Will cheating scandals change the focus on high-stakes testing?

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution has another explosive story out this week about possible cheating on standardized tests. This time, the newspaper looked at suspicious circumstances in nearly 70,000 schools across the country and found “red flags” in about 200 districts, an analysis that “suggests a broad betrayal of schoolchildren across the nation,” the newspaper said.

The newspaper looked for schools where test-scores had abnormally large leaps or drops from year to year. In Atlanta, an earlier investigation led the district to put more than 100 educators on paid administrative leave, and it is currently moving to fire some of them. (Four have already resigned rather than go through with a hearing.) This latest series of reports may lead to a similar fallout in other states and districts. More interesting to watch, however, will be whether the AJC investigation and another one published last year by USA Today in partnership with The Hechinger Report will have an impact on state and federal education policy.

The newspaper looked for schools where test-scores had abnormally large leaps or drops from year to year. In Atlanta, an earlier investigation led the district to put more than 100 educators on paid administrative leave, and it is currently moving to fire some of them. (Four have already resigned rather than go through with a hearing.) This latest series of reports may lead to a similar fallout in other states and districts. More interesting to watch, however, will be whether the AJC investigation and another one published last year by USA Today in partnership with The Hechinger Report will have an impact on state and federal education policy.

The investigations into cheating have added fuel to the debate over standardized testing, which has become a big part of how states rate, reward and sanction schools and, increasingly, individual teachers and principals. The Obama administration has called for a move away from an over-reliance on standardized testing and the “teaching to the test” that critics say is an inevitable result. Yet the federal government is, at the same time, putting pressure on states to rate teachers based on student growth—often measured using tests—through several different programs, including the Race to the Top competition and the School Improvement Grant program, which have funneled billions of federal dollars to states and districts. In some cases, the accountability push has driven states to create even more high-stakes tests.

Is an obsession with accountability based on standardized tests causing the rash of cheating? Or is the cheating evidence that the public education system is rife with bad apples who need to be identified and removed from the classroom—a task the new accountability systems are meant to aid in? Are there any reliable, comparable and affordable alternatives for measuring schools’ performance—something many educators and policymakers agree is important—other than standardized tests?

In the short term, the cheating scandals—which appear now to be more widespread than some thought—may lead to a shakeup in district staff. In the long term, we’ll be watching to see if they lead to a shakeup in policy.

Little teacher support for some Obama school-reform strategies

Teachers are skeptical about several of the major reform ideas the Obama administration and education activists are pushing to turn around the nation’s struggling schools, a new survey commissioned by Scholastic and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation has found. (Disclosure: the Gates Foundation is among the many funders of The Hechinger Report.)

Fewer than a third of teachers believe reforms like longer school days or years and merit pay for teachers will improve student achievement, the survey found. Under half of those surveyed believe common assessments across all states will help. Common standards also ranked low on the list of reforms that teachers see as important.

All of these strategies have been key requirements in two major reform pushes by the federal government, the Race to the Top competition and the School Improvement Grant program. The federal government has invested billions of dollars in these reform efforts.

All of these strategies have been key requirements in two major reform pushes by the federal government, the Race to the Top competition and the School Improvement Grant program. The federal government has invested billions of dollars in these reform efforts.

The strategy supported by the greatest number of teachers is increasing “family involvement and support.” Eighty-four percent of teachers say that would have a “very strong impact”—and 14 percent say it’d have a “strong impact”—on student achievement. High expectations, effective and engaged principals and fewer students in each class are other strategies supported by a large majority of teachers.

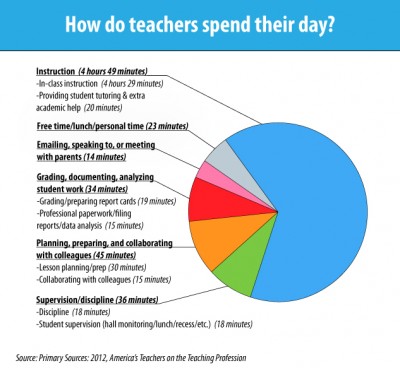

More than 10,000 public-school teachers, from pre-k to 12th grade, completed the online survey last summer. Respondents received a Scholastic gift certificate in exchange for participating, and the results were weighted to be nationally representative of the U.S. teaching force. Teachers reported, on average, a workday of 10 hours and 40 minutes. Roughly two-thirds of that time is spent at school during required hours, while the other third—or more than three hours daily—consists of working at home or at school after-hours.

The survey results overlap with the findings of another teacher survey published recently, the MetLife Survey of the American Teacher. In both surveys, teachers reported that more of their students are dealing with hunger and homelessness. Both surveys also found that fewer than half of teachers are “highly” or “very” satisfied with their jobs.

Despite apparent skepticism around some of the Obama administration’s reform strategies, teachers appear to approve of the recent national focus on overhauling teacher evaluations, albeit with some caveats. Eighty-five percent of teachers questioned in the Scholastic/Gates survey support the use of student academic growth to evaluate their job performance. Nevertheless, only a quarter of teachers believe standardized tests are “an accurate reflection of student achievement,” suggesting that teachers are unlikely to support the complicated statistical models that many states are adopting to measure teacher performance based on student standardized test-results.

In addition, teachers seem wary of another increasingly popular strategy for evaluating teachers: principal observations. Although teachers appear to welcome more frequent principal observations—95 percent say these should happen annually—fewer than a third think that principal observations should count for a lot in their evaluations.

Teachers instead seem to want more varied and intense evaluations than reformers are calling for. They would like to have more self-assessments, peer reviews and evaluations by their department chairs. The survey results also show widespread support of teacher tenure, which has come under attack from politicians in some states. Still, the survey suggests that many teachers might accept changes to how tenure is currently granted: Nearly 90 percent say tenure “should reflect evaluations of teacher effectiveness,” and even more say “that tenure should not protect ineffective teachers.”

As India expands higher education, questions remain about quality and competition

A classroom at the Nalanda Open University in Patna on a testing day at the end of a semester. (Photo by Sarah Garland)

Will India’s higher-education system catch up to those of world leaders, and should its economic rivals be concerned? American RadioWorks aired a podcast today that addresses these and other questions about India’s education ambitions. I discussed India’s higher education building boom with host Stephen Smith, and how the country’s open universities fit into plans to expand access as the country faces a booming population of young people.

Click here to listen to the interview.

Affirmative action on the docket again: Justice Kennedy’s past opinions hint at outcome

Affirmative action in college admissions is on the Supreme Court docket again this year after a white student named Abigail Fisher challenged a University of Texas program meant to promote diversity on UT campuses.

Affirmative-action proponents, including many university leaders, are concerned that if the University of Texas loses, efforts to increase diversity in U.S. colleges will be severely undercut. Critics of affirmative action are thrilled that the issue is back in play after a 2003 Supreme Court decision in a lawsuit against the University of Michigan seemed to settle the issue, allowing colleges and universities leeway to consider a student’s race as one of many factors in admissions decisions.

Minority enrollment in higher education has been on the rise, according to a 2010 Pew Research Center study, with Hispanic enrollment increasing the fastest. Whites made up 62 percent of the freshman class at four-year institutions in 2008, the report found, down from 83 percent in 1976. (That’s about the same as the percentage of whites in the larger population, although the percentage of minorities among young people is higher.) Nevertheless, the percentages of black and Hispanic young people enrolled in higher education are still lower than those of whites and Asians.

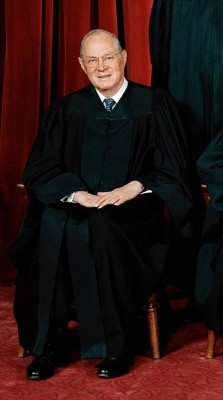

Which way the Supreme Court goes on this case will most likely rest with Justice Anthony Kennedy, the swing vote on the court, who has been a vociferous critic of racial quotas, but who has also published some fairly nuanced opinions on race in college admissions. Because Justice Elena Kagan has recused herself from the case, there will only be eight justices voting.

If Kennedy votes with the conservative wing of the court, the Texas program could be overturned, meaning many colleges and universities—both public and private—may have to overhaul how they make admissions decisions. If he joins the three remaining liberals, resulting in a tie, the lower-court decision—which upheld the Texas program—would stand. Or, he could come down somewhere in the middle, joining the conservatives or liberals, but writing a separate opinion that will hold more weight due to his swing-vote status.

That’s what happened in the last case involving race and schools in 2007, and lawyers for both sides will no doubt be poring over Kennedy’s past opinions as they plan oral arguments meant to sway him. Here’s a quick summary of what they will find:

In a 1992 decision in a desegregation case out of Georgia, Freeman v. Pitts, Kennedy had the following to say about whether K-12 schools should strive for racial balance in student populations:

“In one sense of the term,” he wrote, “vestiges of past segregation by state decree do remain in our society and in our schools. Past wrongs to the black race, wrongs committed by the State and in its name, are a stubborn fact of history. And stubborn facts of history linger and persist.” But, “racial balance is not to be achieved for its own sake,” he concluded.

In the 2003 University of Michigan case, Grutter v. Bollinger, although he sided with the conservatives who wanted to strike down the school’s use of race in admissions, Kennedy wrote a separate opinion, distancing himself from their more hard-line views. A racial quota, he wrote, “can be the most divisive of all policies, containing within it the potential to destroy confidence in the Constitution and in the idea of equality.” Yet race might play a role as a “modest factor among many others.”

Finally, in his opinion in desegregation cases out of Louisville and Seattle in 2007, he came down in the middle on the question of whether the districts’ use of race to assign K-12 students was permissible under the U.S. Constitution.

“That the school districts consider these plans to be necessary should remind us that our highest aspirations are yet unfulfilled,” he wrote. “But the solutions mandated by these school districts must themselves be lawful. To make race matter now so that it might not matter later may entrench the very prejudices we seek to overcome.”

He added, however, that “diversity, depending on its meaning and definition, is a compelling educational goal a school district may pursue,” and criticized the opinion of Chief Justice John Roberts, saying it implied “an all-too-unyielding insistence that race cannot be a factor in instances when, in my view, it may be taken into account.”

At the University of Texas, officials insist—and the lower courts have agreed—that race was just one factor among many that were used to admit a small pool of students (under 10 percent). We’ll see if their program is one of the instances of schools using race in admissions that Kennedy deems permissible.

This post also appeared on the College Inc. blog of The Washington Post on February 23, 2012. Reproduction of this story is not allowed.

Is the era of teaching to the test nearing an end?

One more state received a waiver from the federal No Child Left Behind Act requirements this week, and the debate about what the waivers will mean for education policy continues.

Jon Stewart interviews U.S. Education Secretary Arne Duncan on Thursday about the Obama administration's education reform agenda.

New Mexico, which was left waiting for a verdict on its application after an announcement that 10 other states had been granted waivers last week, got word Wednesday that its waiver had been approved. Among a long list of other things that reviewers of the application wanted changed, the state had to provide more detail about how it planned to meet the student performance benchmarks that are still a requirement under the more flexible waiver rules.

How will the waivers impact education nationally? I discussed the issue this week with Jane Williams, host of Bloomberg EDU, in a show that also included commentary from U.S. Education Secretary Arne Duncan, Senator Michael Bennet (D-Colo.), and reporter John Hechinger of Bloomberg News. The show covers questions about whether disadvantaged populations like special-education students and English language learners will fall through the cracks, and how the waivers might impact the reauthorization of No Child Left Behind.

Another concern that has come up in the wake of the waiver announcements is whether pressure to “teach to the test”—which most experts and educators agree No Child Left Behind has intensified—will continue. The waivers are meant to encourage states to move beyond standardized tests in English and math, which generally only cover grades three through eight, to come up with multiple measures to hold schools and, increasingly, individual teachers accountable for their performance. Duncan repeated this week his belief that the waivers will alleviate, not exacerbate, the teaching-to-the-test phenomenon.

Some teachers seem skeptical. One teacher, writing on Twitter during a town hall meeting Duncan held this week, asked: “Why base so much of a teacher’s evaluation on a single test score?” referencing the growing number of states that are incorporating student test-scores into teacher evaluations in response to federal education policy, including the Race to the Top competition and the NCLB waiver process. And on Thursday, Daily Show host Jon Stewart grilled Duncan about the Obama administration’s reforms, asking at one point whether they wouldn’t just encourage a “lazy susan of tests” in a host of subjects, instead of just in math and reading.

For more on the waivers and what they’ll mean going forward, listen to “Bloomberg EDU,” which airs Friday evenings at 10 pm; Saturdays at 5 am, 11 am and 8 pm; and Sundays at 12 am and 7 pm. (All times listed are Eastern.)

Bloomberg Radio can be found on WBBR 1130 AM in the New York metro area, Sirius/XM Channel 113, and via live Webstream at http://www.bloomberg.com/radio/.

Obama’s new teacher plan: Not so new?

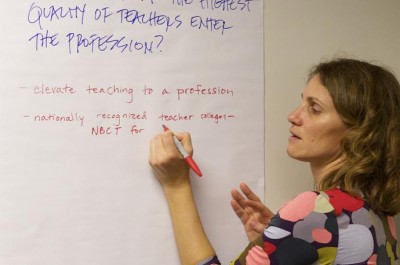

A National Board Certified Teacher shares ideas in Dec. 2011 with the Department of Education on strengthening the teaching profession. (Photo courtesy of the U.S. Department of Education)

U.S. Education Secretary Arne Duncan made his case yesterday for the $5 billion that he and President Barack Obama want Congress to put toward a new grant competition to overhaul the teaching profession. The program would follow the mold of the administration’s $4.35-billion Race to the Top competition in form and, it seems to a large degree, also in substance.

Alyson Klein at Education Week summed up the basics of the new plan: “They want to use the money to help states and districts do a whole host of things, including: overhaul teachers’ colleges to make them more selective, create career ladders for teachers, give extra money to teachers who work in tough environments, bolster professional development, revamp tenure, craft evaluation systems, and make teachers’ salaries more competitive with other professions.”

It’s unlikely that the Obama administration will get the money for the new program, given the bitter political climate in Washington, D.C. right now, but for many of the program’s goals, this may not matter too much.

The teaching profession is already undergoing sweeping changes nationally, in no small part because of the Obama administration. About half of states are on a path to change teacher evaluations to factor in both student test-scores and other measures of teacher performance. Some states adopted these new policies because they won Race to the Top, while others did so because they were hoping to win Race to the Top. And now a new crop of states is set to redo their evaluations as a condition of getting a waiver from No Child Left Behind requirements.

And then there are the struggling schools that won federal School Improvement Grants, most of which had to promise to create new evaluation systems to get the federal money under rules set by the Obama administration. It appears in many places that SIG schools are influencing their districts and even entire states to adopt new evaluation systems on a larger scale.

At the same time, several states are trying to make teacher tenure harder to attain and easier to lose, and some have already succeeded. Quite a few are seeking to increase accountability for education schools, using rating systems that could be linked to funding in an effort to improve teacher quality. Merit pay is spreading slowly but steadily to an increasing number of places across the nation. (The federal Teacher Incentive Fund has helped in this expansion.)

So what’s new about the program the Obama administration is proposing besides the additional money to further its reform agenda?

Duncan hosted a town hall meeting yesterday in D.C. to discuss the plan with teachers. For one, the project is meant to involve a close collaboration with teachers themselves on ways to “elevate the teaching profession,” Duncan said. The National Education Association, the nation’s largest teachers union, was on hand at the town hall, and has praised the plan so far. (Klein writes that the proposal to increase teacher salaries in particular has them “pretty jazzed.”)

During the town hall, one teacher mentioned bringing educators out of the isolation of their classrooms so they could work together. (I can’t recall a single school I have visited in the last two years that hasn’t transformed itself into a “professional learning community” in an effort to do just that, but that doesn’t necessarily have to do with an explicit push by the Department of Education.)

Duncan also brought up the large amount of federal spending on professional development—$2 billion a year—and how bad most of the offerings are. Although there have been some changes—one-day workshops, which are seen as mostly useless by experts in the field, are losing favor—this is still an area that has received little attention in recent years. States and districts have focused on identifying good and bad teachers, but less has been done policy-wise to encourage better ways to help all teachers improve.

Another big issue discussed was the need for a cultural shift, so that teachers are more valued by society at large. The name of the program gets at this goal; it’s called the RESPECT project. But how to increase respect for teachers is a more nebulous and difficult job.

The Obama administration seems to believe greater respect for the teaching profession will follow the reforms it has already set in motion, and which it clearly wants to expand even further and faster with this new block of money. It’ll be interesting to see if the teachers they want to become more active in this effort will agree with the administration’s approach.

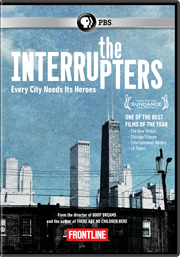

An American problem: Is changing culture enough to stop youth violence?

Halfway into The Interrupters, a documentary airing Tuesday night on PBS’s Frontline, Caprysha Anderson, an 18-year-old teenager from inner-city Chicago, rides a carousel for the first time. The seemingly mundane event is transformative for Caprysha and for the audience’s understanding of the depths of her violent upbringing.

She has just gotten out of jail. Her face is scarred from fighting. She looks old for her age. But wide-eyed as the carousel turns under the bright lights of a suburban mall, she seems briefly innocent and young.

She has just gotten out of jail. Her face is scarred from fighting. She looks old for her age. But wide-eyed as the carousel turns under the bright lights of a suburban mall, she seems briefly innocent and young.

A few moments later, she breaks down in tears.

The film, by Steve James, producer of Hoop Dreams, and Alex Kotlowitz, journalist and author of There Are No Children Here, is a year in the life of CeaseFire, an anti-violence program started in Chicago more than a decade ago. Filming began in 2009 during an especially violent time in the city, when more than 150 young people were murdered over eight months. The goal of CeaseFire is not to dismantle gangs or even really to turn young people away from lives of crime. It’s to tamp down the violence and save lives. The outreach workers of CeaseFire, all of them former gang members (and most with lengthy prison records), keep their ears open for rumors and make the rounds of Chicago’s worst neighborhoods in order to “interrupt” fights and shootings before they occur.

CeaseFire treats violence like a disease. A former World Health Organization doctor, Gary Slutkin, who spent years fighting infectious diseases in Africa, developed the concept. As Slutkin explains in the film, the outreach workers, or “interrupters,” are not there to cure the disease. They are there to stop its spread.

The method works. Violent crime in the neighborhoods where CeaseFire is in operation drops dramatically. But it seems impossible for the outreach workers in the film to stop at just interrupting the violence. Instead, they form deep and complicated relationships with the people they meet in the course of their work. Caprysha Anderson takes the carousel ride because Ameena Matthews, the daughter of a notorious gang leader and herself a former gang member, has taken Caprysha under her wing.

Ameena meets Caprysha at a fight between two groups of boys in a housing project. Caprysha is the only girl involved. Soon, Ameena is inviting her to her daughter’s birthday party at a skating rink, and calling her relentlessly to check up on her as Caprysha worries about her mother’s drug addiction and tries to resist joining in the violence around her. Ameena takes on the role of the caring, patient parent that Caprysha never had but desperately needs.

Just as it’s impossible for the CeaseFire outreach workers not to dig more deeply into the lives of the young people they find on the street, it’s also impossible while watching their efforts not to think about the deeper causes of so much anger. The camera pans over rows of boarded-up, foreclosed houses. Unemployed young black men mill around aimlessly. “Every day they’re asking for jobs,” a CeaseFire staff member says at one point.

Slutkin, the doctor, argues that cutting down on the violence creates a pathway for solving deeper structural issues—poverty, unemployment, poorly performing schools, racial segregation. It’s a necessary first step. Believing that the bigger problems must be solved first is a way of just giving up, he suggests. It’s similar to the argument that some education advocates, like U.S. Education Secretary Arne Duncan (who appears in the film), make about school reform.

Yes, poverty and other wider societal problems are the main causes of low achievement in school, but you have to start somewhere, and schools have long been the route up and out of poverty. Change the culture of low expectations, and then watch schools and whole communities achieve success. Change the culture of violence, and then watch as young people and whole communities stop the cycle of self-destruction.

In many ways this is an empowering message. During a teenage boy’s funeral, Ameena stands at a pulpit and tells the mourners, most of them also teenagers, “We’ve got a responsibility to bring up our community be vibrant.” Individuals need to start thinking differently and acting differently, and then things will be different. It’s similar to the argument of Charles Murray in his new book, Coming Apart, in which he links the problems of the white working class to a culture of laziness and relaxed family values. Culture is the key to improving the lot of the disadvantaged, he says. A 2010 New York Times article reported that increasingly, other scholars are also re-embracing the idea that “a culture of poverty” is one reason the problems of the poor persist.

But The Interrupters complicates this argument. The filmmakers cut between Slutkin and an interview with Eddie Bocanegra, a CeaseFire worker who spent years in prison for killing a man during a shootout when he was 17. “It’s just a Band-Aid,” he says of the work that he and his fellow interrupters do. And by the end of the film, as we watch Caprysha Anderson struggling to turn her life around, the question comes to mind: After the interruption, what next? Is the interrupters’ hard work sustainable without a deeper effort to transform the conditions that led to the violence in the first place?

Ten states let off the No Child Left Behind hook

U.S. President Barack Obama announced today that he is letting 10 states off the hook for meeting requirements in the federal No Child Left Behind Act. The law, passed in 2001 with bipartisan support under President George W. Bush, called for all students to reach proficiency in English and math by 2014, a goal that educators and others have said is both impossible to reach and deeply flawed.

Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Indiana, Kentucky, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Jersey, Oklahoma and Tennessee all applied for waivers. (The hyperlinks go to waiver applications, courtesy of the Center on Education Policy.) New Mexico applied but was denied, though the Obama administration says it is working with the state to improve its application.

In an interview this morning on NPR’s “Here and Now” show in Boston, I spoke with host Robin Young about what Obama has asked of states in exchange for the waivers. In brief, the states agreed to adopt more rigorous academic standards (all of the states except for Minnesota have already formally adopted the Common Core State Standards for both English and math, which are new sets of standards pegged to college readiness).

They were also supposed to revamp accountability systems to focus on individual student progress, and to overhaul teacher and principal development and evaluation. No Child Left Behind, in contrast, rated schools based on whether students met certain benchmarks on state tests. The focus on proficiency, critics said, led schools to concentrate on so-called “bubble students,” those whose performance was near the proficiency cutoff, to the exclusion of the highest- and lowest-performing students.

While most people in the education world think No Child Left Behind is problematic, the waivers have not been universally embraced.

The Obama administration says the waivers reduce federal influence on state education policy, something conservative critics have complained about in the wake of the administration’s various reform initiatives, including the Race to the Top competition. “Rather than dictating educational decisions from Washington, we want state and local educators to decide how best to meet the individual needs of students,” Education Secretary Arne Duncan said in a press release today.

When the administration announced last August that it would grant waivers, some civil rights advocates expressed concern that the waivers might lessen pressure to renew NCLB (which is long overdue for re-authorization) and reduce the attention on minorities and other disadvantaged groups. They have been reassured by the waiver requirements, however.

But others see the waivers as more federal meddling on par with the Race to the Top competition, and argue that the Department of Education is once again attaching federal money to guidelines that align with Obama’s education-reform ideas.

In a related development, Education Week reported today that the chairman of the House Education and the Workforce committee, John Kline (R-Minn.), introduced a pair of bills to replace NCLB. The bills have rather different priorities than the waivers; as reporter Alyson Klein put it, “the federal role in K-12 education would be almost entirely eviscerated.”

Nearly 30 more states are expected to apply for NCLB waivers in a new round that will start this month.

We’ll continue to update this post with more coverage and links throughout the day.

UPDATE: The president just spoke about the waivers at the White House, and reiterated Duncan’s argument that the waivers will reduce federal influence on state education policy. He said the waivers would alleviate pressure on schools to “teach to the test” and on states to lower standards. “We’ve combined greater freedom with greater accountability,” he said. “Each of these states has set higher benchmarks.”

Here is more coverage from around the web:

Education Week with reactions.

USA Today on the politics.

The Christian Science Monitor on how NCLB has lost its “bite.”

MinnPost.com on the “end run” around Congress.

Are school choice and integration the secret ingredients to lowering crime?

Young African-American men at risk of committing crimes were much less likely to do so when they attended higher-performing schools outside their neighborhoods, according to a study published today in Education Next.

The study, by David Deming, a professor of education and economics at Harvard, looked at students in Charlotte-Mecklenburg, the North Carolina school district where the concept of busing as a remedy to school segregation was born.

In 2001, the school district dismantled its desegregation plan, but kept in place a plan that gave preference to low-income students seeking to enroll in higher-income schools or other schools outside their neighborhoods. Deming compared students who were selected in a lottery to leave their neighborhood with those who weren’t selected (as space constraints limited students’ choices).

The study is interesting for a couple of reasons. For one, it didn’t focus on test-scores as a measure of student outcomes. Achievement on tests is often the default in studies like this one, but educators and others often criticize the heavy reliance on standardized scores because the tests are narrow and often flawed or easily gamed. As Deming puts it in his report: “Programs can yield long-term benefits without raising test scores, and test-score gains are no guarantee that impacts will persist over time.”

Instead, Deming used criminal behavior as the primary measure of how well students turned out. He tracked whether students who were at particularly high risk of committing crimes—meaning they had low test-scores, lived in high-crime neighborhoods, and had other characteristics associated with criminal behavior—actually did so. Those who enrolled in their school of choice were much less likely to get into trouble than those who weren’t given the opportunity to do so.

The second interesting issue raised by the study is what’s at play in producing those outcomes. The author attributes the results to the fact that students were able to choose (something school-choice advocates like to hear).

But I wonder whether it was instead the fact that they were able to attend more economically integrated schools, as the point of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg plan was to promote voluntary desegregation. Plenty of research suggests that disadvantaged students perform much better in racially integrated schools.

I asked Deming if it was school choice per se that improved student outcomes, or the fact that students attended more integrated schools. Here’s how he responded:

“This is a hard question to answer with certainty. The mechanism for crime reduction could be better educational opportunities, economic integration, or a change in their exposure to negative peer influences. Probably it is a combination of all of these things.

“One thing I will say is that the choice schools were fairly similar in terms of race and free-lunch status (an indicator of poverty) to the students’ neighborhood schools, although the choice schools had higher-achieving students in them. In other words, students chose schools where their peers were similar demographically but better academically. In that sense, I would say that integration was probably not the main mechanism, although it may have played a role.”

So, choice appears to have mattered, but so might have the demographic composition of the schools the students attended. Perhaps this study suggests a point where two sides of the education debate can find common ground?

Bankruptcy attorneys warn that student loans could be the next crisis

A group of bankruptcy attorneys who predicted the mortgage fiasco that helped cause the current economic downturn said today that rising student debt could fuel another crisis just as big.

Nearly half the members of the National Association of Consumer Bankruptcy Attorneys (NACBA) said in a survey conducted last month that the number of their potential clients with student-loan debt has increased significantly in the last four years.

The association said average debt for college seniors who graduate with student loans rose 5 percent in 2010—the last year for which the figure is available—to $25,250. The amount of student borrowing annually has crossed the $100 billion threshold, and total student debt now exceeds $1 trillion.

“This could very well be the next debt bomb for the U.S. economy,” said NACBA president William E. Brewer, Jr.

The amount of debt taken out by parents to pay for college for their children has grown 75 percent since 2005, the association said. An estimated 17 percent of parents whose children graduated in 2010 took out loans, up from 5.6 percent a decade earlier. Parents who took out college loans owe an average of $34,000, which will compound to $50,000 over a standard 10-year repayment period.

“Parents who take out loans for children or co-sign loans will find those loans more difficult to pay as they stop working and their incomes decline,” threatening their assets and retirements, said John Rao, attorney for the National Consumer Law Center and NACBA’s vice president.

More than two-thirds of the 860 bankruptcy attorneys surveyed also said that student-loan providers are becoming more aggressive in collecting debts.