The American Jobs Act: Does it have the answers?

President Barack Obama and Education Secretary Arne Duncan (Photo by Obama-Biden Transition Project)

Mixed reactions are emerging to President Barack Obama’s education pledges in his introduction of the American Jobs Act last night, outlined further by Secretary of Education Arne Duncan on Friday afternoon.

Duncan, currently on a tour of four cities, says he’s seen ballooning class sizes and major cuts to art programs and extracurricular activities. “To have a chance like this to reverse those trends and make the right investments, both in terms of teachers but also the capital side where there’s so much need,” said Duncan.

The $447 billion bill would include $60 billion in additional stimulus dollars to “modernize” up to 35,000 schools and help, as Obama said in his speech, “put teachers back in the classroom where they belong,” by saving the jobs of 280,000 teachers.

Some reactions:

– The modernization aspect of the proposal has garnered some support. Bob Wise, president of the Alliance for Excellent Education, said “President Obama’s school modernization proposal would help schools develop the technological infrastructure to strengthen instruction and prepare our students for success in college and a career. This investment in schools today will pay large dividends in the future.”

– Others are skeptical of both the bill itself and its likelihood of getting through Congress, stating that Obama couldn’t pass a similar bill in a Democratic-dominated Congress last year. Skeptic Rick Hess stated on his blog that the new stimulus package is “merely another push to kick the can down the road on hard but important choices,” and will serve as only a band-aid for larger systemic problems.

– Alyson Klein of Education Week, who also believes the bill will have a hard time passing Congress, wrote on her blog, “Administration officials have said this jobs package has pieces that have garnered broad bipartisan support, but the education piece seems more like a re-election campaign promise than a serious legislative proposal.”

– Chris Tessone wrote on the blog Fly Paper: “There is no reason to expect anything but business as usual from another round of subsidies. When the new money goes away, districts will still not have adjusted to the new normal, to their students’ detriment. More subsidies just protect the status quo at great expense to taxpayers.”

Echoing Obama’s message, Duncan and White House Domestic Policy Council Director Melody Barnes stressed bipartisan support of the ideas in the legislation that will be introduced next week.

Whether the bill will have any success getting through Congress remains to be seen, but it seems clear that this is a big agenda for the Obama administration. Please share your thoughts on whether you think the American Jobs Act will help advance quality education in America.

Republican debate: Who said what about education?

Republican presidential candidates sparred over the economy, health care and immigration in last night’s debate at the Ronald Reagan Library. Like in the previous debate, only two candidates were questioned about education policy, and neither took the opportunity to say anything groundbreaking.

Texas Gov. Rick Perry, when asked about the recent $5 million budget cuts he’s made to public education, defended them, saying “the reductions we made were thoughtful reductions.” He declined to elaborate on the logic behind the move, though. Instead, as he has many times so far on the campaign trail, Perry touted his record of improvement in the state’s schools, citing graduation rates that have climbed to 84 percent.

What do they believe?

While the Republican candidates for president may not have said much about education at Wednesday’s debate, there is plenty we know about their stances on education.

Check out Hechinger’s rundown of all of the major candidates and what they’ve said about their plans for education.

According to the Texas Department of Education, graduation rates for the 2009-2010 school year were, in fact, slightly above 84 percent. But by another measure, the State Rankings 2009, the state ranked 43rd out of 50 with a graduation rate of 61 percent.

Graduation and dropout rates are tricky statistics that can be calculated several different ways, leading to such discrepancies. Just last year, when Texas reported a 11 percent decline in its drop out rate, the Hechinger Report, among other news outlets, examined why there may be reason for skepticism about the data. Regardless of how many students graduate, college-readiness has also been called into question: Only four state universities out of 38 institutions in the Lone Star state graduate more than 30 percent of full-time students within four years.

Newt Gingrich, also specifically asked about education, repeated what he’s said before; he supported Race to the Top and is pro-school choice. Again, he proposed a Pell grant system for the K-12 level, where all parents would be able to get money to send their children to whatever school they pick.

“If every parent in America had a choice,” he said, talking about charter schools he’s visited in Philadelphia. “You’d have dramatic opportunity.” Gingrich, like many of his competitors in the Republican race, has depicted charter schools as a better alternative to regular public schools, despite research that shows that this isn’t always true.

Notably, Gingrich also specified that schools should be required to report their scores. Transparency – or lack there of – has been a point of contention in the charter debate thus far, and Gingrich hinted that he would hold charter schools accountable for results.

Education popped up a few other times throughout the debate. Bachmann talked about her political roots as a education activist and spoke of the need to localize education saying “we have the best results when we have the private sector and the family involved.”

Romney, when answering a question about immigration reform, mentioned the importance of not having tuition breaks for illegal immigrants. Currently, nine states, including California, Texas and Utah, allow illegal immigrants to qualify for in-state tuition at public universities, sparing them from the tuition fees of out-of-state students.

And Ron Paul continued to be anti-big government without discrimination, saying that the decision to serve hot lunches at school for poor children should be left up to local and state governments – not Congress.

Is technology in the classroom a bust?

The New York Times ran a front-page piece this past weekend on the fact that test scores don’t seem to be getting a boost from the billions being spent on new technology in the classroom. The education-policy world has been all over the story, with some knocking The Times and reporter Matt Richtel. Others are saying the story is an important reminder that technology isn’t a cure-all.

Here’s some of the reaction:

Peter Meyer, a fellow at the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, calls the article a “wakeup call for the digital revolution” and warns that the real emphasis should be on curriculum.

“…as happened to the charter school movement, which spent lots of time and energy debating the chartering process and defending it in the face of frequent lackluster performance numbers, the technological classroom is late to an appreciation of the essential elements of education; mainly, the importance of knowledge. What should our kids know?”

Tom Vander Ark defends digital learning on his blog, saying Richtel chose to cherry-pick weak examples of technology use in the classroom.

“It’s easy to make sweeping statements about the past and prop up critics. Richtel knows well the case for digital learning; he just chose to leave it out.”

MediaShift says Richtel buried the lede of the story, which is that standardized test scores can’t accurately measure the value of technology in the classroom.

“Richtel also neglected to point out an important piece of the puzzle: that standardized assessments are in the process of being recreated. The tests will use technology in both administering and scoring and will measure ‘performance-based tasks, designed to designed to mirror complex, real-world situations,’ according to the New York Times.”

Cathy Davidson at HASTAC also lays part of the blame on outdated tests, but then goes on to say schools ought to be investing money in training teachers to use technology.

“No school should invest in technology without investing in substantial, dedicated retraining of its workforce—which is to say its teachers. If IBM pays the equivalent of $1700 per employee per year to help them keep abreast of new technology, new methods, new tools, shouldn’t we be investing that kind of funding in supporting the professional development of our teachers who are training the next generation of IBM workers?”

Kaplan’s Chief Learning Officer Bror Saxberg says the problem isn’t with technology or the tests, but rather that “we’re not thinking about how to improve learning based on what’s known about learning, and then applying technology to make it faster, cheaper, easier, and data-rich.”

“Even worse for students, we may be short-changing their futures this way. Instead of focusing our efforts (including technology) on mastering sometimes challenging skills that are essential in the competitive world they’re about to enter, we’re getting them to spend that time on things that we think are ‘cool.'”

Jonathan Schorr at the NewSchools Venture Fund says the central question of the story — is technology good? — is too broad. It’s akin, he says, to asking “how good are restaurants?” and then looking at overall reviews for all restaurants.

“As a guide to the future, the better question is, are there models that make innovative use of technology and offer transformative potential? The answer is an emphatic yes; there are plenty of examples.”

Richard Lee Colvin of Ed Sector (and formerly of The Hechinger Report) knocks The Times for assigning a tech reporter rather than an education reporter, and highlights a few questions the story missed.

“Q. Does the technology make it easier for teachers to understand students’ thinking? Where they need extra help?

Q. Does it make it easier for students to learn from one another, perhaps using social media?

Q. Does it help students learn basic material more quickly so that more class time can be devoted to in-depth discussions and applications of knowledge to solve problems?”

Atlanta area teacher Robert Ryshke blogs about the five things he thinks we should invest in–and technology is #5 on the list. At the top of his list? “Improving what we teach students” and “Supporting the development of excellent teachers.”

Will this generation be the first to be less educated than their parents?

Interviewed by reporter Jon Marcus for his story, Jake Boyd took five years to finish a criminal-justice degree while working two jobs at the same time he was going to classes. (Photo by Rob Widdis/McClatchy Tribune)

In July, reporter Jon Marcus wrote a piece for The Hechinger Report looking at President Barack Obama’s college graduation goal and how much progress has been made toward reaching it.

Now he’s been interviewed by Boston NPR’s Here and Now program about the fact that this generation of Americans could be the first in history to be less educated than their parents.

From the Here and Now site (where you can listen to the full interview):

It’s back to college time and more students than ever are attending this year.

College enrollment has been trending up for over a decade and according to a new study by the Pew Research Center, it’s now at a historic high. In 2010, the last year for which statistics are available, there were 12 million students in college between ages 18 and 24.

Now here’s the “but.”

For every five students who start in community college, only one finishes within three years, even though community college programs are supposed to be two years or less.

The numbers at four year colleges are not much better — only around half the students who enroll manage to get their Bachelors’ degrees in six years.

On the chopping block: District reforms

Many school districts have now hit the so-called “funding cliff”—and it’s rapidly approaching for many others. Money from 2009’s American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) helped many school districts counteract budget cuts, enabling them to hold on to jobs and buy supplies and equipment. But that money is running out—or already gone—which leaves districts in perilous positions.

A survey released earlier this summer, by the Center on Education Policy in Washington, D.C., found that 70 percent of school districts experienced funding cuts for the 2010-2011 school year, and 84 percent anticipated them in the coming year.

This could mean bad news for education reformers and imperil the reforms spreading across the country. Forty-nine percent of school districts with funding decreases indicated they’d have to slow progress on planned reforms, with an additional 17 percent postponing or stopping reforms all together. Only 16 percent of the districts facing cuts anticipate not having to change their reform plans for financial reasons.

The survey found that many districts staring down funding shortfalls had yet to decide what to do about reforms in the 2011-2012 school year, but just 6 percent predicted they’d be able to carry reforms out with little or no impact from budget cuts.

Of course, everything from teaching positions and professional development to facilities funding will be on the chopping block as school districts grapple with the end of the stimulus money—just as many people predicted back in 2009 when they pointed out that the funds weren’t a long-term solution.

But this issue is worth keeping an eye on: with less and less public money to devote to it, what’s next for the country’s education reform?

Do early graduation programs really save states money?

Earlier this year, The Hechinger Report took a look at an increasingly popular method of reforming high schools: providing a scholarship to a state public university to seniors who graduate in under four years. Indiana passed such legislation in April, and, according to a policy brief recently released by Jobs for the Future, similar laws are in the works in Illinois, Kansas, Kentucky, Minnesota, Missouri and Nevada.

On the surface, this kind of legislation can seem like a no-brainer. States often still give high schools a percentage of the money they would have received anyway, while lowering the state’s overall cost per student. Such programs promote college enrollment and can potentially eliminate a financial barrier to higher education—not to mention that many people contend senior year is a waste of time, with students having already passed the tests they need to graduate and having fulfilled other requirements.

But Jobs for the Future warns that such legislation must be well thought out and its goals well-defined to be beneficial to students and state budgets. Say, for example, an early graduation law is passed in the hopes of improving college access. “Unless scholarships are targeted to low-income students, higher income students will benefit disproportionately because they are more likely to be on an accelerated academic path,” the report says. “This approach is also unlikely to significantly increase the rate at which underrepresented students enroll in college unless accompanied by academic preparation strategies.”

Many of the people with whom I spoke for my earlier article about Indiana agreed that in order for an early graduation program to be successful, there had to be solid communication between high schools and universities. As it stands right now, many seniors nationwide graduate ill-prepared for college and have to take remedial classes (which don’t typically earn them any college credit). Skeptics of the early graduation trend sweeping the country would argue that senior year need not be done away with completely, but rather reformed to help prepare students better for college.

Not only does sending students off to college ill-prepared seem to do them a disservice—many students who are placed in remedial classes drop out before getting to real coursework—it’s also a financial drain on the system. It’s another reason to exercise caution before passing an early graduation bill, according to Jobs for the Future.

“If early graduation policies do nothing to increase the college readiness of targeted students, then the state risks sending more unprepared students to college—only faster. That would likely lead to increased remediation in college and lowered completion rates. The short-term benefits of speeding students through high school will be offset by the increasing costs of remedial education and the risk of higher non-completion rates in college.”

New poll: Public trusts teachers, likes technology and school choice

A new public opinion poll on the nation’s public schools reveals a number of interesting findings. The poll, conducted every year since 1969 by Phi Delta Kappa and Gallup, asked 1,000 people about a variety of education topics—from trust in teachers to the use of technology in classrooms.

You can find all of the poll’s results here, but we’ve distilled the essentials for you:

Most people trust public-school teachers and want them to have more freedom in the classroom. Even though a solid majority (68 percent) of respondents said most of the news they hear about teachers is bad, an even higher percentage (71 percent) said they trust public-school teachers to do their jobs. And more still—73 percent—said teachers should be given greater flexibility and not have to follow a strict curriculum.

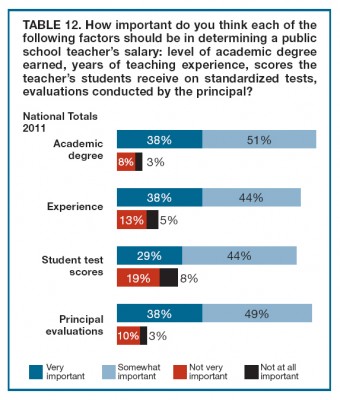

Test scores aren’t the most important thing when it comes to teacher compensation and layoffs. In determining a teacher’s pay, respondents said academic degrees, principal evaluations and a teacher’s experience are more important than test scores. The use of test scores was seen as more appropriate in deciding which teachers to lay off, coming just behind principal evaluations as the most important factors to consider.

Test scores aren’t the most important thing when it comes to teacher compensation and layoffs. In determining a teacher’s pay, respondents said academic degrees, principal evaluations and a teacher’s experience are more important than test scores. The use of test scores was seen as more appropriate in deciding which teachers to lay off, coming just behind principal evaluations as the most important factors to consider.

The public wants teachers from the ranks of top achievers. More than 75 percent of people polled said they think top high-school students should be recruited to become teachers. Nearly three-quarters of respondents also said they’d encourage their brightest friend to become a teacher. The desire for better teachers even outweighed the need for top scientists, according to the poll. A slightly higher percentage of people (48 percent) said top science and math students should become teachers versus those who said they should pursue a career in science (47 percent).

Technology is good, but learning should happen at school. Almost everyone polled said that having the Internet in schools is important (91 percent) and that access to computer technology in schools is important (95 percent). However, 59 percent are opposed to having high-school students take online classes at home. And—even more telling—half of respondents said it’d be better to have students taught in person by a less effective teacher than online by a more effective teacher.

Teachers’ unions get mixed reviews. Nearly half of those polled—47 percent—said they think teachers’ unions have hurt the quality of public schools. That’s up from the 38 percent who said so in 1976. Yet when it comes to the battles between teachers unions’ and state governors looking to reduce their influence, more than half (52 percent) said they side with the unions.

We like school choice—but vouchers not so much. Nearly three-quarters of those polled—74 percent—favor letting parents choose which schools their children attend. That’s up from 62 percent in 1991. However, 65 percent oppose letting parents send their children to private schools at taxpayer expense, up from 52 percent in 2002.

Obama Orders Revamp of ‘No Child Left Behind’

Education Secretary Arne Duncan announced Monday that President Obama would sign an executive order to allow schools who are falling short of No Child Left Behind to circumvent the law. PBS NewsHour’s Gwen Ifill discusses the policy shift with Justin Snider of The Hechinger Report.

Watch the full episode. See more PBS NewsHour.

Transcript:

GWEN IFILL: And to our second education story: about changes to the law known as No Child Left Behind.

Nearly a decade after it was enacted, a growing number of schools are having trouble meeting the law’s benchmarks. States had been required to achieve 100 percent proficiency in reading and math by 2014.

But, today, Education Secretary Arne Duncan said the president would sign an executive order to allow schools who are still falling short to circumvent the law.

SECRETARY OF EDUCATION ARNE DUNCAN: The law No Child Left Behind as it currently stands is four years overdue for being rewritten. It is far too punitive. It’s far too prescriptive, led to a dumbing-down of standards, led to a narrowing of the curriculum.

At a time when we have to get better, faster education than we ever have, we can’t afford to have the law of the land be one that has so many perverse incentives or disincentives to the kind of progress we want to see.

GWEN IFILL: For more, we are joined by Justin Snider. He’s a contributing editor at The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit news organization that focuses on education.

Welcome.

We heard Arne Duncan said today that we should be tight on goals, but loose on the means of achieving them. Why is an executive order needed to achieve these goals?

JUSTIN SNIDER, The Hechinger Report: Well, I would say it’s because we have tried the other way around. And we have tried to be tight on how to do it. And it hasn’t worked.

We have been under NCLB for nine years now, and the progress that everybody wanted to see, everybody expected to see — well, actually, realists probably realized we’re not going to — we’re not going to see it — hasn’t happened.

And so we have got to try something different this time.

GWEN IFILL: And you’re referring — when you say the progress that people — realists wanted to see was for Congress to act. And you say that is not going to happen.

So, explain to me what exactly this waiver would mean. Who gets it? Who decides who gets it? Exactly what do you have to do to get a waiver?

JUSTIN SNIDER: Well, Duncan has made it clear that all 50 states are eligible to apply for a waiver.

Unlike in Race to the Top, where it was clear from the beginning only some states would actually succeed, all 50 could succeed. But it is an application process. So a state will apply, and there will be an outside — not just the Department of Education — committee judging the state’s application and deciding whether to issue the waiver.

Whether it’s issued or not will depend on: one, whether the state has adopted standards that make it look like students will graduate from high school college- and career-ready; and, two, whether states are doing anything to evaluate their teachers’ effectiveness; and, three, whether they’re trying to turn around failing schools; and, four, whether they’re doing anything — or whether they have any plans to implement new accountability provisions.

Instead of the top-down way that is currently in place, they need to come up with local — local methods to enforce accountability.

GWEN IFILL: Let’s talk about accountability.

We just heard John Tulenko’s report that talked about the — the cheating scandal in the Atlanta schools, and how people, some people there, feel that that was because of the pressure to teach to the test, and that you had to raise test scores in order to keep your job.

Is — did the administration cite that or those — those incidents at all as a reason for trying to move on this now?

JUSTIN SNIDER: Well, I think Obama and Duncan and other people have been saying over and over again that what we have in Atlanta and elsewhere is a case of a few bad apples.

But I think, more and more, there’s reason to question that. We have seen similar scandals in Philadelphia, in D.C., and elsewhere that have been noted. And it’s interesting who is discovering those scandals. In many cases, it’s journalists.

And, in Atlanta, it was a very, very deep investigation, unlike in Washington, D.C. So, the closer you look, it appears the more widespread cheating is. But that’s not something that we’re hearing from the top.

GWEN IFILL: Arne Duncan said today that there was a universal clamor for this — for something to be done, even if Congress didn’t act.

Is that so? Is there — or is every state in the union saying, I want to do something about this now, or are there people who are fairly happy with the way the situation is now?

JUSTIN SNIDER: I would say most states are, in fact, clamoring. And it’s because they realize 2014 is no longer far away.

Of course, when NCLB was first passed under Bush in 2002, it was easy to think, well, who really cares? It’s 12 years away and we don’t have to worry about that now.

And, in fact, when states were allowed to set the goals year by year, how — how many — what percentage of proficiency they will have every given year, they basically pushed off into the distant future when they would get anywhere near 100 percent proficiency.

Now we’re in 2011 — 2014 is not far away anymore. And so the realization is, yes, that’s a completely unrealistic goal, and we need to do something about that, or else what we will have is, we won’t have high standards.

GWEN IFILL: But the goal…

JUSTIN SNIDER: And there’s been…

GWEN IFILL: The goal — pardon me — was to increase high standards and to increase accountability. Secretary Duncan said today that there would still be accountability.

How do you know that, if you’re basically letting people off the hook with these waivers?

JUSTIN SNIDER: Well, one thing that the waiver will require states to do is to have high standards and to have assessments that measure whether students are actually meeting those standards.

So, for instance, last year, there was an attempt — and a successful attempt — to introduce something called the Common Core Standards. And over 40 states and Washington, D.C., have now adopted them. And they’re thought to be a lot higher than most states have previously had.

So take a state like Tennessee. In the past, when Tennessee was defining its own standards and saying what percentage of their students were proficient, they were reporting back in mathematics that 91 percent of their students were proficient. Well, you introduce higher standards, and, suddenly, that percentage drops to 34 percent.

And so it really makes you think, well, these students aren’t really any different. It’s the same students. They’re just — and they’re performing the same. It’s just how you’re defining proficiency.

And so we see, once you raise the bar, proficiency levels drop. And, therefore, the state superintendents of instruction are all very concerned about this.

GWEN IFILL: Justin Snider of The Hechinger Report, thank you so much.

JUSTIN SNIDER: Thank you.

Ensuring quality in digital learning

Given the rapid growth in digital learning, how can we ensure that these new approaches to teaching and learning are of high quality?

Given the rapid growth in digital learning, how can we ensure that these new approaches to teaching and learning are of high quality?

Rick Hess of the American Enterprise Institute tackles that question in a paper released today by the Thomas B. Fordham Institute. He envisions a complex future for digital learning, where schools pull in lessons from numerous providers, each of which might cover just a small part of the overall curriculum. In some cases, schools could even allow parents to choose among multiple providers, Hess writes in “Quality Control in K-12 Digital Learning: Three (Imperfect) Approaches.”

With such potential variety, how can we ensure that all providers are good? It won’t be easy, Hess says, but there are three main tools we can use:

–Regulation: Digital-education providers can be required to prove that their instructors have certain credentials or that the online courses they offer are truly rigorous. To avoid “charlatans,” Hess says, providers could also be required to undergo financial audits.

–Accountability: This area presents some of the greatest challenges. State assessments aren’t going to be useful here because they aren’t fine-grained enough, Hess says. “What’s needed,” he writes, “is something more granular and more reflective of the unbundled vision of virtual schooling.” Students should be assessed frequently on targeted topics to prove they are mastering the material and to show how much they have learned from a specific digital-learning provider. This won’t be easy, as these kinds of tests aren’t common now.

–Market-based controls: Allowing parents to choose among providers will help weed out bad providers. The key here, Hess says, will be to have metrics by which parents can compare providers, including things like ratings and evaluations by experts—and even possibly crowd-sourced reviews of the providers, à la Amazon or eBay.

Each of the tools won’t by itself be enough, so we need to create a blend of all three to ensure quality, Hess says.

“A formidable task? Surely; because it is one that will ultimately determine whether the advent of digital learning revolutionizes American education or becomes just another layer of slate strapped to the roof of the nineteenth-century schoolhouse,” Hess writes.

Read the full report—the first in a series of six, to be released in the coming months—here.

Student teaching criticized in new study; schools of education fire back

Knowing the subject matter is all well and good, but one skill that many new teachers lack as they embark on their first year of teaching is how to control a classroom, or so say many critics of teacher education. This critical skill along with the other practical aspects of teaching — how to teach a new concept to a room of students with varying levels of ability, and then make sure they all understood, for example — aren’t typically figured out until teachers try out the book-learning they do in their courses in an actual classroom. For most teachers, this first attempt is during their student teaching.

A new study by the National Council on Teacher Quality out this week finds fault with the way many schools of education run their student teaching programs, however. Among other issues, the NCTQ criticizes a common set up in many teacher training programs where schools, not the colleges, get to pick which mentor teachers will get student teachers assigned to them. (The NCTQ would prefer that schools of education pick the teacher mentors.) It also points out that often these mentors aren’t required to be highly qualified or good at mentoring.

“While we certainly identified some exemplary institutions, this review suggests that all too often, too many elements of student teaching are left to chance,” the report said.

Schools of education have criticized the NCTQ’s assessment, however, saying the data they used to examine the schools was flawed or incomplete. Here’s Sharon P. Robinson, president of the American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education, responding in a New York Times article.

“A school can lose points for not having absolute control over the selection of the cooperation teacher,” Robinson said. “But we think these clinical experiences should be crafted in partnership with the schools, not dictated by either the principal or the education school.”

For more reaction to the report, also see this article in Inside Higher Ed.