Building castles in the air: Visionary leadership

It’s hard to read Henry David Thoreau these days — almost 150 years after his death — and not think, “How quaint! How clichéd!”

It’s equally hard to remember that Thoreau’s insights weren’t considered clichés when he wrote them.

Clichés are a bit like retired professional athletes — spectacular at first sight, and really good for a long time, but eventually over-the-hill and not just tiresome but downright annoying. We wish they’d vanish altogether — and quickly.

Neuschwanstein Castle in Germany (photo by Softeis)

All of this to say that we should try to read Thoreau with 19th-century eyes, when he was at the height of his game and what he was saying had yet to be spun into bumper stickers and refrigerator magnets. With that in mind, let’s turn to the final pages of Walden and be blown away by Thoreau’s insights after two years, two months and two days in the relative “wilderness” of suburban Boston: “I learned this, at least, by my experiment; that if one advances confidently in the direction of his dreams, and endeavors to live the life which he has imagined, he will meet with a success unexpected in common hours. … In proportion as he simplifies his life, the laws of the universe will appear less complex, and solitude will not be solitude, nor poverty poverty, nor weakness weakness. If you have built castles in the air, your work need not be lost; that is where they should be. Now put the foundations under them.”

Building castles in the air is, of course, a favorite pastime of visionary leaders. Thoreau, rightly, emphasizes the importance of laying a foundation for the airy castle. It’s not enough to build the castle in the air. Without a foundation, such a castle will crumble.

But what Thoreau leaves unsaid is that building castles in the air — having a unique, inspiring, important vision — is itself incredibly hard work.

Clouded visions, or no visions at all, are the norm in many organizations — from financial institutions and political parties to nonprofits and schools. Why aren’t there more visionary organizations and leaders? How can a leader find a clear, compelling vision? These were the central questions of a recent BAM! Radio Network show I did with Margie Carter, the co-author of seven books on education, including The Visionary Director: A Handbook for Dreaming, Organizing, and Improvising in Your Center. Our host was Holly Elissa Bruno.

I suggested that our lack of visionary leaders is partly attributable to how we hire leaders, especially in the field of education: you get the job because in interviews you say exactly what the hiring committee wants to hear. (That is, to get the position, an incoming leader essentially compromises his or her vision and values — and perhaps only later realizes it’s impossible to change course much.)

In education, a school board often hires a superintendent with a mandate to produce fairly specific outcomes — lower the dropout rate, reverse declining enrollment, raise student achievement, reduce the power of the teachers’ union — and it typically has its own pet theories on how best to reach these goals. The superintendent, in essence, has been hired to implement someone else’s vision. And it’s very hard to be visionary when you have to work within the confines of someone else’s vision.

Changing course midstream is hard, of course, because you’re liable to be labeled spineless or directionless, as Holly Elissa Bruno pointed out. But it’s not impossible. To do so successfully, I believe leaders must be upfront about the change and why it’s not just good but necessary. The alternative — to pretend like you’re staying the course when you’re not, or to refuse to acknowledge missteps or mistakes — is a recipe for failure. Good leaders are unafraid to admit mistakes; they understand that doing so humanizes them to their followers, and that they’ll gain — not lose — credibility by being honest about their shortcomings.

Now, to return to the initial subject of clichés, I offer you parting thoughts from our radio show — Margie’s comes courtesy of Valora Washington, while mine is from a former president of Columbia University (who went on to become the country’s 34th president).

Valora Washington: “Transformation of the social order often begins with acts of imagination that elevate a startling dream of change above the intimidating presence of things as they are. Yet if such dreams are passionate and clear, and if they can call a great many people into their service, they may ultimately give shape to the future.”

Dwight D. Eisenhower: “Leadership is the art of getting someone else to do something you want done because he wants to do it.”

The ‘expectations gap’ is wider than the achievement gap

The Common Core State Standards, which so far have been adopted by 37 states and the District of Columbia, may seem like a good idea, but new tough standards won’t mean much if students in some states are only expected to learn 30 percent of the material, while students in other states are required to learn 80 percent.

A new study by the American Institutes for Research looks at the wide “expectations gap” across states and finds that “test results across the 50 states are not comparable, any inference about national progress is impossible, and we cannot even determine if progress in one state is greater than progress in another state.”

This is not necessarily a surprise — we’ve known for a while that some states use tests that are much easier than their counterparts in other states. But the report quantifies the variance, reporting that the gap between the states with the toughest expectations and those with the lowest expectations is twice the size of the achievement gap between white and black students.

A look at the extremes — Massachusetts at the top and Tennessee at the bottom — reveals just how large the gap is: Tennessee’s eighth-graders are expected to perform at the level of Massachusetts’ fourth-graders.

Ideally, the common core standards are supposed to address such problems. But the report authors argue that the content standards will eventually have to be matched with common performance standards, too:

“In order to reduce the expectations gap, this report recommends that the current standard-setting paradigm used by the states be reengineered. Rather than deriving performance standards exclusively from internal state content considerations, the report recommends a new method for setting standards that is influenced more by empirical data.”

For the full report, click here.

Education research vs. education policy

The debate about how (or whether) to consider student achievement when evaluating teacher performance appears to put policy makers and some of the leading scholars in the field on a collision course. As the matter of whether New York City should release the ratings of 12,000 teachers based on their students’ test scores goes before a judge, a group of scholars is seeking signatories to a petition that declares: “Legislatures should not mandate and districts should not pursue a test-based approach to teacher evaluation that is unproven and likely to harm not only teachers but the children they instruct.” The authors are some of the most highly regarded and recognized leaders in education research and include five former presidents of the American Educational Research Association as well as the elected leaders of other professional groups in the field.

But aren’t they too late? Twenty-five states and hundreds of districts already allow or are using measures of student achievement in teacher evaluations, which affect decisions about compensation and in some cases removal. So, are the scholars fighting a forest fire with a garden hose and refusing to acknowledge that reality? Well, maybe not.

The statement says test scores should not be “heavily relied on” and that value-added measures — which use sophisticated formulas to calculate the discrete impact of a student’s teacher — should not be used as the “primary way” to evaluate teachers. The petition says test scores “are one piece of information for school leaders to use to make judgments about teacher effectiveness” and “such scores should be only a part of an overall comprehensive evaluation.” That’s exactly how the system in New York is designed. Student achievement counts for less than half of the evaluation. So, is that “heavy reliance”? It’s certainly not the “primary way” that teachers are being evaluated.

School Pride gives hope — and mixed messages

It’s a familiar argument by leading education reformers: school improvement isn’t about the bricks and mortar, it’s about the people in the classroom. NBC’s School Pride takes an entirely different approach, though. The new reality makeover show features a comedian, journalist, SWAT commander and former Miss USA as they head to schools that are falling apart to rebuild them in just 10 days with the help of students, teachers and other volunteers.

It’s a familiar argument by leading education reformers: school improvement isn’t about the bricks and mortar, it’s about the people in the classroom. NBC’s School Pride takes an entirely different approach, though. The new reality makeover show features a comedian, journalist, SWAT commander and former Miss USA as they head to schools that are falling apart to rebuild them in just 10 days with the help of students, teachers and other volunteers.

The pilot doesn’t mention a single statistic about Enterprise Middle School in Compton, California, the first school slated for a makeover. Not its test scores (just 33 percent of students were proficient or advanced in English and math in 2008-2009); not the school’s suspension rate (27.7 percent); not the percentage of students on free or reduced-price lunch (71 percent in 2007-2008); not even its size (624 students).

Instead, we are meant to know this is a failing school because there are gophers in the football field, broken water fountains, bugs, leaky roofs and a dozen different comparisons you can make to prison. It’s obviously a school in need of repair.

No one would begrudge these students and teachers the opportunity to have their school completely renovated. Indeed, there are several touching moments that show what a difference some paint and bookshelves can make –- if in nothing else but attitude.

Although it’s never acknowledged on air, Executive Producer Denise Cramsey is under no illusions that a simple makeover can solve all of the problems our schools face.

“Fixing the school environment is not going to fix education,” she told the New York Times. “But studies prove that a better learning environment does lead to better learning.”

But it seems like School Pride can’t quite decide if this is the type of change that can happen anywhere any time, or something that needs the weight of a multibillion-dollar corporation like NBC behind it.

When volunteers check in on day one, a plastic container is on the table for any donation they feel like contributing, and SWAT commander Tom Stroup goes to a local construction company to ask for help — making it clear that they won’t be paid for the work. At the same time, big-name sponsors like Home Depot, Wal-Mart and Microsoft covered most of the renovation costs and, in return, were rewarded with product placement on prime time TV, the Times says. (Indeed, Microsoft’s logo is painted above at least one doorway in the renovated school.) It’s not exactly the kind of deal individual schools could cut on their own.

A science teacher early on in the show declares, “We really need someone from the outside to come and help us rebuild our school.” But journalist Jacob Soboroff — on a quest to determine who is to blame for the state of our schools — declares, after an interview with California Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger, that “People have the power to change their own schools and their own community and take charge of their own education.”

As Schwarzenegger points out, there’s a long list of potential people to blame (including the government, he says.) The truth is, there’s no easy answer. Perhaps that’s why it’s also unclear who should — and, more importantly, could — provide solutions as well.

Gwinnett County, a model for the nation to follow?

Georgia, as a second-round winner in President Barack Obama’s Race to the Top competition, was already getting some attention for its ideas on education reform. For one thing, it’s among the few states that participated in the competition that plans to use some of its funding to pay for early education initiatives.

Today, the state is getting more attention with the announcement that Gwinnett County, a suburb of Atlanta, has won the $1 million Broad Prize for Urban Education, which funds college scholarships for high school students. The county has outperformed similar districts in the state and also has one of the smallest achievement gaps. It was a finalist for the prize last year.

This year’s four finalists, each of which will receive $250,000 for college scholarships, are the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools in North Carolina, the Montgomery County Public Schools in Maryland, the Socorro Independent School District in Texas and the Ysleta Independent School District, also in Texas.

Gwinnett County, Georgia’s largest district, was already making a name for itself, at least locally. A recent analysis by the Atlanta Journal-Constitution which looked into the county’s success noted that it “defies the odds against long-serving school boards and superintendents.” The superintendent there has served for 14 years, far longer than the average tenure of a big-city superintendent, which is about three and a half years. In addition, four of the five school board members in Gwinnett County have served at least 13 years each.

With much education reform focused right now on shaking up schools in order to bring improvements, Gwinnett County seems to be an example of an effort where change is not necessarily the best or only strategy for improvement. As the AJC put it in its analysis of Gwinnett, “stability is paying off.”

Demographically, however, Gwinnett is in major flux. A couple of decades ago, the county was 90 percent white, according to USA Today columnist Don Campbell. Today, more than 100 languages are spoken in the schools, which are now majority black and Hispanic. Alan Richard, director of communication for the Southern Regional Education Board in Georgia, said Gwinnett is proof “that diverse communities in the South can have excellent schools.”

The fact that the schools have successfully handled their rapid transformation is something the nation, which is headed in the same direction, should perhaps examine even more closely.

Are charters holding students back at high rates and, if so, how might that affect their outcomes?

In an article published in the November 2010 issue of The American Prospect, The Hechinger Report takes a look at whether charter schools tend to hold students back more often than regular public schools do, and what that might mean for student outcomes. The research on retaining students – particularly if they’re older – has linked the practice to lower achievement and higher dropout rates. But it could be that charters are different than large districts that choose to end “social promotion,” the practice of passing students to the next grade level even if they’re low-performing, in order to keep them with peers of the same age. We looked in detail at the research and at what is happening in two charter schools in New York City.

Here’s an excerpt from the story. To read the entire piece, visit The American Prospect online or buy the Nov. 2010 issue.

In keeping with their focus on rigorous academics and accountability, many charter schools have adopted strict “retention” policies requiring struggling students to repeat a grade when they don’t meet expectations, sometimes even if they’re just a point shy of passing. Amari’s experience has become common in some of the highest-performing charter schools across the country. Charter-school advocates say this allows them to help students who are far below grade level to catch up. It may also give charters an edge over regular public schools on test scores. Even so, retention policies have gotten little attention in the debate over whether to expand the number of charters, although strict student-retention policies flout the education research. Studies have found that in the long term, students who are held back in middle or high school learn less and are more likely to drop out.

Although there are no national statistics tracking the percentage of students held back in charters, there is evidence that the number is large. Schools in charter hotspots like New York and Houston report retention rates as high as 23 percent, much higher than the district averages, which range from 1 percent to 4 percent. Margaret Raymond, director of the Center for Research on Education Outcomes at Stanford University, which conducted a major national study on charter-school performance, says she’s observed that charter schools tend to hold students back at higher rates than regular public schools. And a recent national study by Mathematica, a research firm based in Princeton, New Jersey, found that a sample of KIPP middle schools, the biggest charter network in the country, had a significantly higher retention rate than traditional public schools.

High retention rates can help to boost test scores at charter schools, at least in the short term. Students may do better on tests the second time, and retained students’ scores are dropped from their cohort, so a class of students could improve its test scores over time because the lowest performers have been removed. And sometimes low performers simply leave the charter school when they find out they’re going to be held back. While retention may help schools look better, the price may be students’ long-term success.

A NOTE: This story used data from New York City collected by Kim Gittleson of Gothamschools.org, who wrote about attrition and retention rates in an earlier blog post on that site.

We need fewer, not more, college grads? Really?

One surefire way to get people’s attention is to say the exact opposite of what everyone else is saying — to claim that conventional wisdom is wrong.

And sometimes, of course, conventional wisdom is wrong. This was one of the themes of Freakonomics, the hugely popular book by Stephen Dubner and Steven Levitt that went on to become a New York Times blog and now a documentary.

Conventional wisdom once held that the world was flat. Oops. Conventional wisdom also once held that cigarettes weren’t carcinogenic. Wrong again.

In the field of education, the belief that poor students couldn’t learn was once prevalent, as Jay Mathews pointed out in a radio show I was on this week. Also in education, there’s been the occasional claim that we need fewer students, not more, going to and graduating from college. This was a central claim by Charles Murray in his recent book Real Education: Four Simple Truths for Bringing America’s Schools Back to Reality (2008). Murray says too many people are going to college, and that ultimately this is very detrimental to the U.S. economy. (Forget not that Murray himself is not just a college graduate — of Harvard, no less — but also the holder of a Ph.D. from MIT.)

Now we have the deputy editorial-page editor of Cleveland’s Plain Dealer, Kevin O’Brien, saying the same thing. In an op-ed entitled “Ohio is stuck on what ‘everybody knows,'” O’Brien writes that “everybody knows” we need more college graduates — and that “everybody knows” college graduates earn more than high school graduates, and that a more educated workforce would make Ohio a more attractive place for businesses.

Trouble is, he doesn’t buy any of it. What “everybody knows,” O’Brien says, is actually nonsense.

He concludes with the following flourish:

Ohio already has more college students, more college graduates, more college teachers, more college administrators, more college departments, more college majors, more college courses and more college campuses than it needs. The proof of that is found in the inability of many graduates to find jobs — especially the jobs for which they ostensibly have been prepared — in Ohio when they graduate.

What Ohio needs is a chainsaw just for red tape. What Ohio needs is a right-to-work law. What Ohio needs is energy whose cost isn’t artificially inflated by government-mandated green fantasies. What Ohio needs is the return of some good, old-fashioned, dirty industry — the kinds of jobs that employ kids who aren’t cut out for college.

You’re not going to hear those truths from people who run for office, though. Ohioans aren’t ready for them. Everybody knows that.

Hmm. I’m not convinced.

On one point, at least, O’Brien is plain wrong. He writes, “Everybody knows the stats on earnings potential for college graduates vs. high school graduates — the stats that don’t factor in the effect on earnings potential of starting one’s working life $60,000 in debt.”

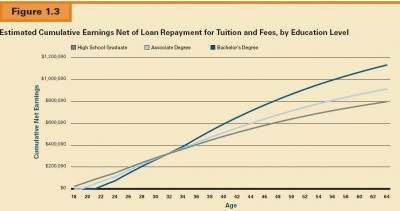

Actually, a recent College Board study called “Education Pays 2010: The Benefits of Higher Education for Individuals and Society” did precisely this calculation, taking into account both the fact that college graduates enter the workforce in debt and that they sit out of the workforce, on average, four years. The study’s conclusion? The break-even point is age 33, after which college graduates’ estimated lifetime earnings shoot past those who haven’t earned college degrees.

If average life expectancy in the U.S. were under 33 years, then, yes, O’Brien might be right on this point. But average life expectancy in this country is about 78 years. If we’re likely to spend much of our lives working — and most of us are, I’m afraid — then it seems inarguable that getting the education we need to do rewarding, well-compensated work is a sound investment. Conventional wisdom in this instance might well be right.

Education insiders: No lasting impact of Waiting for “Superman”

In a segment called “Waiting for Superman: Fact or Fiction?” on the BAM! Radio Network this Monday, education historian Diane Ravitch and four members of the media (including yours truly) discussed Davis Guggenheim’s latest documentary, Waiting for “Superman.”

Our host, Errol St. Clair Smith, wanted to know whether we thought the film would lead to productive discussions about how to reform public education in this country. Is there an emerging consensus in education reform today?

If so, Diane Ravitch suggested it’s not a good one. She said that the reforms now being undertaken by the Obama administration aren’t terribly different from reforms that date back to the presidencies of Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush and George W. Bush. Ravitch, who’s been a fierce critic of Waiting for “Superman,” says the film pushes the “conservative, right-wing [education] agenda” of the Obama administration.

Jay Mathews, of The Washington Post, disagreed. He sees many younger Democrats, even within the field of education, jumping on the Obama-Duncan bandwagon of education reform — and so he doesn’t think the agenda can be fairly labeled “conservative” or “right-wing” because those traditionally on the left are embracing it, too.

Ravitch said that she’s particularly troubled by a “false issue” that Guggenheim raises in the film, the notion that “teachers alone can turn around children’s performance.” She conceded that this does occasionally happen, but that it’s rare. Turning around how children do in school generally requires a much more comprehensive approach, which is something that the Harlem Children’s Zone (featured in Waiting for “Superman”) makes clear. Teachers are vitally important — no one denies that — but they can’t completely erase the effects of poverty (or homelessness, or lack of parenting, or insufficient healthcare and nutrition) on student achievement.

Toward the end of our discussion, Errol St. Clair Smith gave the five of us — Jay Mathews, Diane Ravitch, Valerie Strauss, Debra Viadero and me — a multiple-choice test on what the lasting impact of Waiting for “Superman” would be on U.S. public education. Four of us — all but Ravitch — opted for choice “D,” that the film would prove to be “another example that when all is said and done, much more will be said than done.” (Ravitch, ever the contrarian, picked “None of the above.”)

My parting thought on what U.S. education really needs was to be much more realistic in our expectations — that is, there’s no silver bullet that will magically (and quickly) cure all of our educational woes. Real reform, which is to say meaningful and lasting reform, happens incrementally much of the time. This is a reality we’d be wise to accept. The alternative is a fixation on the latest fads — doing dozens of reforms simultaneously, but never well and never thoroughly — which is also a recipe for lots of pretty rhetoric and superficial action but little lasting change.

Our best shot for getting better, I believe, is to recognize that small but substantial improvements over time add up. We should not discount incremental improvement. It might well take us a decade or two to have a radically better public-education system — but the upshot is that the progress would be dramatic and durable.

Rome wasn’t built in a day, as the cliché goes — and neither were the school systems in Finland, Singapore and South Korea, which everyone holds up as models to which we should aspire.

You can listen to our entire 20-minute conversation here. What’s your take on Waiting for “Superman”? Will anyone still be talking about the film in 10 years? In five years? In 2011? Will it catalyze education reform in the U.S.? What reforms are our public schools most in need of?

Venture capital for digital learning and technology

In a conference call with reporters today, Bill Gates announced that the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation will put up an initial $20 million to help colleges, non-profits, entrepreneurs and others to come up with new ways of using digital media in postsecondary education. (The Gates Foundation is one of the supporters of The Hechinger Report.) The Foundation is looking to speed the development of applications that serve one of four broad functions: combine face-to-face and online learning; engage students in learning through games, video, simulations and social media; make widely available new ways of teaching courses that many students fail; and keep track of students’ progress as they’re studying so that they can get real-time help tailored to their needs.

The “Next Generation Learning Challenges” will issue new RFPs every six to 12 months that target other needs and put up millions more in seed money. The range of online learning opportunities already in use is enormous, Gates noted. But, he said, many “are not fantastic,” are not engaging, and “are not better than learning in-person.” The RFP process, he said, is designed to find “some real gems beyond what we can become of aware of by going out and looking ourselves.”

A White Paper issued by the foundation mentioned as an example of personalized learning the Khan Academy where more than 300,000 users per month view short videos on topics in math, science and the humanities. (I just watched a nearly 10-minute video on the quadratic equation and was reminded of why math seemed so abstract to me in high school.) Gates said he’d like to support ways to make great lectures available “any time you want to watch” as well as ways digital media can improve remedial education by identifying students’ weaknesses so they know what to concentrate on in their studying.

Technology, he said, has the potential to speed up student learning and cut colleges’ costs in half. The larger goal of the effort, however, is more radical. New learning models will only take hold, the Next Generation White Paper says, “if policies that limit innovation—such as seat time requirements, student-teacher ratio requirements, and charter caps—are addressed.” Highly selective, high-priced colleges also should take note. Gates said he wants to find ways to take the lectures and high-end learning opportunities now available only by paying $50,000 per year in tuition and room and board “more broadly available at a substantial reduction in cost so it becomes affordable to lots and lots of kids—that is the dream.”

Seventy-five to a class — and proud of it!

“Average class size” – most of the time, it’s a statistic that schools with small classes eagerly advertise and schools with large classes bemoan, using the number as evidence that a given school system needs more money.

One middle school in Houston is bucking the trend, though. Average class size there is 75 students. And principal Lannie Milon Jr. wouldn’t have it any other way.

But there’s a catch: The large classes at Thomas Middle School all have between five to nine teachers, meaning that the student-to-teacher ratio remains low. Still, the sheer number of kids in a single space resembles a college lecture hall more than a traditional K-12 classroom.

And although team-teaching isn’t new, this strategy takes it to the next level, as the Houston Chronicle reports. Milon’s ideas have faced resistance from those who think the change is too radical a departure from traditional classrooms, but as the school year goes on, he’s converting many into believers.

Milon may be a forerunner in rethinking the concept of class size and what a class itself should look like. Although many are still focusing the debate on whether the conventional wisdom of “smaller is better” always holds true, some educators are looking at the potential benefits of putting many teachers and students in the same room.

For instance, as one source explained to me over the summer, by staffing a classroom with several teachers, not only can each individual play to his or her subject-area strengths, but entry-level teachers can work side-by-side with experienced teachers, learning from them. Also, special-education teachers can work seamlessly alongside general-education teachers.

It’s a fairly new idea, and questions about its overall effectiveness remain. Still, the experiment in Houston serves as a reminder that we’d do well to think of class size as a resource to be used strategically to educational ends, not as a hard and fast ceiling.

Some classes should be very small — think of pre-kindergarten, or a senior seminar in college. Others can easily be quite large — think of college lectures, where a star professor is assisted by a handful of teaching assistants. What works best in a given situation will depend, of course, on the particulars of the students, teachers and subject matters involved. What research and anecdotal evidence make clear is that there isn’t one ideal class size for all ages, abilities and subjects.