers are evaluated, and in USA Today’s recent series, “Testing the System,” which investigated suspicious test scores in six states and the District of Columbia.

We are proud to have been part of the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel’s eight-part “Building a Better Teacher” series, which won first prize in the Education Writers Association’s 2010 National Awards for Education Reporting.

Finally, The Report’s most ambitious project to date has been the creation of a national reporting collaborative to analyze the impact of the $100 billion federal stimulus on public education. With assistance from EWA, we identified 36 news outlets in 27 states that were willing to partner with us on this project. Interviewing scores of students, teachers, researchers and education officials at all levels of government, participating reporters set out to determine how the nation’s schools were actually spending the money and whether the changes it has sparked are likely to last. In the end, 21 news organizations with a total circulation of more than 4 million published stories that drew on the project’s work. Links to all of the coverage can be found both here and here.

And we’re just getting started! Here’s to many more years of compelling education coverage! To all of our supporters and collaborators, a hearty thank you for your unwavering belief in our model and our work.

College: Worth it, or worthless?

Is a college degree worthless? An article this week in New York magazine poses this question, which has generated lots of commentary and controversy in recent years, what with The Atlantic’s anonymous professor tell-all and a series of books (including one whose findings we detailed here).

New York magazine’s “The University Has No Clothes” is a vehicle for two anti-college pundits who have railed against the college industrial complex — as well as an opportunity to feature a photo of several nearly naked and very fit 20-somethings, in case the pundits’ contentious claims don’t draw sufficient attention.

That’s unlikely, however. In the education world, getting increasing numbers of young people to and through college is an Obama administration goal that has been embraced by everyone from union heads to charter-school leaders. But there is a brewing sense of crisis over what happens to young people once they arrive at college. As New York magazine points out, many students drop out, most leave with enormous amounts of debt, and those who do graduate are not always prepared to work in the real world.

That’s unlikely, however. In the education world, getting increasing numbers of young people to and through college is an Obama administration goal that has been embraced by everyone from union heads to charter-school leaders. But there is a brewing sense of crisis over what happens to young people once they arrive at college. As New York magazine points out, many students drop out, most leave with enormous amounts of debt, and those who do graduate are not always prepared to work in the real world.

Does this mean we should do away with college, or that college – like many have argued of K-12 education – is overdue for some major reforms?

This isn’t a question that is being asked only here in the United States. Around the world, countries that are competing with America for global preeminence are trying to figure out how to improve the skills of their future workforces. Most have decided that college is indeed worth it. At the same time, what the “college experience” actually entails is changing — sometimes radically.

Stay tuned. Here at The Hechinger Report, we will be exploring these questions in depth in the coming months.

How to get those civics scores up? Video games!

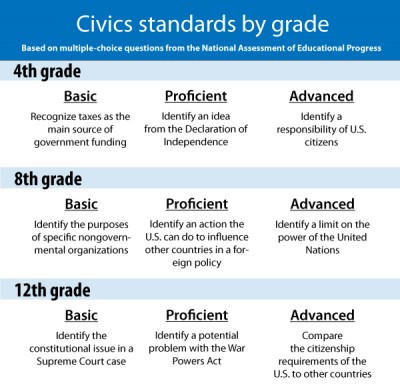

So the release of the 2010 NAEP scores on civics shows there’s lots of room for improvement. But how to get better?

An outfit called iCivics — the brainchild of former U.S. Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor — uses video games to teach students about the rights and responsibilities of citizenship.

iCivics has more than a dozen different games on civics that (fairly subtly) teach kids about everything from volunteering to being the president to earning citizenship. The games are all browser-based and available free online.

Here are a few examples:

- Executive Command is all about being the president. Players do everything from sign bills, speak to Congress and manage wars. While there is blatant civics teaching going on at times, the core lessons are actually grounded in the gameplay. You learn that the president is very busy (you rarely have time to pause for a few seconds) and has lots of different jobs (managing the military, signing bills, getting bills enacted, international diplomacy). Even if players skim over the more obvious teaching moments, they cannot avoid learning these core lessons because they’re built around the gameplay.

- Immigration Nation teaches kids about the various ways people can get into the U.S. by having them direct different boats to different docks. The game is simple, surprisingly fun and quick to learn. Like most good games, it lets players jump right in with little explanation and slowly adds more complexity a bit at a time. By the end of the game, you’ve got full mastery without ever feeling like there was a “teaching” moment.

- Supreme Decision is a bit more complex and a lot less interactive. Players have to listen to various arguments about a U.S. Supreme Court case and then answer several questions. This game presents the greatest opportunity for boredom, as there isn’t much gameplay involved. But the core case is focused on a topic that might interest kids — whether wearing a band T-shirt is protected speech under the First Amendment. Plus, players eventually get to decide the outcome of the case, which can’t hurt.

A mixed picture on nationwide civics exam

When it comes to how much our country’s students know about civics, the results are decidedly mixed. Scores from the National Assessment of Educational Progress 2010 civics test, released today, reveal that fourth-graders turned in a record performance. But there was no statistically significantly change for eighth-graders, and 12th-graders actually did worse this time than they did when the test was given in 1998 and 2006.

NAEP — commonly known as the Nation’s Report Card — tests students on “civic knowledge, intellectual and participatory skills, and civic dispositions” in this particular exam, with both multiple-choice and open-ended questions.

Twenty-nine percent of fourth-graders were proficient or advanced in 2010, along with 23 percent of eighth-graders and 28 percent of 12th-graders.

You can check out the full report for more details. Here’s a sampling of some of the interesting findings by grade-level:

- The gaps between black and white students and between Hispanic and white students have narrowed significantly among fourth-graders, although a gap certainly remains. On the other hand, the disparity between male and female students has widened, with girls outscoring boys by seven points, up from two points in each of the previous rounds of the test.

- The most-taught topic in eighth grade was the U.S. Constitution, with 82 percent of students saying they studied it during the school year. Runners up were Congress, with 78 percent of students saying they learned about it that year, and “political parties, elections, and voting” at 75 percent. By contrast, only 40 percent of eighth-graders reported studying other countries’ governments, and only 33 percent said they learned about international organizations.

- Also in eighth grade, scores went up across income levels, but they increased the most for students who qualify for reduced-price lunch. These students saw their scores jump five points, as opposed to a three-point increase for both those eligible for free lunch and those not eligible for either.

- While twelfth-grade scores declined overall, two groups saw a slight increase from 2006: Hispanics and American Indians/Alaska Natives.

- Though the gender gap widened in fourth grade, it disappeared in twelfth grade — but not because boys were catching up. Both males and females scored worse than in 2006, with males dropping by two points and females by four.

Walcott and Bloomberg push for school “choice”

Hechinger reporter Sarah Garland has another collaboration with Capital New York, this time looking at school choice in the city. The story opens with…

Dennis Walcott, the new chancellor of the New York City public schools, said recently that he would push to open more single-sex schools in the city. He’s a “big believer” in these schools he told the New York Post, and, more importantly, he’s “a big believer in options.” He thinks “people should have that choice.”

Her piece explores the rise of smaller schools of “choice,” such as charter schools, and how some of them haven’t produced better results than traditional public schools.

Read the full story at capitalnewyork.com.

A closer look at schools receiving $3.5 billion to improve

Education Sector released “A Portrait of School Improvement Grantees” today, with an interactive map that allows readers to sort federal grant recipients by state or improvement model. The map provides details on the grants that have gone to over 800 struggling schools, serving nearly 600,000 students, across the nation. The Obama administration has set aside $3.5 billion for this work.

States identify their lowest-performing schools and then ask districts to apply for the grant money, which then goes to individual schools over a three-year period. Each school must follow one of the four improvement models specified by the U.S. Department of Education:

- Turnaround Model: Replace the principal, screen existing school staff, and rehire no more than half the teachers; adopt a new governance structure; and improve the school through curriculum reform, professional development, extending learning time, and other strategies.

- Restart Model: Convert a school or close it and re-open it as a charter school or under an education management organization.

- School Closure: Close the school and send the students to higher-achieving schools in the district.

- Transformation Model: Replace the principal and improve the school through comprehensive curriculum reform, professional development, extending learning time, and other strategies.

The last of these — “transformation” — has proven most popular, with 73 percent of SIG recipients choosing it, according to Ed Sector’s analysis. “Closure” and “restart” were significantly less popular options, with only two and four percent of grantees, respectively, choosing to employ them. For a detailed look at a school that has gone the rare “restart” route, see our story from February 2011 on Mastery Charter Smedley Elementary in Philadelphia that also appeared in Politics Daily.

Among the other findings of Ed Sector’s analysis: “while most federal dollars are usually funneled to elementary schools, nearly half of the SIG grantees are high schools—signaling a shift in federal spending and an urgency to reform America’s ‘dropout factories.’ Many of the SIG grantees are low-performing urban schools, but there is a surprising amount of diversity: 18% are rural, 17% suburban, and the grantee list includes dozens of charters and many more magnet schools.”

Does lecturing trump hands-on learning in the classroom?

For decades, many have frowned upon lecture-style classrooms in the U.S., where the teacher stands at the front of the classroom while all students listen and take notes. Instead, there’s been an emphasis on hands-on learning and problem-solving, where students learn by doing the work themselves.

But a working paper from the right-leaning Program on Education Policy and Governance at Harvard — summarized in the Summer 2011 issue of Education Next — suggests we shouldn’t be so quick to condemn the “sage on the stage” approach to teaching in favor of the “guide by the side” approach.

Researchers Guido Schwerdt and Amelie C. Wuppermann used middle-school data from the 2003 Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) to look at both student performance and how teachers reported using classroom time (whether on lecturing, guiding students through problems, or having students work on problems by themselves). They found that in both math and science, the more time teachers spent lecturing, the higher their students scored on TIMSS.

Higher-achieving and “more-advantaged students” benefit the most from an emphasis on lecturing, according to the working paper, while there’s no evidence to suggest that low-achieving students are disadvantaged by lecturing.

Of course, there are other things that can have an impact on these TIMSS scores, such as the depth of the curriculum, the rigor of the standards and the sequence in which things are taught. It’s no secret that higher-performing countries tend to have very different approaches to teaching math and science than lower-performing countries.

The researchers didn’t make any sweeping conclusions, though: “Given the limitations of our data, our finding that spending increased time on lecture-style teaching improves student test scores results [sic] should not be translated into a call for more lecture-style teaching in general,” they wrote. “But our results do suggest that traditional lecture-style teaching in U.S. middle schools is less of a problem than is often believed.”

Why are video games so good at teaching?

Eduptopia has a great post up by Dr. Judy Willis that explains some of the science behind why video games are good at teaching kids.

Basically, the brain encourages kids (and adults) to make correct decisions or predictions and rewards us with dopamine, which triggers a powerful sense of pleasure/satisfation. This rush helps encourge people to build skills.

So why don’t kids get a dopamine rush when they finish a big test or turn in an important project? Willis explains:

“In humans, the dopamine reward response that promotes pleasure and motivation also requires that they are aware that they solved a problem, figured out a puzzle, correctly answered a challenging question, or achieved the sequence of movements needed to play a song on the piano or swing a baseball bat to hit a home run. This is why students need to use what they learn in authentic ways that allow them to recognize their progress as clearly as they see it when playing video games.”

What is great is that the brain actually makes kids want to take on harder and harder problems when playing video games, Willis says.

“It may seem counter intuitive to think that children would consider harder work a reward for doing well on a homework problem, test, or physical skill to which they devoted considerable physical or mental energy. Yet, that is just what the video playing brain seeks after experiencing the pleasure of reaching a higher level in the game.”

In case you missed it, we had a post last week on researcher James Gee’s recent presentation at a MacArthur Foundation seminar on digital technology and learning. It was a fascinating run down.

As more high-schoolers complete rigorous curricula, achievement gaps remain

The National Assessment of Educational Progress offered insight into our country’s school system today with the release of its 2009 High School Transcript Study. The report, which scrutinized the transcripts of 37,700 graduates from the Class of 2009 at 610 public and private schools across the nation, contains few surprises. But it does stand as a reminder of the country’s progress — as well as how far it has to go before every student is “college or career-ready.”

Sixteen percent of high-school students completed a “standard” curriculum, with four credits of English and three credits each in social studies, math and science. Forty-six percent of graduates navigated a “mid-level” curriculum that included the standard requirements but also mandated that two of the math courses be geometry and Algebra I or II and two of the science courses be biology, chemistry or physics. A mid-level curriculum also has a foreign language requirement.

Compared to years past, more students pursued a “rigorous” curriculum: four credits in English, four credits in math (through or beyond pre-calculus), three credits in social studies, three foreign-language credits, and courses in biology, chemistry and physics. In 1990, just five percent of U.S. high-school graduates completed such a sequence. By 2009, the number had risen to 13 percent.

Over the same time period, the percentage of black students completing a rigorous curriculum tripled from two to six percent. For Hispanics, the percentage quadrupled, from two to eight percent.

For Asians/Pacific Islanders, the percentage of students pursuing a rigorous curriculum surged from 13 to 29 percent.

Though the overall picture seems brighter now than it did two decades ago, racial gaps still exist — both in the percentages of students taking more rigorous curricula and in performance on NAEP exams. For instance, white students taking rigorous curricula scored, on average, 191 on the 12th-grade NAEP test in mathematics, compared to an average of 198 among Asians/Pacific Islanders. Black students averaged 167, while the average for Hispanic students was 172.

Still, black and Hispanic students who enrolled in rigorous classes performed better on NAEP than their white peers who followed a “mid-level” curriculum.

Check out the full report here.

What video games can teach us about the educational process

Looking for a new model of education that could eliminate the need for traditional testing while also encouraging problem-solving and guaranteeing that students will be fluent by the time they finish their lessons?

Most kids are already very familiar with this very system—while playing video games. Researcher James Gee recently gave a run-down on the ways video games can be harnessed for educational purposes at a MacArthur Foundation seminar on digital learning in New York City.

Game-design companies do a good job of educating players quickly and thoroughly. They have to, according to Gee. “If [the players] don’t learn it, they return it,” he said.

One way designers accomplish this is by providing needed information “just in time” for the player to use it in the game world. Or they make it available on demand, like the strategy game Civilization, where players can access a “civilopedia” that contains details on the various game concepts, civilizations and units featured in the game.

“In school, information is given to you whether you want it or not and never just in time,” Gee said. “You’re not going to use the 500 pages until you finish them, and by that time you can’t remember what was on the second page.”

Games also allow players to start playing before learning any of the concepts, Gee noted. “Games are based on performance before competence,” he said. One example he cited is a game that allows students to undertake urban planning. The game includes 350 professional codes that students must use.

“School would say, ‘Okay, we’re going to memorize 350 codes and then we get to play the game.’ ”

In the world of video games, by contrast, students are able to dive in right away. “The kid has used them so many times by the end of the game they know all 350 codes,” Gee said. That kind of educational process eliminates the need for traditional testing, according to Gee.

He gave an example of a boy playing the popular science-fiction shooter game Halo on “nightmare” level (the highest difficulty setting). Once the boy beat the game—after 40+ hours of game time—there was no need for testing, he said.

“The test was what he just did,” Gee said.

Many games also offer in-depth statistics and graphics that detail a player’s performance with multiple variables tracked throughout his or her entire playing time. It’s the kind of rich data educators would love to have.

“No school does this,” Gee said.

And there are other surprising ways that video games can promote learning:

- Gamers regularly become so enamored with a game that they develop “passion communities,” Gee said, in which they study the game in-depth, modifying or expanding it. As an example, Gee pointed to fans of the physics-based game Portal, where some gamers have analyzed the physics of the game in great detail.

- Gamers can create challenges for one another that create learning opportunities. Gee cited an example focused on the popular life-simulation game The Sims. Players were challenged, in one case, to play the entire game as an impoverished single parent and then create a graphic novel about their experiences. “That sounds like a pretty good social-sciences assignment, right?” Gee said.

Worried about violence in video games? Gee tackled that as well, pointing out that the correlation between television and violence is much stronger than that between video games and violence.

“So if you’re worried about video games, turn off the television first.”

Both video games and television pale in comparison to the written word when it comes to inciting violence, Gee added. “If we took the number of people killed because of a video game … the number of people killed would fit comfortably at two tables. If we took the number of people killed because of how someone read a book, like the Quran or the Bible or The Turner Diaries … we could not fit them in the state [of New York].”