School districts prepare for fiscal cliff cuts

School districts around the country are worrying over stalled negotiations to avert the “fiscal cliff” at the end of the month, which could result in the loss of more than 8 percent of their federal funding. Education advocates and lobbyists, including for the two national teachers unions, are clamoring for a deal – specifically one that leaves the federal education budget intact.

Talks continued on Monday, and both sides seemed closer to an agreement. President Obama proposed a new counter offer to House Republicans, while Politico reported that House Speaker John Boehner was developing a Plan B that would raise taxes for some Americans. If the two parties are unable to come to an agreement by Jan. 1, though, a series of cuts will be triggered that include significant reductions to education spending. (The cuts wouldn’t have a large impact on many school districts until the beginning of the 2013-2014 school year, however.)

The Hechinger Report reached out to districts around the country to find out what would happen to them if the cuts were to kick in. Here are some of their responses:

Pharr-San Juan-Alamo Independent School District, Texas (31,633 students, 88.96 percent of students economically disadvantaged):

Our budget process for the 2012-13 school year begins in January. No decisions have been made yet on how we would adjust if the federal cutbacks occur. We have been assured that we will not be impacted until Sept. 1, 2013. Definitely, we would experience major cutbacks in staff and services. Many teacher aide and teacher positions would be lost. Class size would increase. Tutoring and other supplemental services would be impacted. Services for special needs students would be impacted as well as other federal programs. We will begin formulating our plan in January. It will be a several month process to develop our budgetary response to the cut backs.

–Superintendent Daniel King

Flint Community Schools, Michigan (9,606 students, about 85 percent of students economically disadvantaged):

Flint Community Schools could lose about 8 percent of our federal grants, which total approximately $25 million annually. That would mean a loss of about $2 million. As a result, the district’s Office of State and Federal Grants has been instructed to budget accordingly, until the federal budget impasse is resolved. Program coordinators are to work as if their budgets were 8 percent smaller. There are no plans to cut any programs at this point.

-spokesperson Robert Campbell

Northshore School District, Washington (19,818 students, 17.6 percent of students economically disadvantaged):

Given Northshore’s demographics, we don’t rely as much on federal funding as many other districts. That said, our calculations are that sequestration would result in a loss of $500,000 in federal funding, with most of that impacting our Title and IDEA programs [which are federal programs for, respectively, low-income and special-needs students]. With respect to Title [dollars] this would mean reduced reading and math intervention services and reduced funding for professional development. Our Title I funding is a major source of our intervention dollars, primarily aimed at closing achievement gaps. As we work towards implementation of the Common Core Standards, the loss of staff [professional development] support will be a real challenge. As for IDEA, we are still legally required to provide the appropriate services to students with special needs. Consequently, our ability to reduce programs or services in that area are more restricted. The result could be losses/reductions in other areas to offset the IDEA funding losses.

– Superintendent Larry Francois

(Statements have been edited for length and clarity.)

When the safety of school is attacked

Schools are supposed to be sanctuaries. That refrain has been echoing around the country following Friday’s massacre at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Conn., where a gunman shot his way into the building and murdered 20 children and six adults before taking his own life.

“I live between the Sandy Hook Elementary School and the house of the shooter, Adam Lanza. I seriously thought I lived in the safest place in America,” Newtown resident Addie Sandler wrote in USA Today. Sandler added that her children had attended Sandy Hook Elementary when they were younger. “The elementary school was a place of learning and laughter.”

For Carolyn Mears, a professor of education at the University of Denver whose son is a Columbine survivor, the fact that the shooting took place at a school – an elementary school, at that – is an attack on our sense of innocence.

“Schools are symbolic to our country, to our society,” she said. “Schools are the future. Schools are a place of hope of betterment.”

Many students across the country may balk at going to their own schools as a result of Friday’s events, predicted Marie Gray, a psychologist that specializes in child and adolescent developmental psychology and traumatic stress.

“It’s almost like everything we teach them goes out the window because of this heinous act,” she said. “How do we emphasis safety to them and let them know they’re going to be safe when something like this happens?”

It’s important to regain that sense of safety now, though, said Robert Klitzman, a professor of clinical psychiatry at Columbia University, adding children should be told that they are free from harm now and this is a “freak event.”

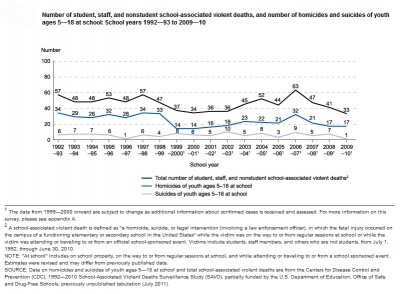

Although violence is rare, dozens of people are killed in schools each year. Other schools and their surrounding communities have been hit hard or destroyed by natural disasters.

After the shooting at Columbine, where 13 individuals were shot and killed and another 24 were injured, Mears set about learning what schools could do following such tragedies. In her book, Reclaiming School in the Aftermath of Trauma, she urges schools to think about the unthinkable and have plans in place, from what the chain of command will look like to how to teach children who have been traumatized.

Some students from Sandy Hook may suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder. They may regress, have reoccurring nightmares, or withdraw, experts said.

The entire community will need to work together to “build a new normal,” Mears said. Some students may never be able to step foot in the school again, but those who can return should do so when they are ready with parent and teacher support. “That can actually be very helpful,” she said, recalling her own experience.

Officials have not said if the school will reopen for classes; for now Sandy Hook students will be sent to a school in the nearby town of Monroe.

A pair of Newtown High School alumni have started a movement to knock down Sandy Hook and build a new school in a new location, underscoring the deep connection between students and their schools. “We cannot send the survivors to walk the halls of the school that were once covered in blood from their fallen classmates and faculty,” they wrote on Newtown’s Patch.com site. “Rebuilding Sandy Hook Elementary would give the survivors a new place to call home.”

But Gray suggested that doing so might reinforce victimhood and that returning to the scene may help some regain a sense of power. “The building is just a building,” she said. “The building didn’t do anything bad.”

Boards of trustees think the price of college is just about right

The boards of trustees and directors who oversee America’s colleges and universities think higher education has gotten too expensive—just not at their own institutions.

In a finding that suggests there’s little sense of urgency among governing boards to rein in the cost of college, more than half of 2,500 board members surveyed said higher education is too pricey. But nearly two-thirds contended that their own schools charge just about the right amount.

Nearly half said their institutions are already doing everything they can to stay affordable.

College costs have jumped 440 percent in the last 25 years, or three times the rate of inflation, outpacing even the spiraling cost of health care. Household income during that period rose only about 150 percent. At many universities, the increases have accelerated since the 2008 economic downturn.

Yet there is “a major gap” between how board members view the problem and how the public sees it, says Susan Whealler Johnston, chief operating officer of the Association of Governing Boards of Universities and Colleges, or AGB, which conducted the survey.

The disconnect comes at a time when governing boards appear to be asserting greater authority over the university administrations they oversee.

The board of visitors at the University of Virginia, for example, ignited a firestorm this year when it tried to remove the president for not moving fast enough in some areas. And while the decision was reversed, it was the latest battle between university administrators and boards of directors and trustees, who have also clashed in Iowa, Louisiana, North Carolina, Oregon, Texas and elsewhere.

The governing panels of private universities are elected by alumni or self-perpetuating, while those of public institutions are generally appointed by governors and legislatures.

Half are businesspeople, 25 percent are professionals and 16 percent are working or retired educators, according to a separate survey that the AGB released last year.

Nearly a third receive no financial training, and more than a quarter admit that they do not undertake much budgetary or financial oversight, the earlier survey found.

A nation reacts to horrific school shooting in Connecticut

Americans are again mourning and grappling with the question, ‘Why?’ after a gunman shot and killed multiple children at an elementary school in Connecticut on Friday. Twenty-eight were killed–20 of them children–at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Conn., according to law enforcement officials.

It will likely rank as the nation’s second deadliest shooting at a school, following the Virginia Tech massacre in 2007, in which 32 people were killed. In 1999, two students killed 13 people and themselves at Columbine High School in Colorado, an incident that shocked the nation and prompted many schools to adopt new safety protocols.

The shooter was identified as Adam Lanza, 20, according to CBS News. Lanza apparently walked into the school carrying multiple weapons, and shot 20 children in two classrooms. He then fired at several other adults in the school, including the principal, who was killed. The shooter reportedly shot and killed himself inside the school. Police found the body of his mother at a house in town, and attributed her death to Lanza as well, according to news reports.

“It was horrendous,” parent Brenda Lebinski, who rushed to the school where her daughter is in the third grade, told Reuters. “Everyone was in hysterics – parents, students. There were kids coming out of the school bloodied. I don’t know if they were shot, but they were bloodied.”

Governor Bob McDonnell, of Virginia, was among many public officials expressing their condolences yesterday. “Unfortunately, Virginia has our own painful memories of the tragic shootings at Virginia Tech in 2007. Those memories will never fade, and we continue to grieve for all those lost on that April day,” he said. “We are all too aware of the impact that events like this can have on a community.”

The president was preparing to address the nation this afternoon. The Hechinger Report will publish reactions and updates as the day goes on.

Update:

The president gave an emotional speech in reaction to the shooting—pausing to gather himself and wipe tears from his eyes before saying that most of the dead were between the ages of five and 10.

“I know there’s not a parent in American who doesn’t feel the same overwhelming grief that I do…Our hearts are broken today,” he said. “This evening we’ll do what every parent in America will do, which is hug our children a little tighter.”

He also said that “as a country we have been through this too many times,” and suggested lawmakers would have to come together to come up with policy to prevent future shootings.

The shooting is likely to revive a debate about gun control. The president has largely avoided the topic during his tenure as president. During the presidential campaign, a voter confronted the president and his Republican rival, Mitt Romney, during a town hall debate about whether they support renewing a ban on assault weapons.

At the time, the president said he supports a ban—although he wasn’t necessarily enthusiastic about it. “Part of it is seeing if we can get an assault weapons ban reintroduced,” he said. “But part of it is also looking at other sources of the violence, because frankly, in my hometown of Chicago, there’s an awful lot of violence, and they’re not using AK-47s, they’re using cheap handguns.”

Update:

Governor Dannel Malloy of Connecticut addressed reporters this afternoon in an outdoor news conference. “You can never be prepared for this kind of incident,” he said during his brief remarks. “What has transpired in that school building will leave a mark on this community.”

Paul Vance, of the Connecticut State Police, said that in addition to the 18 children who were pronounced dead at the school, two others died on the way to local hospitals. Another adult was found dead elsewhere, not in the school, but was believed to be a victim of the same shooter, bringing the total number of victims to 28. Vance said the shooting had been confined to two rooms in the school. “It’s a tragic scene,” he said.

The police said they were still reconstructing what happened, and did not offer many details, but an eye witness, who was allowed to enter the area because she’s a nurse, described the scene at Sandy Hook this morning to CBS News.

“When I got there, there was a lot of parents pulling in at the same time. I just ran up and the police where already there. They let me go because I told them I was a nurse. At the time, we thought we might have some victims that needed to be worked on and resuscitated.

“The people that were shot that were able to get help were taken out immediately so before I got there. I didn’t see anyone taken out in an ambulance. And then there was just a long wait. I don’t know, I kind of lost track of time but maybe like a two hour wait. We just saw SWAT teams go in and the canine unit go in and police surrounding the place and going into the woods, but nobody coming out.

“They wouldn’t even let us in the building. All I can say is, one of the cops said it was the worst thing he had seen in his entire career. But it was when they told the parents. All these parents were waiting for their children to come out, they thought that they were still alive. There was 20 parents that were just told their children were dead. It was awful.”

Update:

Children who survived the shooting have appeared on several television stations describing what they saw. One boy spoke to a CBS reporter about hearing bullets before a teacher grabbed him and pulled him into a classroom. But some experts and journalists are questioning whether interviewing children in this kind of traumatic scenario is necessary and ethical. “What little bit of detail these ‘witnesses’ have to offer doesn’t seem to be worth the insensitive nature of the questioning,” writes Rebecca Greenfield on the Atlantic‘s website.

An unidentified nine-year-old told the New York Times: “We were in the gym, and I heard really loud bangs,” he said. “We thought that someone was knocking something over. And we heard yelling, and we heard gunshots. We heard lots of gunshots. We heard someone say, ‘Put your hands up.’ I heard, ‘Don’t shoot.’

(This story has been updated to reflect new information as of Monday, December 17.)

Giving teachers more power helps in turnaround of Boston schools

Six low-performing Boston schools participating in a pilot program that gives teachers more training, support, and leadership roles are showing higher growth on state tests than other low-performing city schools according to a report released Monday by the non-profit Teach Plus.

The T3 Initiative program, a collaboration between Boston Public Schools and Teach Plus, began training and placing groups of experienced teachers with track records of raising student test scores in a set of three failing schools in 2010, after a dozen city schools were deemed underperforming by the state in 2010 for chronically low test scores. The pilot expanded to three more schools the following year.

The report, an evaluation by Teach Plus of its own program, shows that at the first three schools to use the program, the percentage of students earning advanced or proficient scores on their state tests increased by nearly 13 percentage points in English language arts on average over the course of two years, and 16.5 percentage points in math on average. The second group of schools saw similar growth at the middle school level over the course of one year.

In addition to training and hiring new teachers, the six schools in the T3 Initiative, provided health and wellness services for students, and intensive teacher professional development over the summer. Teach Plus teachers make up 25 percent of the school faculty at T3 schools, and serve in leadership roles to help other teachers improve.

Six other Boston turnaround schools did not participate in the T3 pilot, but did experiment with longer school days and staffing changes. A report by The Massachusetts Board of Elementary and Secondary Education found that state-wide, less successful turnaround schools, including those not part of the T3 program, tended to provide more generic professional development, infrequent coaching and teacher support, and struggled to create a safe school environments. Test scores at those turnaround schools have remained relatively stagnant.

Among the T3 schools, the biggest gains were in the middle grades at Orchard Gardens K-8, which doubled the number of seventh graders scoring proficient in English and math over the course of one year. At the elementary schools participating in the program, growth has been high in math, but more moderate in English language arts. There was only a 0.3 percentage point increase on average in English language arts scores during the first year of the pilot. The elementary school that joined the program during the 2011-12 school year saw only 4 percentage points of growth, although math scores jumped by 18 percentage points.

The Teach Plus program is among several types of reforms that Boston has tried since the 12 city schools began receiving federal funding to undergo a turnaround process. Principals were replaced in five of the 12 failing schools, and staff members at six of the schools were asked to reapply for their positions, including three schools that participated in the T3 project. One school closed in 2011 as part of a massive school closure and consolidation plan intended to save the district more than $36 million. Nine of the remaining 11 schools extended their school day by an hour, and two added two hours.

Research suggests that school turnarounds are extremely difficult. Most schools in the federal School Improvement Program, which the Boston schools were a part of, made gains on test scores in the first year, but more than a third did worse after receiving federal funding to make improvements.

“If we’re going to make lasting change in our schools, we need to look to teachers to lead that change,” said Boston Public Schools Superintendent Carol R. Johnson. “We’re thrilled with the progress these schools are making.”

Research has shown that teachers are the most important in-school factor that influences student achievement, yet inexperienced teachers are more common in urban and low-income schools. A 2010 study commissioned by the Massachusetts Business Alliance for Education found that during the course of two school years, half of Boston’s public-school teachers were never evaluated, and a quarter of the city’s schools didn’t turn in teacher evaluations to the district.

Districts in Massachusetts have three years to turn around failing schools before they could face a state takeover.

Clock ticks down on billions in tuition tax credits

Among the many tax breaks waiting for Congress to rescue or let tumble off the fiscal cliff is more than $18 billion in savings for families who pay college and university tuition.

The American Opportunity Tax Credit expires on December 31st, and, with it, financial relief averaging $1,545 per recipient who pays for college.

Compounding the dilemma is the fact that an increasing portion of these tax breaks goes to families whose adjusted gross income is between $100,000 and $180,000, according to calculations by the College Board.

They get 23 percent of the savings, or $4.3 billion a year. In all, 39 percent of the tax break, which was meant to help low-income students, is being steered to families who make $75,000 or more per year.

The federal tax credit goes to about 4.5 million students and their families. They can deduct up to $2,500 of the cost of tuition, fees and course materials for the first four years of attending a postsecondary educational institution.

Read more here about the billions in financial aid going to college students who the government says don’t need it.

Charter schools expanding rapidly in more U.S. cities

Charter schools now enroll more than 20 percent of public school children in 25 school districts across the country, according to a new report from the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools, which tracks charter-school growth annually.

Overall, charters enrolled more than two million students in 41 states and the District of Columbia during the 2011-12 school year; that amounts to about 5 percent of public school enrollment nationally.

In only one community, New Orleans, did charters serve more than half of the public school children last year. But the data suggest that within the next few years, charters will likely educate a majority of students in other communities as well. For instance, charters enrolled 41 percent of students in both Detroit Public Schools and the District of Columbia Public Schools in 2011-12. Seven other communities experienced growth greater than 25 percent in charter-school enrollment between 2010 and 2011.

Apart from New Orleans, Washington, D.C., and a few other Southern cities, Midwestern towns dominated the top 10 list.

The report cites parent demand as a major explanation for charters’ growth. But President Barack Obama’s Race to the Top program also motivated some states to lift or eliminate their caps on the number of charter schools allowable under state law.

For more background on the history and politics of charter schools, please see this Education Writers Association guide.

Districts serving the highest percentage of charter school students (2011-12):

New Orleans Public Schools (Louisiana), 76 percent

Detroit Public Schools (Michigan), 41 percent

District of Columbia Public Schools, 41 percent

Kansas City, Missouri School District (Missouri), 37 percent

Flint City School District (Michigan), 33 percent

Gary Community School Corporation (Indiana), 31 percent

St. Louis Public Schools (Missouri), 31 percent

Cleveland Metropolitan School District (Ohio), 28 percent

Albany City School District (New York), 26 percent

Dayton Public Schools (Ohio), 26 percent

San Antonio Independent School District (Texas), 26 percent

Indianapolis Public Schools (Indiana), 25 percent

Roosevelt School District 66 (Arizona), 25 percent

Toledo Public Schools (Ohio), 25 percent

Youngstown City Schools (Ohio), 25 percent

Adams County School District 50 (Colorado), 23 percent

Grand Rapids Public Schools (Michigan), 23 percent

The School District of Philadelphia (Pennsylvania), 23 percent

Milwaukee Public Schools (Wisconsin), 22 percent

Phoenix Union High School District (Arizona), 22 percent

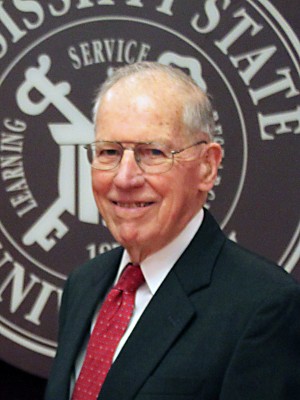

Why change is still a long time coming in Mississippi education

For education advocates in Mississippi, it must be difficult to sit quietly and watch the tepid progress, or, as some put it last week, “small scale ideas” that are emerging in a state with a perpetual education crisis.

After all, it’s been 30 years since the so-called “Christmas Miracle” — the historic December day when former Democratic Gov. William Winter convinced lawmakers in a special session to pass Mississippi’s $106 million Education Reform Act.

I listened to Winter’s fascinating reflections on that moment in history in this 2004 story on National Public Radio. Perhaps most astonishing was the timing. Mississippi had not yet embraced or come to terms with school desegregation, so there seemed little hope in getting it passed.

Yet pass it did, establishing statewide, publicly funded kindergarten and a compulsory school attendance law for the first time.

Former Secretary of State Dick Molpus, who was director of federal programs for Winter, noted at the time: “We broke the back of the status quo in this city forever.”

Crusading journalist Carl Rowan said the education act would “give the children of that state a more reasonable chance at a decent education and lift Mississippi out of the ignominy of being the worst-educated and most backward state in the union.”

Thirty years later, though, Mississippi remains the only state in the South without publicly funded pre-kindergarten. This year will be no different, according to the budget proposed by Republican Gov. Phil Bryant, who wants to prioritize teacher merit pay, literacy and dropout prevention. The legislative session begins next month.

Bryant’s agenda does not satisfy Winter, who said last week that the state’s current leaders do not have the necessary political will to make far-reaching changes.

“I do think we have lost our momentum,” Winter said, in remarks quoted in the Jackson Clarion-Ledger, during a forum to discuss the 30th anniversary of the act at Millsaps College. “We’ve lost that political will to do the hard things that must be done. They can’t be done without more investment in public education.”

Supporters of Bryant, though, may be equally frustrated, noted Clarion-Ledger columnist Sam R. Hall.

“As comparisons of the two were made, Bryant supporters said we’ve tried Winter’s way for 30 years, and we still have failing public schools,” Hall’s column noted.

Here at The Hechinger Report, we are continuing to spend time examining education problems and potential solutions in Mississippi, which suffers from the highest rate of childhood poverty in the country. Students still post some of the lowest scores on standardized tests, and often must repeat kindergarten or first grade.

In 2011, the state’s fourth-graders were outperformed on the reading portion of the National Assessment of Educational Progress by their peers in 44 states. In math, they finished second to last in the nation, ahead only of fourth-graders in the District of Columbia. Just 61 percent of Mississippi’s students graduate from high school on time—more than 10 percentage points below the national average.

Bryant’s budget does contain some education initiatives, including $3 million for what up until now has been a privately funded program called Building Blocks.

Molpus calls Bryant’s proposals—which will likely be discussed a great deal, along with a new push for charter school legislation — “baby steps.”

The Hechinger Report will be following what happens in next month’s legislative session, and hopes to speak to both the former and current governors and learn more. Columnist Hall is hopeful and believes that even Winter might be satisfied.

“If lawmakers work together and advance key provisions from both sides, then lawmakers could pass the first meaningful education reform this state has seen in 30 years,” Hall noted. “It could even eclipse the work done by Winter, something I’m sure he would welcome if it meant a better future for Mississippi.”

New graduation data shows lower rates, wide achievement gap

New federally-compiled graduation rates for 47 states and the District of Columbia left many states reeling this week as more rigorous and uniform standards highlighted wide achievement gaps and lower numbers than previously reported.

While the U.S. Department of Education said the new rates can’t be compared to previous numbers, officials said the graduation rates provide an accurate ranking of states. Georgia, which has previously boasted graduation rates of about 80 percent, found itself near the bottom, with a graduation rate of 67 percent, even lower than neighboring states Alabama and Mississippi. “It’s disappointing,” Tim Callahan, spokesman for the Professional Association of Georgia Educators, told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. “We were using sort of a feel-good calculation.”

And in Ohio, where state-calculated graduation rates have been climbing for several years, the state’s interim superintendent Michael Sawyers told the Newark Advocate that he’s “surprised and somewhat disheartened” to see that the graduation rate for black, Hispanic and low-income students is far lower than the 85 percent rate for white students. New Jersey, which had the highest graduation rate in the nation in a ranking by Education Week in June, tied with six other states for 12th place. “I’m not sure there is any material difference between being in the top 12 versus the top eight,” said State Education Commissioner Chris Cerf to The Record. “It shows New Jersey is doing extremely well compared to the rest of the nation, and has significant room to improve.”

The move to a uniform system reflects a broader trend in education reform, as states also launch the new Common Core State Standards, which will allow more accurate comparisons of academic achievement. Under the new graduation metrics, all state scores are based only on the percent of students who graduate in four years, and data is adjusted for students who drop out or do not earn a regular diploma. Previously, states or outside agencies often included all students that graduated in any given year in calculating graduation rates, regardless of how long it had taken a student to finish.

The new data shows that even states with high graduation rates overall aren’t doing as well at graduating some student groups. Connecticut has an 83 percent graduation rate, one of the highest in the northeast. But when it comes to low-income students, only 62 percent graduate. (Connecticut also has one of the widest test score gaps in the nation between low-income students and their more affluent peers.) Minnesota has one of the largest gaps in achievement between black and white students, with a graduation rate for white students 15 percentage points higher than black. And in South Dakota, where 83 percent of all students graduate, less than half of Asian, Pacific Islanders, and American Indians earn their diplomas.

“By using this new measure, states will be more honest in holding schools accountable and ensuring that students succeed,” said U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan. “These data will help states target support to ensure more students graduate on time.”

The lowest graduation rate was in Washington, D.C., where 59 percent of all students, and only 39 percent of students with disabilities, graduate high school on time. But D.C. does a better job of graduating black students than Minnesota and Oregon, and graduates a larger percentage of low-income students than Nevada and Alaska, all states with higher overall graduation rates.

Several states have relatively stable numbers across racial and income lines. Iowa, which claimed the highest graduation rate of 88 percent, had little variation in rates for different student groups, as did Texas and Arkansas.

No consensus on which skills should be included in teacher evaluations

At least 30 states are launching new systems to evaluate teachers using more rigorous criteria about what makes a good teacher, but so far there is little consensus on what the criteria should be.

Teacher evaluations have become highly controversial as states introduce increasingly different models.

Can the quality of a teacher be measured by looking at just a few key skills, such as setting academic goals and running an effective class discussion? Or should teachers be evaluated based on a broader range of abilities, including lesson-planning and content knowledge?

In Los Angeles, teachers will soon be evaluated on a list of 61 criteria during classroom observations conducted by school administrators. Louisiana, by contrast, requires principals to look at just five skills in the observation portion of the state’s new teacher evaluations. In most classrooms in Tennessee, principals use a checklist that includes 19 skills during observations that are part of a new, more intensive evaluation system launched last year. In each place, a teacher’s rating will be based on a combination of classroom observations and student achievement data.

Both the longer and shorter observation checklists have met with criticism. The Los Angeles Times reports that while teachers participating in the roll-out of a new evaluation system planned for the Los Angeles Unified School District are generally optimistic about it, many administrators are concerned about the time it takes to observe and rate teachers on 61 skills. In Louisiana’s case, Charlotte Danielson, the architect of a longer checklist on which Louisiana’s observation tool is based, warned that the state’s truncated version is simplistic and may lead to lawsuits.

The Los Angeles checklist is also based on Danielson’s framework, but the district added extra skills to some of the evaluation areas to reflect the local context and California standards for teachers. And although the framework being piloted in Los Angeles is lengthy, the district is only focusing on a handful of areas while piloting the program this year, including “classroom climate” and “teacher interaction with students.”

These two indicators appear in other observation rubrics across the country, but the importance they are given in different rating systems varies. Florida’s Miami-Dade school district has also made teacher-student relationships a priority. There, teachers are rated on eight performance standards including “learning environment,” which holds more weight in the evaluation score than the standards evaluating professionalism and communication. In Louisiana, assessments and procedures, or the extent to which the class “runs itself” through routines, are the priority, and separate indicators measuring a classroom’s climate and learning culture were dropped.

Despite the lack of agreement about the details, the evaluations are becoming increasingly important as more states are using new evaluations to determine who can stay in the classroom. Under Louisiana’s new system, teachers could lose their certification if they receive an “ineffective” rating for two years in a row. In Washington, D.C., 7 percent of the teaching force was fired after a controversial new evaluation system was launched two years ago. (The District of Columbia Public Schools originally included a total of 22 standards in its observation framework, but dropped the number to 18 after teachers complained that the number of requirements was overwhelming.)

When the Measures of Effective Teaching project, a study in six districts funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, observed nearly 3,000 teachers using five different observation systems, researchers found that it didn’t really matter which practices were emphasized on an evaluation. Teachers who more effectively demonstrated the types of practices emphasized in any given system had greater student achievement gains than other teachers. (Disclosure: the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation is among the many funders of The Hechinger Report.)

But educators and researchers say the observation process is not meant just to identify which teachers are high-performing. It’s also supposed to help low-performing teachers improve their practice. “The goal of supervision and evaluation should be to develop expert teachers who are self-correcting,” said Michael Toth, CEO of the Learning Sciences Marzano Center for Teacher and Leadership Evaluation, an organization that develops teacher evaluation tools, in a press release. Toth cited results of a study that found teachers assessed with more detailed observation tools are more likely to change their classroom practices. “The more specific the model is … the better the model will be in driving teacher development,” Toth said.

Some teachers in Los Angeles told the Los Angeles Times that their new evaluation system does just that by focusing on specific areas and encouraging collaboration and reflection. Last year, 450 teachers and 320 administrators tested the system. By the end of this school year, every principal and one volunteer teacher at each school in the district will be trained, with a district-wide roll-out date still to be determined.