Has special-ed inclusion backfired?

While talking to someone with a strong background in speech pathology and literacy recently, I learned of an interesting theory: Inclusion for special-education students, this educator said, has “backfired.”

Now, she didn’t necessarily mean that special-education students should be quarantined from their peers or that the inclusion movement didn’t have good intentions — just that there have been some unexpected consequences since we’ve moved toward inclusion.

Samuel Habib, about whom the 2008 documentary "Including Samuel" was made, sits in his supportive corner chair and smiles at a friend at Shaker Road School in Concord, NH. (Photo courtesy of Dan Habib)

One of the biggest unforeseen effects is that students with special needs who spend the majority of their time in a general-education classroom — over half of the six million U.S. students with disabilities — are spending hours every day with a teacher who likely knows little about how best to teach them. Special-ed students might be mainstreamed with their peers now, but whether they’re getting a better, or even equivalent, education than before isn’t clear.

While others might not go so far as to say the whole model has backfired, many experts are concerned. In fact, while doing research for a recent article about emergency-certification programs for special-education teachers, I found myself having the same conversation with expert after expert. Yes, these emergency-certification programs were of serious concern to them, but of equal or greater concern to them was how few general-education teachers are prepared to work with the special-education students they’ll inevitably have in their classrooms.

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) of 1990 — which began as the Education for All Handicapped Children Act in 1975 — mandates that students must be educated in “the least restrictive environment,” meaning special-education students must spend as much time as possible in a general-education classroom, unless “the nature or severity of the disability is such that education in regular classes with the use of supplementary aids and services cannot be achieved satisfactorily.”

Some classrooms are led by a general-education teacher helped out by a special-education teacher, in a team-teaching model. In other cases, however, students with special needs receive instruction from specialists only a few hours a day or week in pull-out sessions. That is, many special-education students spend the bulk of their days being taught primarily by general-education teachers.

Yet a typical general-education teacher-in-training only takes one or two courses about special education. He or she gets a brief introduction to the subject — which might cover how to recognize various disabilities and how special education works — but doesn’t receive in-depth training.

According to a study released last year by the U.S. Government Accountability Office, 27 percent of programs that prepare elementary teachers and 33 percent of those that prepare secondary teachers don’t require a course exclusively focused on students with disabilities. Similarly, 42 percent of elementary programs and 49 percent of secondary programs don’t mandate field experience with special-education students.

And many of the schools that do require such classes have added them in recent years, meaning that teachers who’ve been in the classroom for a decade or more likely lack this background.

In a more perfect world, teacher-training programs would fully follow the philosophy of inclusion, and all would require dual-certification in general education and special education. Currently, only a minority of programs even offer dual-certification, according to Joanna Uhry, a professor in Fordham University’s Graduate School of Education.

She’s well aware, though, that this type of institutional overhaul is a daunting task. “I think it’s possible,” she said, but “I don’t know how to go about doing it.” Presumably, it would make teacher-training programs longer and more costly — not attractive moves in the current economic climate.

Performance pay for superintendents, not just teachers and principals?

At a time when teachers are under pressure to improve test scores and show what kind of progress their students are making, the superintendent of schools in Minneapolis has also decided to spell out exactly how the public can hold her accountable.

No doubt the recession and the state’s financial woes have contributed to the superintendent’s decision.

Beth Hawkins, who covers education for MinnPost, noted yesterday in a post on her “Learning Curve” blog that the Minneapolis School Board is poised to approve new performance benchmarks for Superintendent Bernadeia Johnson that could be truly groundbreaking. (The MinnPost’s coverage of education is part of an ongoing collaboration with The Hechinger Report.) Johnson was promoted from deputy superintendent to superintendent in February 2010.

Hawkins notes, “Johnson will be evaluated on the district’s academic progress, on the implementation of four district-wide projects and on her ability to strengthen Minneapolis Public Schools internal and external relationships. If she makes all of the goals, she’s in line for a $30,000 bonus.”

The contract is even more radical: Johnson has agreed to pay her own health-insurance premiums from her $190,000 base salary. And to be eligible for the bonus, Johnson must meet a series of goals, ranging from preparing more students for college to narrowing the district’s achievement gap, according to the Star Tribune.

Johnson’s arrangement comes at a time when leaders such as Gov. Chris Christie of New Jersey are pushing employees to give back some of their benefits. As part of his attempt to reform the state’s employee pension system, Christie wants employees to increase their own contributions.

The idea hasn’t been popular with teachers, who have accused Christie of attacking middle-class workers. School superintendents have also raised questions.

“A proposal that requires workers to get less, and do more, also needs to address how the state is taking care of its responsibility,” said Richard Bozza, executive director of the New Jersey Association of School Administrators.

The question now is whether Superintendent Johnson’s new contract will set a precedent nationally.

Obama’s back-to-school speech: “It’s about working harder than everybody else”

In his back-to-school speech today, in Philadelphia, President Barack Obama covered many of the same themes he addressed in last year’s more controversial talk. The main ideas were rather bland, if worthy: Stay in school; do your homework; show up on time.

This year, Obama also acknowledged the recession and how it might be affecting students’ personal lives. He then borrowed from the charter-school lexicon to tell students that poverty and family strife aren’t excuses for giving up on school:

Here is what I came to Masterman to tell you: Nobody gets to write your destiny but you. Your future is in your hands. Your life is what you make of it. And nothing – absolutely nothing – is beyond your reach. So long as you’re willing to dream big. So long as you’re willing to work hard. So long as you’re willing to stay focused on your education.

He continued: “You see, excelling in school or in life isn’t mainly about being smarter than everybody else. It’s about working harder than everybody else.”

That may be true, but it no doubt helps to have a livable income, and involved parents, and a decent school. The destinies of the kids at the Masterman School, where Obama spoke, are probably going to turn out pretty well given that their school is not only excellent but also highly selective.

Obama did give a nod to all of the efforts his administration is making to reform the other schools out there that, unlike Masterman, are struggling.

“It will take all of us in government – from Harrisburg to Washington – doing our part to prepare our students, all of them, for success in the classroom, in college, and in a career. It will take an outstanding principal and outstanding teachers like the ones here at Masterman; teachers who go above and beyond for their students. And it will take parents who are committed to your education,” he said.

He then veered a bit from the written transcript, noting that at Masterman, he was “speaking to the choir here.” Masterman is a positive example other schools can look up to, the president suggested — “the kind of excellence we have to promote in all of America’s schools.”

As others have suggested, it might’ve been more interesting for the president to speak at a school that wasn’t a Blue Ribbon winner, perhaps one of the bottom 5 percent of schools singled out for federal turnaround money. As the president indicated, kids in less successful schools are those most in need of hearing his message to stick with it despite the tough odds.

Defaults on student loans increasing, especially at for-profit colleges

(Photo by Gregory F. Maxwell)

At a time when jobs are scarce, it should come as no surprise that higher percentages of students are defaulting on their college loans. Default rates increased from 5.9 percent to 6.0 percent at public institutions, and from 3.7 to 4.0 percent at private colleges and universities, new U.S. Department of Education data show.

The news was worse at for-profit colleges, where the default rate rose from to 11.0 percent to 11.6 percent, according to a story in Bloomberg News and a press release from the U.S. Department of Education. For-profits have been under increasing fire lately. In a recent investigation, the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) found fraud or deceptive marketing practices at all 15 of the for-profits it scrutinized.

U.S. Education Secretary Arne Duncan was quick to single out for-profit schools on Monday.

“This data confirms what we already know: that many students are struggling to pay back their student loans during very difficult economic times,” Duncan said in the release. “… While for-profit schools have profited and prospered thanks to federal dollars, some of their students have not. Far too many for-profit schools are saddling students with debt they cannot afford in exchange for degrees and certificates they cannot use. This is a disservice to students and taxpayers, and undermines the valuable work being done by the for-profit education industry as a whole.”

The new data come at a time when for-profit colleges are lobbying hard against new regulations that would cut financial aid for programs that leave students in too much debt. The New York Times last week noted that for-profit college executives have been urging students to speak out against the new rules, and have been emailing members of Congress noting their opposition.

The main question that the for-profit world must answer, in the meantime, is just what kind of employment prospects are available for graduates of their diverse programs.

“Right now, there’s no information that tells us whether career education programs are delivering quality training for jobs,” Lauren Asher, president of the Institute for College Access & Success (TICAS), an advocacy group in Oakland, Calif., told Bloomberg News.

The higher default rates at for-profit schools are a reflection of the tough economic times as well as the financial well-being of borrowers — not of the quality of the institution, according to the Career College Association (CCA), a voluntary membership organization of accredited, private postsecondary schools, institutes, colleges and universities that provide career-specific educational programs.

“In a climate marked by near double-digit unemployment, it is not surprising that former students continue to find it more difficult to repay their student loans than they might in better economic times,” CCA president Harris Miller said in a press release on Monday.

Why teachers need more training in reading skills

Teachers may need more help teaching reading skills. (Photo: Tim Pierce)

As the U.S. pushes hard to reform its education system, it’s troubling to learn that three in 10 teachers failed a licensing exam in Connecticut on the science of teaching reading. The exam, according to a story in The Connecticut Mirror, emphasizes phonics, fluency and other skills needed to teach young readers.

Teachers have been asked to take the test in Connecticut because of State Board of Education concerns about poor performance of elementary school students in reading, particularly among low-income and minority students who are far below their more affluent and white classmates in reading and math. The test has nearly 200 multiple-choice questions and two essays, and, according to the story, “is designed to test knowledge of teaching methods that reflect a rigorous approach to reading instruction, including phonics.”

The low passing-rate of teachers in Connecticut comes at a time when educators are debating the best way to teach reading. Is specific skill-building more important than exposing children to lots of texts and literature? What combination achieves the best results? The story raises questions that are being debated everywhere from school districts to education schools.

Margie Gillis, a scientist at Haskins Laboratories, a New Haven research institute specializing in language and literacy, told the Mirror that too many teachers “walk into a classroom assuming they know how to teach children to read and find out that one survey course [in college] wasn’t sufficient.”

If schools and districts spend more time preparing teachers for the test, though, will the results translate to the classroom?

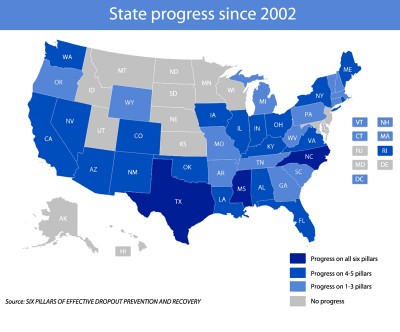

New reports on helping dropouts get back on track, preventing dropouts in the first place

Graduation rates at U.S. high schools have hovered around 70 percent for decades. But many urban and rural areas routinely graduate only 40 or 50 percent of their students. The dropout crisis in many cities is acute, with 2,000 high schools producing half of the nation’s dropouts. Cutting the dropout rate and turning around “dropout factories” are among the Obama administration’s priorities. But what strategies work? Earlier this summer, The Hechinger Report — in collaboration with the Washington Monthly — looked at how New York City, Philadelphia and Portland, Ore., have fared in their attempts to cut dropout rates.

Now, two new reports from Jobs for the Future (JFF) look at dropout prevention policies in all 50 states as well as what can be done for students who’ve already dropped out. Nationally, experts estimate that about 1.2 million students drop out each year, a figure so large it’s hard to wrap one’s head around it. Consider this: roughly 1.2 million students attend the public schools of New York City and Washington, D.C. — so imagine if all of those students quit in the same year. That is how big our country’s dropout problem is.

One of the JFF reports, “Six Pillars of Effective Dropout Prevention and Recovery: An Assessment of Current State Policy and How to Improve It,” looks at which states are doing which things JFF believes are critical to prevent dropouts and to get those who have dropped out back on track. The six pillars are:

1. Reinforce the right to a public education

2. Count and account for dropouts

3. Use graduation and on-track rates to trigger significant and transformative reform

4. Invent new models

5. Accelerate preparation for postsecondary success

6. Provide stable funding for systemic reform

On some of these fronts, many states have made progress in recent years. JFF identifies, for instance, 31 states that have taken action to reinforce the right to public education — by, among other things, raising the compulsory age of attendance to 18 or by stating that students have a right to a secondary education through age 21 or beyond. (States that don’t articulate such a right for their students, the report notes, have in the past given “explicit leeway to schools and districts to turn away older returning dropouts seeking a diploma if the district or school determines that they cannot ‘reasonably graduate’ by their 20th or 21st birthday due to age or lack or credits.” A footnote in the JFF report says that these states include Alabama, Florida, Illinois, Kansas, Rhode Island, Utah and Vermont.)

On other fronts, there has been little to no progress. Only 15 states have programs that “accelerate preparation for postsecondary success,” by which JFF means one or more of the following four options: dual enrollment, Advanced Placement, credit recovery and online learning. And just seven states have policies in place that foster the creation of new models for dropout prevention and recovery.

The other JFF report, “Reinventing Alternative Education: An Assessment of Current State Policy and How to Improve It,” spells out seven steps states could take to strengthen alternative-education options:

1. Broaden eligibility

2. Clarify state and district roles and responsibilities

3. Strengthen accountability for results

4. Increase support for innovation

5. Ensure high-quality staff

6. Enhance student support services

7. Enrich funding

Once again, many states appear to do some of these things relatively well already. Thirty-two states have taken steps to broaden eligibility guidelines, with the ideal intent of bringing “alternative education into the mainstream as a legitimate pathway toward obtaining high school and postsecondary credentials.” But not a single state presently has a policy in place to ensure high-quality staff in alternative-education programs.

Clearly, there is much room for improvement. The U.S.’s dropout problem will remain high on the agenda of politicians and policymakers across the country because the growing consensus is that a bachelor’s degree is the new high school diploma. Few people seem to believe that a middle-class lifestyle is realistic anymore in the U.S. without some kind of postsecondary training.

Can we “SIG” that instructional coach?

The acronym for School Improvement Grants – SIG – has become a verb at a middle school in Oakland, California, according to an illuminating blog post by an assistant principal there. In the post, assistant principal Kilian Betlach gives us insight into the chaos but also the hope that the Obama administration’s revamping of the SIG process has brought to Betlach’s school, Elmhurst Community Prep.

He writes: “Before last week’s State Board of Education decision that funded our school’s application, SIG wasn’t a verb, but rather a 4-letter word with etymology that centered on having a variety of unpleasant things done to you against your will.”

From his post, it sounds like things are looking up a bit, after a lot of confusion about whether the money was coming at all. But even with the assurance that his school will receive the grant, the picture he paints reveals a piecemeal effort to spend all the money — not a well-thought-out plan of action, which the grants were ostensibly meant to fund.

For example:

“Can you SIG an instructional coach?”

“Betlach, are we gonna SIG extra intervention teachers?”

“We need to SIG a whole new building.”

He concludes on a hopeful note – “I’m glad that we’ll be able to fund the hopes of teachers, families, and students. We’ve earned it” – but I’m left wondering if what’s happening at his school is happening across the country, and, if so, how successful SIG turnarounds will ultimately be.

Bridge programs can ease a tricky high-school transition

When I was an incoming ninth-grader, our bare-bones orientation lasted a few hours. Adults and students crowded into our school’s auditorium, as our principal took the mic to explain to us what a big journey we were embarking upon. Various teachers and student-leaders were paraded about on stage, and we were given the privilege of wandering the halls and scoping out the building.

I was terrified to start high school, and I can say with confidence that my orientation didn’t change a thing either way. (In fact, I still got lost on my first day, walking into a homeroom of upperclassmen before realizing I was on the wrong floor and scrambling down the stairs desperate not to be late.)

That night in our auditorium was an attempt to disguise the fact that, for the most part, the move to high school was sink-or-swim. We were thrown in head first — and, sure, we had guidance counselors and faculty members to whom we could theoretically turn for help in the first few weeks, but we didn’t really know any of them. And we were intimidated.

Despite what a big change it is for a 14-year-old to go from middle school to high school, the transition traditionally hasn’t been given much time or thought. That’s been changing slowly, and the movement seems to be gaining steam, at least for students at risk of dropping out. Summer-bridge programs, where students spend at least a week at their new school before the academic year officially begins, are growing in popularity, as The Hechinger Report found in a collaboration with The Seattle Times. These programs try to give students a little extra time to get comfortable in the high-school setting before the year begins. Other transition approaches, like ninth-grade academies, have also gained traction.

A similar move away from the sink-or-swim scenario can be found in U.S. colleges and universities. In order to improve retention rates, faculty and administrators are now focusing on the crucial first year, offering extended orientations and strengthening support-systems.

Summer-bridge programs actually began at the college level, and only decades later trickled down to the secondary level. Perhaps more high schools will follow in higher education’s footsteps and help freshmen (even those who, statistically speaking, are likely to earn a diploma) make the transition. At the very least, it’d be a welcome move to decrease the number of red-faced freshmen madly dashing to homeroom on the first day of school.

Recess round-up: September 7, 2010

A daily dose of education news around the nation – just in time for a little mid-day break!

All-girls school: A new single-sex charter school in Denver will focus on “empowering girls and providing them opportunities denied in a co-ed setting.” (Denver Post)

School turnarounds: The New Haven (Conn.) Register takes a look at school-turnaround models through the eyes of parents and students.

Race to the Top: The clock is ticking, as lawmakers and teacher-union members in Florida must work to hit tight deadlines for the federal grant. (Orlando Sentinel)

Charter schools: A new charter in Indianapolis offers dropouts the chance not only to re-enroll in high school, but to earn some college credit, too. (Indianapolis Star)

Texting: The Las Vegas Sun imagines what classrooms would look like if texting is incorporated into day-to-day instruction.

College tuition: In “the state’s boldest move yet,” Northern Arizona University is opening a new year-round campus, where students can complete their bachelor’s degree in three years — and for 41 percent less than the usual cost.

Recess round-up: September 3, 2010

A daily dose of education news around the nation – just in time for a little mid-day break!

‘STEM success’: Community colleges in rural areas are increasing the number of minority and women students in STEM fields faster than their urban and suburban counterparts. (Inside Higher Ed)

Principal-free school: Detroit is set to open Michigan’s first teacher-led school, replacing the principal and assistant principal roles with two lead teachers and an “executive administrator.” (The Detroit News)

Student achievement: Vermont is at the top nationally for low-income student achievement, but is at the bottom of the barrel when it comes to reform, according to the Report Card on American Education by the American Legislative Exchange Council. (Education Week)

Teachers’ unions: School will start on Sept. 8 as scheduled in Seattle, as union members ratified a three-year contract, which includes a “historic” agreement on teacher evaluations. (KPLU)

Federal funds: As Massachusetts begins to dole out Race to the Top and EduJobs money, some are complaining that the distribution is “uneven.” (Boston Globe)

Standardized tests: The Sacramento Bee asks: “Can you pass the STAR test given to kids?”