Ed School & Med School: Training Teachers Like We Train Doctors?

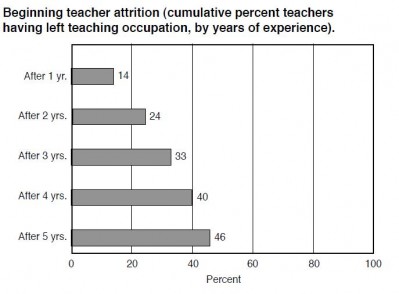

Turnover Among New Teachers (source: Richard Ingersoll)

NPR’s Claudio Sanchez had an interesting story on Thursday about the Boston Teacher Residency (BTR) program, which seeks to provide would-be teachers with the kind of intensive field preparation that would-be doctors receive during medical school rounds.

The former superintendent of the Boston Public Schools, Tom Payzant, founded the program in 2003. Seventy-five “residents” go through the program each year, many later filling hard-to-staff positions (special ed, science, math) in Boston public schools. Payzant likens his program to boot-camp.

Listening to the story, I was struck by the similarities between the Boston Teacher Residency program and the more traditional teacher-education program that I completed the same year BTR began. Both place future teachers in Boston public schools for “residencies,” both entail extensive student-teaching under the guidance of mentors, both require taking full graduate-school courseloads and both end in a master’s degree. My program, at Harvard, also had a distinct boot-camp feel to it.

Maybe my teacher-ed program is unusual in how it prepares future teachers, or maybe the BTR isn’t actually all that revolutionary or different from many teacher-ed programs. I suspect the latter.

Payzant certainly seems to think the BTR is up to something most ed schools aren’t: “Most teacher training institutions focus more on content and less on practice and how people teach,” Payzant says in the NPR story. But I wonder whether this sweeping statement is really true. It’s a common claim — one that Secretary of Education Arne Duncan likes to make, too — but I question its empirical basis. Duncan cites a 2006 study of ed schools by Arthur Levine, a former president of Teachers College, but his choice of quotations from Levine’s study makes a rather different point. Levine summarized his study thus: “The bottom line is that we lack empirical evidence of what works in preparing teachers for an outcome-based education system. We don’t know what, where, how, or when teacher education is most effective.”

So how much truth is there to Payzant and Duncan’s claims that most teacher-ed programs focus on content at the expense of practice? I’d say the current evidence is mostly ancedotal; as Levine points out, we don’t know much. And there are, no doubt, also things about teacher-ed programs that we don’t even know we don’t know.

Near the end of the NPR story, the reporter quotes the BTR’s program director, Jesse Solomon, saying his program is superior to most because its graduates don’t quit teaching as quickly as the graduates of other teacher-ed programs. (Nationally, it’s estimated that a third of new teachers quit the profession after just three years, and nearly half quit by the fifth year, according to the research of professor Richard Ingersoll.)

But the program director’s evidence is shaky. According to Sanchez, the NPR reporter, “85 percent of BTR’s graduates stay in the classroom much longer” than two or three years. Hmm. I wonder how “much longer” is being defined here. Given that BTR only began in 2003 — and thus its first residents didn’t graduate until 2004 — we should remember we’re only a few years removed from when they began their teaching careers. Thus, if the program’s first graduates remain in the classroom, they’re still only in their sixth year of teaching. Does that constitute staying in the classroom “much longer” than those who leave after 2-3 years?

The point is that Solomon’s claim has little empirical basis because BTR only dates back to 2003. (Therefore, half of the program’s graduates have yet to complete their third year of teaching.)

Simply put, not enough time has elapsed to determine whether retention rates differ significantly between BTR graduates and graduates of more traditional teacher-ed programs. It should also be noted that BTR graduates have an extra incentive not to quit right away: they are required to teach in the Boston Public Schools for three years after graduation. Quitters must retroactively foot the program’s tuition bill ($10,000).

Such residency programs likely have merit, but more and better research is needed before we declare them radically different from and superior to the more traditional teacher-ed programs out there.

Imagine a charter school company that wants it all

Charter schools are not all that hard to understand. Instead of being managed by a district bureaucracy, charter schools apply to an “authorizer” for permission to operate with public money. The authorizer may be the local school district, a university, the state itself or some other body. Just as a school district is governed by a school board that hires a superintendent and sets policies, charter schools are governed by a board that hires the principal. Or, the board hires a management company to operate the school. The management company should be answerable to the school’s board.

But, as a long front-page story in The New York Times explains, Imagine Schools, the largest charter school management company in the country, stacks the boards of its schools with pushovers and shills and company stooges. The Ft. Wayne Journal Gazette covered much of the same ground in a terrific three-part series that appeared last November. (One installment is here.) The authors of that series — Dan Stockman and Kelly Soderlund — laid out the whole story and have been reporting on the company ever since, leading to some changes.

The company profits big from the public money. What I liked about both stories was that they didn’t paint all charters with the same brush. The stories didn’t say that because this company was a bad actor, all charter management companies were bad actors. They didn’t say that charters were bad. The reporting was straight. Charter advocates ought to be pleased with these stories. They should help expose an operator that is doing charters no favors.

Did J.D. Salinger believe in unschooling?

J.D. Salinger

Or was the legendarily reclusive writer just spoofing us?

The last story in J.D. Salinger’s Nine Stories is called “Teddy” and it’s about a 10-year-old genius who fascinates scholars and religious figures. He’s asked about his views on education and he either endorses a radical form of progressive education or he makes fun of it. Anyone know? If he’s faking it, he’s a good mimic. Nothing worth knowing has to be taught. It can be absorbed when a child wants to absorb it. Teddy says:

“‘I know I’m pretty sure I wouldn’t start with the things schools usually start with… I think I’d first just assemble all the children together and show them how to meditate. I’d try to show them how to find out who they are, not just what their names are and things like that… I guess, even before that, I’d get them to empty out everything their parents and everybody ever told them. I mean even if their parents just told them an elephant’s big, I’d make them empty that out. An elephant’s only big when it’s next to something else — a dog or a lady, for example… I wouldn’t even tell them that an elephant has a trunk. I might show them an elephant, if I had one handy, but I’d let them just walk up to the elephant not knowing anything more about it than the elephant knew about them. The same thing with grass, and other things. I wouldn’t even tell them grass is green. Colors are only names. I mean if you tell them grass is green, it makes them start expecting the grass to look a certain way — our way — instead of some other way that may be just as good, and maybe much better… I don’t know. I’d just make them vomit up every bit of the apple their parents and everybody made them take a bite out of.’

‘There’s no risk you’d be raising a little generation of ignoramuses?’

‘… No! … Besides, if they wanted to learn all that other stuff — names and colors and things — they could do it, if they felt like it, later on when they were older. But I’d want them to begin with all the real ways of looking at things, not just the way all the other apple-eaters look at things — that’s what I mean.'”

It’s always eye-opening when educators (and developmental psychologists) equate teaching with limiting rather than enhancing a child’s knowledge and understanding. Those who follow this philosophy — a misunderstanding of the pragmatist philosopher/educator John Dewey — believe teaching corrupts a child’s natural instincts. Instincts and inspiration are more important than studying and working hard to learn things. In this view, children will learn what they need to learn when they need to learn it, and in whatever way they prefer to learn it. Followed to its conclusion, that idea leads to the ideology of unschooling. But, the question raised by Teddy’s interrogator stands. Wouldn’t we end up with a “generation of ignoramuses?”

(This post was revised on April 23, 2010.)

Teaching gun safety in schools creates quandary, raises questions

An interesting debate has emerged in Virginia, now that the Virginia General Assembly has directed the state’s Board of Education to develop materials for teaching gun safety to elementary school children.

The catch, according to an article in The Washington Post, is just what to incorporate into those lessons. The Assembly wants to include the National Rifle Association’s guidelines. Some amendments were included in the final version. Virginians for Public Safety — a group that works closely with families of the Virginia Tech shooting victims — does not want the NRA to supply all of the material for the lessons.

And there are larger questions, some of a more philosophical nature, notes Valerie Strauss of The Answer Sheet blog. Does it make sense, she asks, “for public schools to spend money on teaching gun safety when they are facing dramatic budget cuts?”

The Virginia General Assembly just approved a cut of $646 million in public school funding over the next two years, Strauss points out, adding that many schools are “struggling mightily to keep teachers employed.”

There are plenty of comments about the bill, w hich has generated a fair amount of controversy.

Fewer profits, more scrutiny at for-profit colleges?

For-profit colleges have undergone a great deal of scrutiny lately, in part because they are getting a second look from students at overburdened community colleges and in part because they promise to prepare students for paying jobs in the midst of a recession.

They’ve also been in the headlines a lot, most recently for exaggerating “the value of their degree programs, selling young people on dreams of middle-class wages while setting them up for default on untenable debts, low-wage work and a struggle to avoid poverty,” according to a recent New York Times article.

The association that represents some 1,400 members has been fighting back, in a series of letters and articles. The pushback, according to InsideHigherEd, comes as the U.S. Department of Education is poised to issue new regulations that would “assess vocational programs based on the ratio of their graduates’ student loan debt to their incomes,” the story notes.

The Career College Association has suggested instead that its programs provide prospective students “with more robust information on job placement and loan burdens to keep students from taking on untenable debt burdens.”

This debate is an important one to watch because it comes at a time when President Barack Obama has stated his desire for more U.S. students to earn college degrees. The Career College Association insists that their schools open doors for thousands of Americans to better jobs, credentials, training — and, of course, degrees.

But at what cost?

Just when you thought things couldn’t get any worse…

A new report from the Manhattan Institute and the Foundation for Educational Choice, “Underfunded Teacher Pension Plans: It’s Worse Than You Think,” is receiving a lot of media attention. Stories about the report have appeared in many outlets, including Education Week, USA Today, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution and Business Week.

Co-authored by Josh Barro and Stuart Buck, the report claims that teacher pension plans are significantly more underfunded than most people realize. Last week, in an opinion piece on Forbes.com called “The Teacher Pension Nightmare,” Barro spelled out just what this might mean for the country: “Pension and retirement plans all over America have lost value. Plans covering public school teachers, by their own admission, are underfunded by $332 billion. However, the plans’ real funding gap is far worse than their financial statements show, at nearly a trillion dollars — and you and I will bear the burden of covering their shortfall.”

Yikes.

Goodbye to “first in, last out”? Change is in the air

California Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger

That we live in tough economic times is something we hear and read every day. What people once hesitated to call a recession — for even the act of naming it tends to erode consumer confidence further — is now being called “the Great Recession.” State revenues are not expected to recover before 2014 or 2015, meaning that budget cuts will be with us for the foreseeable future. And state budget cuts almost always involve education, for spending on education is typically 40-50 percent of a state’s total expenditures. In California, between 52 and 55 percent of the State General Fund Budget is spent on K-12 and higher education in any given year.

Thus, we are now seeing a flurry of stories about teachers being laid off across the country. In many states, districts are required to inform teachers of their employment status for the next academic year by either March 15th or April 15th. Illinois expects to see 20,000 teachers laid off across the state, with nearly 4,000 employees cut from the Chicago Public Schools alone. And pink slips are aplenty around the nation: in California, for instance, 26,000 teachers received them this year, up from 16,000 in 2009.

Traditionally, teacher layoffs have worked according to the seniority principle: if you were the first teacher hired, you’d be the last laid off. Or, conversely, if you’re the most recent hire, you’ll also be the first to go.

Politicians, policymakers and even teachers themselves are now questioning the concept of seniority. Does it really make sense, they ask, to let enthusiastic young teachers go — especially when their students are outperforming the students of more senior teachers in the same school — simply because they were the last in the door?

Seniority is written into most teacher contracts, but that might be about to change. In California, Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger spoke about seniority yesterday at a Los Angeles middle school that last year lost more than half of its teaching staff because most were recent hires. The Associated Press had this report on Schwarzenegger’s speech: “‘Several teachers of the year have gotten pink slips. How can that happen if they are award-winning teachers?’ the governor told an auditorium full of cheering children. ‘It is very important we change the system.'”

A proposed law in California — Senate Bill 955, sponsored by State Senator Bob Huff (R-Diamond Bar) — would do away with seniority as a consideration when layoffs become necessary. The California Teachers Association is strongly opposed to the bill, which is set for a hearing in the Senate Education Committee today.

Elsewhere in the nation, a similar movement to ignore seniority when laying off teachers is afoot. In Washington, D.C., a tentative agreement between Schools Chancellor Michelle Rhee and the Washington Teachers’ Union would significantly reduce the role played by seniority in such decisions. The main factor would instead be a teacher’s evaluation from the previous year.

In New York City, a proposed state bill would give principals discretion about which teachers to lay off. In a widely quoted statement, NYC Schools Chancellor Joel Klein said, “Experience matters, but it cannot be the sole or even principal factor considered in layoff decisions. … We must be able to take into account each individual’s track record of success.”

While teachers’ union invariably oppose such changes, teachers themselves aren’t always united — in part because younger teachers don’t see why they should automatically be laid off when there’s evidence they are working harder and achieving better student results than some of the more senior colleagues.

Look for some groundbreaking changes in the near future about how teachers are laid off. “First in, last out” might itself soon be out the window.

Doing a better job of helping students catch up

Melinda French Gates, the co-chair of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, gave hundreds of leaders of the nation’s community colleges a pep-talk and a talking-to on Tuesday. The Foundation wants the colleges to do a better job of helping their students — 60 percent of whom need to take remedial classes — catch up. An excerpt:

“Either [community colleges] can keep doing what you’ve been doing, in which case you will gradually find yourself able to meet fewer and fewer of your students’ needs, or you can innovate,” she said. “You can educate your students according to new models that yield dramatically better results for a fraction of the cost.”

She also announced that the Foundation will award $53 million on top of the $57 million it has already spent to support innovative programs and encourage their diffusion. (Full disclosure: the Gates Foundation is one of the supporters of The Hechinger Report.)

How much math do math teachers need to know?

Deborah Loewenberg Ball, University of Michigan

Joanne Jacobs has a lively discussion going on about how much math elementary school teachers need to know. A new study out of Michigan State University finds that prospective elementary and middle-school teachers in the U.S. know very little math, especially compared to their counterparts in many other countries. For some parents who have tried to help their kids with homework, it’s likely disconcerting to discover that their child’s teacher may not know much more than they do.

Deborah Loewenberg Ball, dean of the University of Michigan School of Education, is the leading scholar on what math teachers need to know to teach math well. Yes, they need to know the math. But they also need to know it in a special way so that they can use students’ wrong answers to diagnose the flaws in students’ conceptual understanding.

Community colleges feeling the heat

Community colleges serve many purposes — vocational certificates, remediation, training for nurses and computer technicians, recreational courses and providing the first two years toward a baccalaureate degree. With so many missions, how should they be held accountable for results?

That was the topic of a discussion at the annual national meeting of community college leaders, reported on by Scott Jaschik of InsideHigherEd. The leaders of two-year colleges were leery. But one of those currently working on a prospective national accountability system — who also happens to be an emeritus president of a Connecticut community college — said it was important and had to make sense to those “who are on our backs.”