From the convention: American Federation for Children and the push for school choice

Republicans in Tampa did more Tuesday than tally the state roll call. The party also voted on its official platform for the rest of the campaign season. In education, the GOP platform spells out its support for school choice, “whether through charter schools, open enrollment requests, college lab schools, virtual schools, career and technical education programs, vouchers or tax credits.”

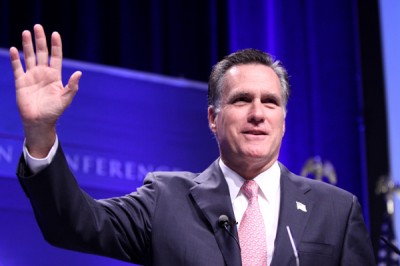

It’s similar to what Mitt Romney has described in his education white paper, in which he calls for low-income and special-education students to be able to attend any school.

The inclusion was a victory for the American Federation for Children, a national group that advocates the expansion of school choice. At the convention, The Hechinger Report talked with Randan Swindler, the federation’s director of external affairs, to learn more.

Q: What do you think about what Mitt Romney has proposed around school choice?

A: We’ve actually been working with the platform committee to finalize getting school choice on the platform – on the Republican platform. We’re very supportive of Governor Romney’s position on school choice. He’s kind of an all-in kind of guy. He supports parental choice through charter schools, through vouchers, through tax credits, scholarships. And we would just really encourage him to expand on that in his presidency if he were elected.

What do you think of what President Obama has done over the past four years?

He’s definitely expressed some support for giving parents choices. It was a little bit disappointing that he didn’t reinvest in the D.C. Opportunity Scholarship Program. We had to fight for that but it has been reauthorized, which was something that we supported. But we would definitely like to see him use stronger language to support parental choice and back away from the unions and find ways that he’s actually supporting parents as opposed to playing the union line.

The Hechinger Report recently did a story about Louisiana’s voucher program and one issue raised was that many schools teaching questionable things might be eligible for vouchers. What do you say to that?

It’s up to the parents. As a parent, it’s a personal responsibility, looking at the curriculum. It’s just another option for parents, so we’re not going to get involved in saying what schools can and cannot teach. We want them to be accountable and transparent for the parents so that they have the options that they need to make the best decisions for their kids.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

From the convention: What would happen to education under Obama or Romney administrations?

The Obama campaign has recently begun highlighting the differences between his education agenda and that of Mitt Romney. Will these new talking points be a theme at the Republican and Democratic nominating conventions? The Hechinger Report will be on the ground in Tampa and Charlotte to find out.

President Barack Obama delivers remarks on higher education and the economy at the University of Texas in Austin, Texas August 9, 2010. (Official White House Photo by Pete Souza)

Up until last week, education was rarely addressed on the campaign trail. But the stakes for the future of the U.S. education system are high in this election: The Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA), which funds and delineates the federal government’s role in the nation’s schools, will most likely be reauthorized in the next four years.

The last revision of the bill, President George W. Bush’s No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB), has been heavily criticized for its reliance on standardized tests and seemingly unattainable standard of universal proficiency by 2014. President Obama would ease up on some of the law’s restrictions, but maintain a robust federal role in local schools. Romney would move to reduce the government’s investment and involvement in education.

President Obama and Romney do share some common ground in their education platforms; both support charter schools, for example, and merit pay for the country’s best teachers. They both also speak of our failing schools and the pressing need to prepare American students for global competition. But the paths they would take to do this differ in important ways.

The Obama administration has largely used a carrot-and-stick approach to changing the education system. Over the past six months, the Department of Education has granted waivers from NCLB penalties to 26 states in return for promises that they will introduce other education reforms and accountability measures.

Under Obama’s Race to the Top initiative, a competition in which states promised a series of changes to their education systems in return for federal money, an unprecedented number of states are overhauling how teachers are evaluated, paid and let go.

Some Republicans have criticized Obama’s education initiatives as overreaching by the federal government. Although Romney would not eliminate the Department of Education – as President Ronald Reagan once sought to do – he would consolidate the agency with another or “perhaps make it a heck of a lot smaller,” he told donors in April.

Under a Romney administration, school choice would be a priority. The Obama administration has thrown its support behind charter schools – awarding some points in Race to the Top for states that raise caps on the number of charters. Romney, though, wants to see a school choice system that includes vouchers for private schools in addition to more charters. Romney’s white paper on education calls for low-income and special-needs students to be able to go to any school, public or private, of their choice, using funds from the federal government.

Romney’s support of private sector involvement in education extends into higher education. He wants to allow private bank involvement in student loans (Obama eliminated their role in March of 2010). He has also praised for-profit, private colleges and campaigned on their campuses. Romney argues that for-profit schools increase competition in the post-secondary landscape and can help keep the cost of college down.

The Obama administration is one of many critics of for-profits, arguing that they leave graduates with large loans and few employment opportunities. Under Obama, the Department of Education developed regulations that will pull federal financial aid from schools where graduates are unable to find “gainful employment.” Romney would repeal this.

Due to Tropical Storm Isaac, the Republican National Committee Convention is off to a slow start; all speeches for the evening have been postponed until later in the week. Starting tomorrow, check in with The Hechinger Report this week and next for analysis of speeches, coverage of off-the-floor convention events and exclusive interviews with national education leaders.

Study: African American voucher students more likely to go to college

African-American school children in New York City who received a voucher to attend a private school were more likely to enroll in college than their public school counterparts, according to a study released last week by the Brookings Institution and Harvard’s Program on Education Policy and Governance.

For more than a decade the study tracked students who received privately-funded vouchers in the late 1990s. African-American students in that group were 24 percent more likely than those in a control group to attend college and 58 percent more likely to attend private four-year colleges. Hispanic students who received vouchers were also more likely to enroll in college, but only by a small, statistically insignificant, amount.

The study’s authors—Brookings’ Matthew M. Chingos and Harvard’s Paul E. Peterson, a voucher advocate—compared the college matriculation rates of about 1,300 students who received a voucher to a similarly-sized control group who did not win vouchers in a lottery. The study is unusual in that it focused on long-term educational attainment rather than short-term test-score trends.

Vouchers have resurged in popularity over the last two years, but it’s unclear whether the New York study has much relevance for states like Indiana, Wisconsin, and Louisiana, which have recently expanded or created voucher programs. The designs of those states’ programs, as well as the overall quality of their private-school sectors, vary significantly.

The study’s authors argued their research illustrates the promise of vouchers in a Wall Street Journal op-ed. But Rutgers professor Bruce D. Baker critiqued the study in a blog post, saying other factors—apart from vouchers—could have contributed to the higher college-going rates for African-Americans at the private schools.

More information and context about vouchers can be found in a recent Hechinger Report article.

Will a new conversation about funding pre-k take hold in Mississippi?

A new conversation about pre-k is emerging in Mississippi as citizens examine the reasons behind the state’s woeful academic performance—documented in the first story of our “Mississippi Learning” series and since taken up by other news media in the state.

This is an important conversation in Mississippi, which has the highest rate of childhood poverty in the United States and some of the lowest test scores. The Magnolia State remains the only state in the South that doesn’t fund pre-k.

This is an important conversation in Mississippi, which has the highest rate of childhood poverty in the United States and some of the lowest test scores. The Magnolia State remains the only state in the South that doesn’t fund pre-k.

A recent report on the ACT, used in college admissions, shows that Mississippi’s children not only start behind—they stay behind. Only 11 percent of the state’s students were ready for college-level work in English, math, reading and science—compared to a national average of 25 percent.

Mississippi’s littlest learners often start school at a disadvantage, our reporting has found. The Clarion Ledger recently published a series on the topic, showcasing an array of opinions. The paper also editorialized in favor of a state-funded pre-k program. Earlier this month, I participated in an American Public Media podcast on the topic.

Syndicated columnist Sid Salter weighed in as well, in a piece that has appeared in newspapers throughout the state.

“[T]he undeniable fact that Mississippi is trailing the nation and the region in early childhood education is at times just another brick in the public policy wall that impedes the state’s long term growth and development,” Salter wrote.

The lagging performance of Mississippi’s children makes it clear that ignoring opportunities to stimulate young minds before formal classroom education begins can have dire consequences. The human brain reaches 80 percent of its adult size by age 3 and a full 90 percent by age 5. And research shows that children who have had a high-quality preschool experience end up with larger vocabularies and higher achievement, along with more advanced social skills, than their peers who haven’t.

Entering kindergarten without certain skills is a recipe for continually staying behind. Yet Mississippi has so far been unable to make state funded pre-k a priority, Salter noted in his column, citing economic reasons.

“The biggest obstacle to state-funded pre-kindergarten in Mississippi is fiscal, not partisan,” he wrote. “Lawmakers have struggled to provide bare bones funding to the state’s existing K-12 public schools, universities and community colleges for decades.”

Where the pre-k conversation will go in the state remains uncertain. Much will depend on Republican Gov. Phil Bryant and the state legislature when they resume a discussion about education in January that is likely to focus on charter schools and reform. It’s possible, though, that pre-k could become part of the discussion, as it has countless times before. But will discussion lead to action?

America’s math problem: Should we get rid of algebra?

Is math holding the United States back?

Last week, a community-college student from Harlem, speaking at a meeting of educators and community activists, told a harrowing story about his battle to get a degree. Raised by a single mother in a neighborhood wracked by violence, he had struggled to make it through high school. Then his mother died of cancer, leaving him to raise his three younger siblings alone. He pressed on in school despite new emotional and financial burdens, but there was a remaining obstacle that sometimes seemed like it would overwhelm him: algebra.

Like thousands of would-be college graduates in the United States, he had been forced to enroll in remedial math classes in college, and the difficulty of passing it reduced his chances of reaching graduation. Half of community-college students take remedial classes, and only 10 percent of those who do graduate within three years, Business Week reported in May. And a fifth of four-year college students enroll in remediation, of whom only about a third graduate in six years.

Those statistics come from a report on remediation published in April by Complete College America. The report’s numbers suggest that math requirements may be the primary obstacle to graduation for many students: In many states, a larger percentage of students enroll in remedial math courses than in remedial English courses.

But experts and educators are divided on what to do about America’s math problem. Should we scrap algebra altogether, or try instead to better prepare students to understand it? The debate has been particularly heated this summer after a New York Times op-ed by Andrew Hacker asked the question, “Is Algebra Necessary?”

Hacker compiled a list of statistics supporting his argument that it isn’t: “Of all who embark on higher education, only 58 percent end up with bachelor’s degrees. The main impediment to graduation: freshman math. The City University of New York, where I have taught since 1971, found that 57 percent of its students didn’t pass its mandated algebra course. The depressing conclusion of a faculty report: ‘failing math at all levels affects retention more than any other academic factor.’ A national sample of transcripts found mathematics had twice as many F’s and D’s compared as other subjects.”

Hacker is not alone in advocating for the elimination of algebra, at least from the college curriculum. The Complete College America report suggests placing “students in the right math.”

More coverage

• The worst eighth-grade math teacher in New York City

• U.S. math education is broken

• Math education in the U.S. vs. abroad

“Most students are placed in algebra pathways when statistics or quantitative math would be most appropriate to prepare them for their chosen programs of study and careers,” the report’s authors argue.

In a report released today by the American Enterprise Institute, Jacob Vigdor calls for a different approach. Although he too is dismayed by American students’ performance in math, he argues that the problem is how algebra is taught, not that it is taught at all. He believes that for many students, an introduction to algebra comes much too soon—in eighth grade—meaning the material must be dumbed down so they can understand it. His evidence includes a program in North Carolina’s Charlotte-Mecklenburg school district aimed at increasing the number of eighth-graders taking algebra; students there who took algebra earlier scored much lower on an end-of-year exam than students who didn’t, he notes.

Pushing algebra down to lower grades also alienates students who are able to grasp the concepts more easily, leaving fewer to be interested in pursuing math, as evidenced by the decline in math majors, according to Vigdor.

“The root of America’s math problem is the conflation of two goals: improving the absolute performance of American students and closing gaps between high and low performers,” Vigdor writes. “Following the failure of a significant initiative to accomplish both goals simultaneously—the ‘new math’ movement of the mid-twentieth century—successive reforms have focused attention on bringing lower-performing students up to standards. In the process, the standards have been lowered, and the advancement of higher-performing students has been allowed to languish. Designers of the nation’s mathematics curriculum, in short, have fallen into an ‘achievement-gap trap,’ raising the relative performance of average students in part by permitting the absolute performance of the best students to decline.”

His solution is not necessarily to do away with algebra for the masses, however, but to do a better job of differentiating how it’s taught to students of various abilities and backgrounds. “American students are heterogeneous, and a rational strategy to improve math performance must begin with that premise,” he concludes.

Getting rid of across-the-board standards in algebra isn’t likely to happen any time soon, however. Schools across the country are gearing up this fall to introduce new common standards, which promise that “students who have completed 7th grade and mastered the content and skills through the 7th grade will be well-prepared for algebra in grade 8” (italics in the original).

Ed in the Election: New York group tries to tie Romney to anti-union group

A New York-based group released a report this week trying to tie Mitt Romney to StudentsFirstNY, an education organization known for opposing teachers unions and supporting Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s often controversial education policies.

StudentsFirstNY is a local offshoot of a national organization founded in 2010 by Michelle Rhee, former chancellor of the District of Columbia Public Schools. In New York, the organization has pledged to raise $50 million in the next five years to support Bloomberg’s education policies, such as eliminating seniority-based layoffs for teachers.

The report, published by New Yorkers for Greater Public Schools, charges that “Romney donors and Republican insiders” plan to “control NYC education.” According to the report, which is titled “studentsfirstROMNEY FIRST,” StudentsFirstNY board members and funders have given more than $2 million to Romney and super PACs affiliated with the candidate.

The report’s authors warn of school closures and personnel reductions, arguing that “StudentsFirst NY is using a plan developed by Bain & Company and advocating actions that will treat public schools the way Romney’s Bain Capital treated companies.” (Romney served as CEO of Bain Capital from 1984, when he co-founded it, until 2002; he also served as interim CEO of Bain & Company in 1991-92.)

StudentsFirst dismissed the validity of the report. “Virtually every line in this report contains charges that range from absurd to dishonest,” Glen Weiner, the deputy executive director of StudentsFirstNY, wrote in a statement, according to The New York Times. “Clearly, the teachers’ union is so desperate to suppress a serious conversation about improving teacher quality and expanding school options for kids that it has set up a front group to threaten elected officials and concoct conspiracy theories.”

The Times pointed out that the report is “somewhat selective,” noting that the StudentsFirstNY board also includes members who donate to Democrats.

Meanwhile, President Barack Obama spent some time on the campaign trail talking to teachers in Iowa. “The main thing I wanted to do is just say thank you. … I know how tough it is to be a teacher,” he said, according to Politico. “I know you guys get a lot of satisfaction. Obviously you guys don’t do this for the money.”

Obama also spoke about the long overdue re-authorization of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (known under President George W. Bush as the No Child Left Behind Act). Its re-authorization has been stalled since 2007. Obama said the new bill his administration has been crafting would “maintain the best spirit of No Child Left Behind.” While many educators and advocates have extensively criticized NCLB, the law has also been praised for its emphasis on measuring the achievement of many student subgroups.

“But we want greater flexibility,” Obama added.

More states requiring students to repeat a grade: Is it the right thing to do?

Thousands of third-graders may have a sense of déjà vu on the first day of school this year: The number of states that require third-graders to be held back if they can’t read increased to 13 in the last year.

Retention policies are controversial because the research is mixed for students who are held back, but a report published on August 16th by the Brookings Institution suggests that at least for younger children who struggle with reading, repeating a grade may be beneficial.

The report, which examined a decade-old retention policy in Florida, was authored by Martin West of the Harvard Graduate School of Education. He argues that “the decision to retain a student is typically made based on subtle considerations involving ability, maturity, and parental involvement that researchers are unable to incorporate into their analyses. As a result, the disappointing outcomes of retained students may well reflect the reasons they were held back in the first place rather than the consequences of being retained.”

West comes to the following conclusion:

“Retained students continue to perform markedly better than their promoted peers when tested at the same grade level and, assuming they are as likely to graduate high school, stand to benefit from an additional year of instruction.”

The spread of stricter retention policies is connected to a wider movement to ensure all children are reading proficiently by third grade. The idea is based on research showing that children who don’t reach that target are often left behind as their classes move from “learning to read” to “reading to learn.”

Retention is not the only, or even the main, instrument in the toolbox promoted by advocates in the reading-by-third-grade movement. Intensive interventions, including pulling struggling readers out of class for individual or small-group tutorials, have become increasingly popular in many schools around the country. More states are also enshrining efforts to identify struggling readers and provide them early interventions in the law, as Education Week has reported.

Even so, the use of retention, even as a last resort for students who aren’t reading well enough on time, is still fraught with problems, many experts say. A report on third-grade literacy policies by the Education Commission of the States (ECS), published in March 2012, outlined what can go wrong with strict retention policies:

“While some researchers have found that retained students ‘can significantly improve their grade-level skills during their repeated year,’ others have found that less than half of retained students meet promotion standards after attending summer school and repeating a grade. Some research points to other negative effects, including a greater likelihood of bullying and victim behavior, or dropping out of high school.”

That is, assuming that retained students are no less likely than their peers to graduate from high school—which Professor West does—is not necessarily a good idea, according to the research.

In addition, the ECS report noted that minority and low-income students make up a disproportionate share of the students who are held back. “This raises serious questions about equity and the potential for prejudicing teachers’ attitudes toward the academic capabilities of retained students. Given these disparities, some view grade retention as punishing disadvantaged students who also may not have received the same quality of instruction as their more advantaged peers,” the ECS report said.

Educators have also questioned policies in which a decision to hold a student back is based solely on test scores.

In New York City, where Mayor Michael Bloomberg touted his ending of “social promotion” in the 2003-04 school year, educators quietly ignored the policy change. In the years after social promotion was officially ended, the number of third-graders held back actually decreased significantly over time (from 3,601 in the first year to 480 in 2008-2009, according to the city’s statistics). This year, the mayor had a “change of heart” and ended the policy.

As one Florida superintendent, Doug Whittaker, put it to Education Week last March in a story about the spread of retention policies: “After 10 years, I don’t like it. I don’t think it’s good for kids … I don’t care how the adults frame it: The people making those decisions forget what it’s like to be 8 years old.”

Is state-sponsored pre-k the solution for Mississippi?

What would help the children of Mississippi, which has test scores that are consistently among the nation’s worst? The Hechinger Report and Time magazine have partnered to take a long look at the state’s performance and try to find some answers and solutions.

From Hechinger editor Liz Willen’s first piece in the ongoing series:

Although neighboring states have made great strides in early education, Mississippi remains the only state in the South—and just one of 11 in the country—that doesn’t fund any pre-k programs.

Failure to prepare children for school costs the state a lot of money. One of every 14 kindergarteners and one of every 15 first-graders in Mississippi repeated the school year in 2008, the most recent year for which statistics are available. From 1999 to 2008, the state spent $383 million on children who had to repeat kindergarten or first grade, according to the Southern Education Foundation.

Willen recently joined a panel of experts with strong views on the topic to discuss why the largely poor and rural state consistently lags behind in education, and what approaches might improve the future of Mississippi’s schoolchildren. Some believe that state-sponsored pre-k would be a great place to start, while others insist that the answer lies with families and churches.

The forum was broadcast on Jackson State University television.

Ed in the Election: Where does Paul Ryan stand on education issues?

Mitt Romney’s pick of Rep. Paul Ryan (R-Wis.) as his vice presidential candidate over the weekend offers new clues about what a Romney administration could mean for federal education policy. Although Ryan hasn’t made education a signature issue during his seven terms in Congress, he believes the federal government should cut back its involvement in education.

“Stagnant student achievement levels and exploding deficits have demonstrated that massive amounts of federal funding and top-town interventions are not the way to provide America’s students with a high-quality education,” says Ryan’s website. “It is imperative, then, that we allocate our limited financial resources effectively and efficiently.”

Ryan is perhaps best known for the federal budget he proposed in April 2011, which included deep cuts to the federal Head Start program. Given his views on the federal role in education, Ryan would probably also cut other programs. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan said the budget could have “disastrous consequences for America’s children,” telling Congress it would include cuts to Title 1 funding for schools that serve low-income children. Republicans countered that this was speculation on Duncan’s part, according to Education Week.

In contrast to his running mate, Ryan opposed a measure that prevented student-loan interest rates from doubling this summer, from 3.4 percent to 6.8 percent. Both Romney and Obama agreed that Congress needed to act to keep the interest rates from jumping. (Ryan did vote for a plan to extend the 3.4 percent interest rate for another year, however.) The move was paid for by cutting part of Obama’s Affordable Care Act.

Ryan has also repeatedly voted for or proposed limiting funding and eligibility for Pell grants, which go to low-income college students. In his proposed budget, for instance, the eligibility requirements for Pell grants would be tightened so fewer students would qualify for them. And the amount of each Pell grant would not keep pace with inflation under Ryan’s plan, according to The New Republic.

Vouchers, which would subsidize students who choose to attend private schools, are a centerpiece of Romney’s education platform. Ryan voted to extend a Washington, D.C., voucher program that the Obama administration attempted to cut. (It was allowed to expire in 2009 before being reauthorized in 2011.)

Romney’s choice for a running mate was immediately blasted by the country’s teachers unions. American Federation of Teachers President Randi Weingarten, who has already endorsed President Obama for re-election, released a statement calling a Romney-Ryan ticket “the most out-of-touch … in decades.”

“Rep. Ryan’s record speaks for itself,” Weingarten said. “He would reduce, not expand, real opportunities for all students to have access to high-quality public education.”

Some states resisting Obama administration ed-reform requirements

This week the Obama administration announced it had released a total of 33 states from some No Child Left Behind requirements with the approval of Nevada’s application for a waiver from the law. “While well intentioned, the law’s rigid, top-down prescriptions for reform have proved burdensome for many states,” a statement from the U.S. Department of Education said.

But some states seem to be feeling the same way about the Obama administration’s own prescriptions for reform.

Georgia is in a contentious battle with the feds over the money it won through the Race to the Top competition. The Department of Education has threatened to reduce the state’s award by $33 million after Georgia changed aspects of its teacher evaluation system following a pilot program. Republican Gov. Nathan Deal—who came into office after Georgia submitted its application for the grant—has said he refuses to “defend a system that we have been warned will not work,” and fears lawsuits if he proceeds under the plan the feds originally approved.

Hawaii is among a handful of other states that have also seen their grants jeopardized after missing deadlines and encountering other obstacles. In Illinois, federal officials are unhappy that the state is rolling out new teacher evaluations over the course of the next four years. That’s too slow, the feds have said, and they’re threatening to deny Illinois a waiver from NCLB requirements if they don’t speed up.

Illinois officials have balked at the pressure to move faster, however, saying that rushing risks getting it wrong. (Many low-performing schools in Illinois have to introduce the new evaluations this year.)

“It is really hard work to do well, and it is really high stakes, and we’ve got to be thoughtful,” Chris Koch, the Illinois school superintendent, told the Chicago Tribune last month. “We are not trying to dodge anything. … We’ve done a lot of hard work, and the feds should honor state sovereignty in this regard and let us work within the time frame we approved.”

Tennessee, which got its evaluation system up and running last school year, has faced criticism for moving too quickly, as has Louisiana, which is starting this year without having piloted some of the key components of its new system.

The Tennessee Department of Education released an evaluation of its own evaluation system this summer. Among its findings, which were largely positive, the report also said the following:

“District and school administrators spent considerable time in evaluation training demonstrating an understanding of the different levels of performance for observations, and all evaluators passed a test demonstrating this understanding. However, in implementation, observers systematically failed to identify the lowest performing teachers, leaving these teachers without access to meaningful professional development and leaving their students and parents without a reasonable expectation of improved instruction in the future.”

Pushing states to hurry up or to follow plans that experimentation shows may be faulty might attract criticism, but the Obama administration would probably also be attacked if it gave away federal money with no strings attached. (Although conservatives who think the federal government is overreaching would certainly be pleased.) So far, no state that’s applied for an NCLB waiver or won Race to the Top money has walked away.