Tuition soars as Obama cuts student-loan payments

President Barack Obama’s announcement this week that he will reduce student-loan payments comes as Americans are approaching one trillion dollars in student-loan debt and the number of people defaulting on their college loans is steadily rising. The College Board reported yesterday that higher-education costs, including for public universities, are at an all-time high.

But while the “Pay as You Earn” plan will make payments more manageable in the short term, graduates will end up paying more in the long run as interest accrues over a longer period of time, said a U.S. Department of Education spokesperson.

The president’s proposal, which amends the Income-Based Repayment initiative that President George W. Bush signed into law in 2007, allows for even lower monthly payments for up to six million graduates.

Obama and U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan said they are also making efforts to provide more transparent information to families before they borrow money for college. The Department of Education created a website that shows the schools charging the highest tuition and those with the fastest-growing tuition.

Unlike the American Jobs Act, a bill that would allocate $60 billion for refurbishing schools and paying teacher salaries, “Pay as You Earn” is an executive order that doesn’t require Congressional approval.

States move quickly to change teacher evaluations: 33 and counting

How fast are states moving to change their teacher evaluation policies in the wake of a major, years-long reform push by the Obama administration and others?

Very fast, according to a report released today by the National Council on Teacher Quality (NCTQ).

The NCTQ, an advocacy group that applauds most of these changes, counted 33 states that have tweaked–if not overhauled–their teacher evaluation policies since 2009, when the Obama administration’s education reform grant competition, Race to the Top, was announced. The changes have ranged from new laws that permit a teacher to be fired based on student test scores to requirements that teachers be evaluated at least once a year. The NCTQ found that 24 states now include test scores in teacher evaluations, and 18 have evaluations “significantly” informed by student achievement.

Race to the Top prize money has driven some states to revamp classroom observations of teachers and design systems to rate teachers using student achievement data. But others are rewriting their policies in the absence of such financial incentives.

“I don’t think we’re going to get to 50 too quickly,” report author Sandi Jacobs said yesterday in a conference call with reporters hosted by the Education Writers Association. “But I do think we’re going to continue to see these numbers go up.”

While more states, including some Race to the Top winners, have promised to make changes to how teachers are rated, the report doesn’t count those that have yet to pass statewide laws or take other concrete actions.

Yesterday, The Hechinger Report published a story in collaboration with the American Prospect looking at how these changes are translating into millions of dollars in contracts for private companies and nonprofits.

But how will these new policies change what happens in classrooms? Will they lead to improved student achievement?

The response on the conference call yesterday was, essentially, we don’t know yet. Jane Hannaway, a vice president of the American Institutes for Research (which has won contracts to design value-added teacher evaluation systems in Florida and New York, and which is among the supporters of The Hechinger Report) said she is confident that the new systems will be better than what they’re replacing.

“The huge variation in teachers is something that’s just indisputable right now,” she said. “A big leap has been made.”

And they’re off … States apply for the Early Learning Race to the Top competition

For some hopefuls, a successful application may involve building an early education system nearly from scratch. Mississippi, one of the 35 state contenders (Washington, D.C. and Puerto Rico also applied), offers no state-funded preschool or prekindergarten programs. The state has made some small steps toward creating more childcare options by funding an effort to support existing childcare centers and to open more of them, according to the National Institute for Early Education Research. Mississippi also has a quality rating system for its childcare centers, but participation is voluntary. But the state still has a long way to go to meet the Obama administration’s goals for the competition.

The applications will be judged on more than just whether they promise to create more preschool slots for low-income children, which is a requirement to win. The U.S. Department of Education will be looking for a common, statewide quality rating system, a statewide kindergarten-entry test (which will look at whether children are “ready” to start school), and efforts to connect the early years with the early elementary grades, among many other things.

Other states are already getting a jump-start. Connecticut is setting up a new state early learning agency, while New York announced that by 2014, all children will have to take a new test at the start of kindergarten.

There were several holdouts from the competition, however — and not all of them laggards in the area of early learning. Alyson Klein at Education Week writes that Idaho “applied in the earlier round of Race to the Top, [but] chose not to pursue the early-learning money after officials there raised concerns about creating a new program with one-time money.”

Early education advocates are welcoming the attention and money going toward their cause. One of the outcomes of the earlier Race to the Top competition, which focused on K-12, was that some of the losing states made major changes to their education systems anyway.

Here’s a short roundup of reactions and articles:

“California is eligible for the largest grant because of the number of low-income children in the state,” reports the Los Angeles Times.

Florida applied, but the governor said the state would back out if winning is linked to “new burdensome regulations … placed on private providers,” according to the Orlando Sentinel.

Minnesota would spend most of the $45 million it’s hoping to win on expanding access to preschool for low-income children, using the rest on professional development and accountability, the Pioneer Press reports.

Early Ed Watch at the New America Foundation has predicted the top contenders will be Colorado, Iowa, Maryland, New Mexico, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania and Vermont.

Studies point to principal training as ‘cost-effective’ reform

Often in reform efforts focused on teacher effectiveness, principals are overlooked. Two new studies examining the National Institute for School Leadership, a for-profit company that works in 19 states, point to the importance of school leaders. Researchers found statistically significant gains on test scores at hundreds of schools in Pennsylvania and Massachusetts with principals trained by the institute.

These are not the first studies to reach the conclusion that leadership matters. A 2009 study done by New Leaders for New Schools found that principal effectiveness accounted for 25 percent of student gains. Teacher effectiveness, by comparison, accounted for 33 percent. And school reformers–both in traditional public schools and charters–have been clamoring for better leadership development for years.

These new studies, conducted by Old Dominion and Johns Hopkins Universities, provide a new argument for the training programs: They can be cost-effective.

The National Institute for School Leadership (NISL) charges districts or states $15,750 to prepare in-district trainers, who then train aspiring principals and veteran school leaders, with the institute’s support. Fees for a principal to undergo the training range from $2,500 to $5,250, depending on the number of participants in the 12- to 15-month program.

In Pennsylvania–where schools with NISL-trained principals beat their peers by almost 10 percentage points on state tests–the average cost per principal was $4,000, or $117 per student.

The company is buying new advertisements “to bring home that point,” said President and CEO Bob Hughes. “You can get … effects for very little money by concentrating on the leadership.”

In the Massachusetts study, students in 38 schools that had a principal who went through the leadership training program in 2007 and remained at the school through 2010 saw gains that were “quite large” compared to other school-reform efforts. On average, students gained the equivalent of an extra month of learning.

“Out of all the professional development funding that is spent, only about 1 percent relates to the principal or the leadership of the school,” Hughes said. “Almost all of it is focused on the teaching … but we need to widen that.”

The researchers concluded in the Massachusetts study that it may be more practical to train principals at struggling schools instead of removing them, a main strategy under Obama administration-led reforms.

The federal government’s School Improvement Grants, aimed at the bottom 5 percent of schools nationwide, come with four possible plans a failing school can adopt, but all require that the principal be fired if he or she has been in the position for more than two years. The requirement has led some schools across the country to turn the money down.

But even for those schools that took the money and fired their principal, Hughes sees his group as having an important role in working with their replacements. “We believe that just the sheer numbers mean that most of the [hires] will be coming from the” same district, he said. “And those are the ones we really want to focus on.”

New report: Dropout rates five times higher for poor students

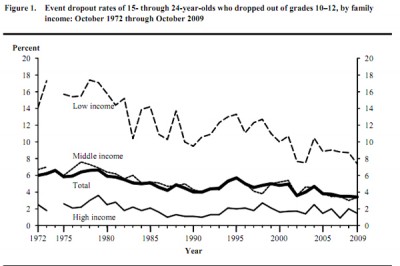

Sen. Tom Harkin’s ( D-Iowa) new proposal to reform No Child Left Behind is the latest attempt by policy makers to fix the country’s “dropout factories,” identified in the bill as schools with lower than a 60-percent graduation rate. But a new report has found a silver lining amid the crisis: The number of dropouts is already on the decline.

A new National Center for Education Statistics report on dropout rates has found that while there has been an overall decline in dropouts since 1972, there are still 3 million students between the ages of 16 and 24 without a high school diploma, a disproportionate number of whom are minority and poor.

The report also measured the “status dropout rate,” which shows the percentage of school-age youth who are not in school and who haven’t earned a diploma or alternative credential, with largely the same results. Under this measure, the difference between Hispanic and white young people was even greater. While 5.2 percent of white youth were not in school, that number was 9.3 percent for black youth and 17.6 percent for Hispanic youth.

Mixed reactions to the new NCLB bill

Senators Tom Harkin (D-Iowa) and Michael Enzi (R-Wyoming) announced new legislation to revamp the 2001 No Child Left Behind law yesterday, garnering some strong reactions from the education policy world. The senators said the 865-page bill would provide more support to “dropout factories,” which they defined as schools with a graduation rate of less than 60 percent, and would scrap a central NCLB measurement called Adequate Yearly Progress (AYP), replacing it with a promise from states to make “continuous improvement.” Some are praising the bill for putting more control back into the hands of states, while others believe it lacks clear goals. Some reactions:

RiShawn Biddle, who writes the conservative blog Dropout Nation, warned against lowering accountability and said the new bill was contrary to traditional Republican views on education.

“Stepping back accountability at the federal level — especially when congressional leaders are unwilling to force states to adopt Common Core standards in reading and mathematics — means setting back reforms, especially the very school choice measures Republicans and conservatives proclaim they support,” Biddle wrote. “But these days, when it comes to No Child, the plans being offered for its re-authorization merely declare that helping all children succeed in school and life is not in anyone’s thoughts.”

The national teachers unions, The American Federation of Teachers and the National Education Association, both came out in support of the new legislation. The AFT released a statement saying it recognizes the need for higher standards and more robust teacher evaluation systems.

The AFT: “The Harkin-Enzi proposal attempts to address a broken accountability system and acknowledges the importance of adopting higher standards, including the Common Core State Standards.”

Education Sector, a think tank, praised the elimination of the “unattainable target like 100% proficiency by 2014” under AYP, but was disappointed that there is “no new accountability yardstick in place.” It also offered an initial analysis of other elements of the bill here.

Bob Wise, president of The Alliance for Quality Education, thought that the bill was a step in the right direction, especially in how it will deal with “dropout factories.”

“The legislation unveiled today by Senators Harkin and Enzi is especially important for the nation’s high schools. For too long, high schools have been overlooked by federal education policy. This proposal would concentrate improvement efforts on high schools with graduation rates below 60 percent, often referred to as ‘dropout factories.’ It would establish a common, accurate calculation of graduation rates, helping to ensure that the nation’s high schools are held accountable for preparing students for college and careers. It would also support comprehensive efforts by states to strengthen the literacy skills of all students, including young people in high school.”

Six organizations, The Education Trust, Children’s Defense Fund, The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, The National Council of La Raza, The Center for American Progress Action Fund and The National Center for Learning Disabilities sent a joint letter to Senator Harkin expressing their concerns that the bill’s achievement goals are vague and could harm special-needs students.

“The loss of goals and progress targets would dismantle the positive aspects of NCLB’s accountability system and be a significant step backward that we can ill afford to take,” the letter said. “Your proposal contains much that could help low-income students, students with disabilities, students of color and English-language learners. But without goals and progress targets it is all but impossible to ensure that these good intentions will actually add up to better outcomes for students.”

Grover Whitehurst, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, told the New York Times:

“Harkin’s bill would return control to the state departments of education and the local school districts, and they’re the ones that got us into the mess that No Child was designed to fix,” Whitehurst said. “Districts and states have not been effective in delivering quality education to children from low socioeconomic backgrounds, so why should we think they’ll be effective this time around?”

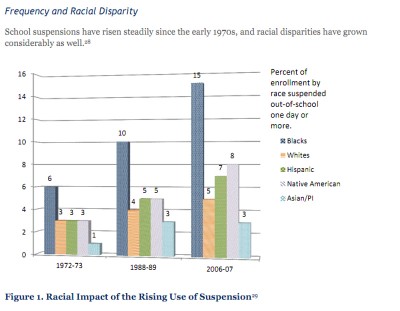

School discipline records show racial disparities

A report released today argues racial disparities in suspension and expulsion rates are hurting academics for minority students.

The report, by the National Education Policy Center at the University of Colorado Boulder, combines information gathered from a variety of recently released studies. It shows that black male middle school students are nearly three times more likely than their white counterparts to be suspended. Suspension rates for black female middle-schoolers are four times higher than those for their white peers.

Data obtained in North Carolina, for example, showed schools suspended first-time offenders who were black far more often for committing the same minor offenses as white students.

Aside from greater suspension rates, the study shows that black students are suspended more often for behavior that is seen as subjective, such as being disrespectful, making excessive noise or exhibiting threatening behavior, while white students are punished for more objective transgressions like smoking, vandalism, or using obscene language.

Out-of-school suspensions, which are also more common with first-offender black students, can not only be disruptive to the student’s progress in school, but also add hardship to a student’s family, the report’s author, Daniel Losen, argued.

The report discourages excluding kids who misbehave, calling it “unwise and unproductive,” and suggested some solutions moving forward:

— that schools be more transparent with their suspension data, which Losen argued should be reported by race, gender and disability status.

— that the reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act include positive incentives for schools, districts and states that reduce their suspension rates.

— that the federal and state government count out-of-school suspensions in measuring a school’s effectiveness.

Should we revive academic tracking?

A new report showing that some high-achieving students fall behind (although not far behind) as they progress through school is reviving an argument in favor of tracking students by ability levels.

America’s focus on closing the achievement gap during the past decade has left “advanced students to fend for themselves,” Frederick Hess, a researcher at the American Enterprise Institute, argues in a blog post on the New York Times website. (Disclosure: Hess sits on the advisory board of The Hechinger Report.)

“If we want to do right by our highest-achieving students—and maintain America’s international competitiveness—we should rethink the move to eradicate tracking,” writes Michael Petrilli, executive vice president of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, a conservative think tank that advocates for school choice and charter schools.

But critics of tracking have long argued that, on the ground, it has been very harmful to minority children, who have often been funneled into less challenging classes that don’t prepare them for college or careers.

Are we facing a crisis for high-achieving students? Is tracking the way to go to fix it? What do history and research tell us?

First, here is a synopsis and some thoughts on the report that is prompting the revival of the tracking debate, published by the Fordham Institute.

The Fordham report finds that a large number—though not a majority—of students who rank highly on tests in earlier grades lose ground in later grades (but not much ground: most stay at or above the 70th percentile). They are replaced by a larger number of so-called “late bloomers,” meaning that American schools are, overall, increasing the numbers of high-achievers by the end of high school. The report also finds that high-achieving students in high-poverty schools make the same amount of progress as high-achieving students in low-poverty schools. And, finally, low- and middle-achievers—groups that include a disproportionate number of minority and poor students—are catching up to their high-achieving peers.

This seems like mainly good news, but the report finds some nuggets of gloom.

Past research hasn’t found that the gains of low-performers come at the expense of high-performers, the report notes, although it has found that lower-performers generally make gains faster than high-performers. The Fordham report bolsters this finding: high-achievers didn’t show growth as quickly as middle- and low-achievers among the two groups of students studied. This finding suggests that American schools are making progress in closing the achievement gap, since 90 percent of the high-achievers in the sample are white, even though white students only make up 75 percent of the sample overall.

The authors also find this stunted growth among high-achievers “distressing,” however. The Fordham researchers hypothesize that the discrepancy in growth between the two groups is the result of schools’ focus on lower-achieving students. They suggest that No Child Left Behind’s elevation of standardized testing has forced schools to obsess over “bubble students”—the kids who are on the cusp of proficiency—to the detriment of others.

This analysis would probably get a “Hear, hear!” from many teachers and principals. But they might also talk about the difficulty of pushing high-achievers even higher. Helping a third-grader who still struggles to read fluently master the mechanics of reading is a different task than helping a third-grader who has already mastered reading understand a more difficult text, pushing the student from Charlotte’s Web, say, to The Adventures of Tom Sawyer. The study addresses this issue briefly, in a footnote, noting that the test the authors use doesn’t have an achievement ceiling, but also that “at some point, reading development becomes subject dependent, and tests of general reading may not adequately measure it.”

One bright spot, according to the report’s authors, is the finding that poverty doesn’t matter when it comes to progress for high-achievers. But it does matter when it comes to achievement levels: In their study, higher poverty rates generally predicted lower overall academic performance. That is, high-achievers at high-poverty schools were in lower percentile ranks than their high-achieving peers at more affluent schools. So students in poor schools may progress at the same rate as students in wealthier schools, but they are still behind.

What does all of this mean? Petrilli says the findings should urge us to resume the practice of sorting students into different academic tracks by ability level, to ensure that high-achieving students don’t suffer from dumbed-down instruction. In further support of this argument, Hess points to a RAND Corporation study, which found that high-achieving students do worse if they’re in general-education classes.

Even if some high-achieving students lose ground because they are being slowed down by lower-achieving peers, critics of tracking argue that there’s good reason to be cautious about reviving the practice. C. Kent McGuire, president of the Southern Education Foundation, doesn’t dispute that high-achieving students might do better in an accelerated environment, responding to Petrilli and Hess’s arguments on the Times blog. McGuire warns, however, that tracking has a problematic history. (He also wonders whether tracking has really been eliminated from most schools, as Petrilli argues.)

Here is a (very) brief outline of tracking’s history:

The concept was born at the beginning of the last century, as immigrant children flooded the public-school system. The practice of separating children by ability picked up pace in the 1970s, just as school desegregation was getting under way in many cities.

In theory, tracking would help the smartest students reach even greater heights. In reality, tracking did not always funnel the most intelligent children into challenging classrooms. Often, a designation of “gifted and talented,” or “advanced,” or “honors” was simply a proxy for social class, race or ethnicity.

A case in point is what happened in Louisville, Ky., the subject of a book I’m writing about the history of desegregation. Louisville introduced the Advance Program, an accelerated track for children who did well on an intelligence test and were recommended by their teachers, just after the courts forced the school district to begin busing. Perhaps this was a coincidence, but data show that even as the schools became integrated, the new tracking system kept blacks and whites mostly separate inside school walls.

In the 1990s, Louisville’s gifted and talented program was only 11 percent black, while the school system was 30 percent black. Black children were much less likely to take the test to get into the Advance Program track. Even when they did, and even if they scored above the cutoff for admission, they were less likely to be recommended for the program than their white peers. White students, on the other hand, were more likely to make it in even if they scored below the cutoff.

This was a trend that played out nationally in schools with tracking. (For a deeper look at the history of tracking, see this study, by researchers at the Education and the Public Interest Center in Boulder, Colo.) New York City has had a particularly fraught battle over ensuring that the gifted and talented label isn’t disproportionately assigned to white students.

The Fordham researchers argue that high-achieving students have been ignored as concerns about the achievement gap between minority and whites have escalated, and emphasize that the country’s economic and political future depends on how we nurture top-flight students. Their critics worry that reviving a system that has traditionally favored a select few will hurt everyone.

Duncan announces ambitious federal plan to boost teacher preparation

U.S. Secretary Arne Duncan speaking at NBC's Education Nation earlier this week. (Photo by Nick Pandolfo)

The Obama administration thinks states aren’t being aggressive enough in tracking how teachers are prepared and making education schools accountable for results. Education Secretary Arne Duncan laid out an ambitious three-part plan this morning that the administration hopes will radically change how states measure the effectiveness of their teacher preparation programs, provide additional scholarship money for teachers in training and fund programs that aim to diversify the teaching workforce.

“Our shared goal is that every teacher should receive the high-quality preparation support they need so that every student can have the effective teacher they deserve,” Duncan said. “But unfortunately, we all know that the quality of teacher preparation programs today is very, very uneven. The current system that prepares our nation’s teachers offers no guarantees of quality for anyone.”

Duncan said the plan, called “Our Future, Our Teachers,” was inspired by research finding that nearly two-thirds of new teachers feel unprepared for the classroom and that only 15 percent of teachers in high poverty schools come from the top third of college graduates.

The administration wants measurement of a teacher training program’s effectiveness to move more toward outcome-based data like student performance on standardized tests, job placement and teacher retention rates. Duncan also said the plan would encourage states to ask education schools to get feedback on their programs from graduates and their principals.

Louisiana and Tennessee, both of which have state-wide data systems that track academic growth of a teacher’s students by the preparation program they attended, were called out as potential models for the rest of the country.

“It’s the outcomes that matter,” Duncan said at Education Sector, a non-partisan think tank that hosted a panel discussion where Duncan made the announcement. “For decades teacher preparation programs have had virtually no feedback loop to identify where their programs prepare well for the classroom and where they need to improve.”

Under this new plan, the Department of Education will assist states in developing more comprehensive data systems, reward good programs and help them scale up, but also help states reshape or close low performing programs.

Labeling a teacher training program ineffective is something that rarely happens. In 2010, Duncan noted that only 37 of more than 1,500 teacher preparation programs across America were deemed low performing, with more than half of states claiming to have no poor programs.

Our Future, Our Teachers was widely welcomed as a huge step in the right direction by groups with different agendas. Dennis Van Roekel, president of National Education Association, the nation’s largest teachers union, called it “a good day.” This sentiment was echoed by Wendy Kopp, CEO and founder of Teach For America, an alternative certification program for teachers, and heads of education schools and national organizations like The National Center for Teacher Quality.

“It’s a nice change of tone,” Van Roekel said. “To talk about building up the profession instead of tearing it down.”

The new plan will give high achieving students up to $10,000 in the last year of their teacher preparation program.

The final element of the plan is a $40 million dollar proposal that would support teacher training programs in minority-serving institutions. It will fund Augustus Hawkins Centers of Excellence across the country with up to $2 million to diversify a teaching workforce that has become whiter and more female in recent years.

Federal government to grant money to successful charters

In a vote of confidence for charter schools it deems “high quality,” the U.S. Department of Education announced grants totaling $25 million to charter school networks they believe have proved successful at raising student achievement.

“Several high-quality charter schools across the country are making an amazing difference in our children’s lives, especially when charters in inner-city communities are performing as well, if not better, than their counterparts in much wealthier suburbs,” U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan said in a press release on Wednesday. “Every one of our grantees serves a student population that is majority low-income and virtually all exceed the average academic performance for all students in their state.”

Charter schools are publicly funded but typically freed from rules and regulations that traditional public schools must adhere to. The new grant will give the largest share — nearly $10 million — to help build the KIPP network another 16 schools throughout the U.S.

In New York City, the Success Charter Network, run by Eva Moskowitz, will receive almost $2 million to construct six new schools in New York. The network runs nine schools in the city.

Moskowitz and KIPP co-founder David Levin sat down earlier this month with PBS Education Correspondent John Merrow, who writes the blog Taking Note, to discuss the charter movement’s influence on American education. Levin had just been featured in a New York Times article by Paul Tough.

Charter schools first opened in Minnesota in 1992, and now represent about five percent of all schools in the U.S.

They are only responsible for educating about two percent of students, yet they’ve been embraced in major American cities like New Orleans and Detroit.

Some have questioned the need for charters at a time when public schools face diminishing resources and renewed pressure to perform. In addition, charters must often compete with public schools for space and students.

Moskowitz argued for schools to become “more compelling places” where kids actually want to go.

Moskowitz and Levin agreed on most points during their talk with Merrow, but differed on the benefits of rote learning. Both felt teaching should be considered a far more important job than it is.

“[Teachers] are trapped in a system that doesn’t nurture success,” Levin said. “The biggest tragedy in public school right now is that you can be a great teacher and it is completely uncertain what happens to your kids the next year.”

Below is a chart showing all the grantees that will receive federal dollars to expand their charter school networks.

| Name | Funding Amount | Project Description | |

|---|---|---|---|

| KIPP Foundation in consortium with KIPP regions | $9,463,103.00 | 18 new schools in Atlanta, GA, Austin, TX, Chicago, IL, Washington, DC, Gaston, NC, Houston, TX, Jacksonville, FL, Los Angeles, CA, Memphis, TN, Newark, NJ, New York, NY, and San Antonio, TX | |

| Rocketship Education | $1,881,569.00 | 56 new schools in Oakland, Milwaukee, New Orleans, and Chicago | |

| DC Preparatory Academy | $878,824.00 | 4 new schools in Washington, DC | |

| Success Charter Network, Inc. | $1,740,970.00 | Project description: 6 new schools in New York | |

| Richard Milburn Academy, Inc. | $1,575,562.00 | 6 new schools in Texas | |

| Uncommon Schools | $1,400,000.00 | 9 new schools in Newark and Boston | |

| Breakthrough Charter Schools | $3,488,060.00 | 8 new schools and 3 expanded schools in Cleveland, OH | |

| Alliance College Ready Public Schools | $3,139,983.00 | 10 new schools in Los Angeles | |

| Cosmos Foundation, Inc. | $1,431,929.00 | 7 new schools in Texas |

Source: ed.gov