Halfway into The Interrupters, a documentary airing Tuesday night on PBS’s Frontline, Caprysha Anderson, an 18-year-old teenager from inner-city Chicago, rides a carousel for the first time. The seemingly mundane event is transformative for Caprysha and for the audience’s understanding of the depths of her violent upbringing.

She has just gotten out of jail. Her face is scarred from fighting. She looks old for her age. But wide-eyed as the carousel turns under the bright lights of a suburban mall, she seems briefly innocent and young.

She has just gotten out of jail. Her face is scarred from fighting. She looks old for her age. But wide-eyed as the carousel turns under the bright lights of a suburban mall, she seems briefly innocent and young.

A few moments later, she breaks down in tears.

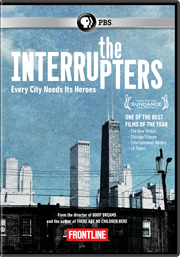

The film, by Steve James, producer of Hoop Dreams, and Alex Kotlowitz, journalist and author of There Are No Children Here, is a year in the life of CeaseFire, an anti-violence program started in Chicago more than a decade ago. Filming began in 2009 during an especially violent time in the city, when more than 150 young people were murdered over eight months. The goal of CeaseFire is not to dismantle gangs or even really to turn young people away from lives of crime. It’s to tamp down the violence and save lives. The outreach workers of CeaseFire, all of them former gang members (and most with lengthy prison records), keep their ears open for rumors and make the rounds of Chicago’s worst neighborhoods in order to “interrupt” fights and shootings before they occur.

CeaseFire treats violence like a disease. A former World Health Organization doctor, Gary Slutkin, who spent years fighting infectious diseases in Africa, developed the concept. As Slutkin explains in the film, the outreach workers, or “interrupters,” are not there to cure the disease. They are there to stop its spread.

The method works. Violent crime in the neighborhoods where CeaseFire is in operation drops dramatically. But it seems impossible for the outreach workers in the film to stop at just interrupting the violence. Instead, they form deep and complicated relationships with the people they meet in the course of their work. Caprysha Anderson takes the carousel ride because Ameena Matthews, the daughter of a notorious gang leader and herself a former gang member, has taken Caprysha under her wing.

Ameena meets Caprysha at a fight between two groups of boys in a housing project. Caprysha is the only girl involved. Soon, Ameena is inviting her to her daughter’s birthday party at a skating rink, and calling her relentlessly to check up on her as Caprysha worries about her mother’s drug addiction and tries to resist joining in the violence around her. Ameena takes on the role of the caring, patient parent that Caprysha never had but desperately needs.

Just as it’s impossible for the CeaseFire outreach workers not to dig more deeply into the lives of the young people they find on the street, it’s also impossible while watching their efforts not to think about the deeper causes of so much anger. The camera pans over rows of boarded-up, foreclosed houses. Unemployed young black men mill around aimlessly. “Every day they’re asking for jobs,” a CeaseFire staff member says at one point.

Slutkin, the doctor, argues that cutting down on the violence creates a pathway for solving deeper structural issues—poverty, unemployment, poorly performing schools, racial segregation. It’s a necessary first step. Believing that the bigger problems must be solved first is a way of just giving up, he suggests. It’s similar to the argument that some education advocates, like U.S. Education Secretary Arne Duncan (who appears in the film), make about school reform.

Yes, poverty and other wider societal problems are the main causes of low achievement in school, but you have to start somewhere, and schools have long been the route up and out of poverty. Change the culture of low expectations, and then watch schools and whole communities achieve success. Change the culture of violence, and then watch as young people and whole communities stop the cycle of self-destruction.

In many ways this is an empowering message. During a teenage boy’s funeral, Ameena stands at a pulpit and tells the mourners, most of them also teenagers, “We’ve got a responsibility to bring up our community be vibrant.” Individuals need to start thinking differently and acting differently, and then things will be different. It’s similar to the argument of Charles Murray in his new book, Coming Apart, in which he links the problems of the white working class to a culture of laziness and relaxed family values. Culture is the key to improving the lot of the disadvantaged, he says. A 2010 New York Times article reported that increasingly, other scholars are also re-embracing the idea that “a culture of poverty” is one reason the problems of the poor persist.

But The Interrupters complicates this argument. The filmmakers cut between Slutkin and an interview with Eddie Bocanegra, a CeaseFire worker who spent years in prison for killing a man during a shootout when he was 17. “It’s just a Band-Aid,” he says of the work that he and his fellow interrupters do. And by the end of the film, as we watch Caprysha Anderson struggling to turn her life around, the question comes to mind: After the interruption, what next? Is the interrupters’ hard work sustainable without a deeper effort to transform the conditions that led to the violence in the first place?