What does loving teachers have to do with foreign policy?

In the final moments of the third presidential debate, a somewhat exasperated moderator, Bob Schieffer, tried to regain control of a conversation that had veered wildly off topic. The original question was about China’s currency manipulation, but after some back-and-forth, Republican nominee Mitt Romney was once again explaining why, despite his love of teachers, he doesn’t think hiring more of them would help the economy.

“I think we all love teachers,” Schieffer interjected.

It wasn’t the only time the candidates strayed from foreign policy—the topic of the debate—to American classrooms. Earlier in the night, President Obama had steered a discussion about America’s role in the world to his education policies, saying “we didn’t have a lot of chance to talk about this in the last debate.”

It wasn’t the only time the candidates strayed from foreign policy—the topic of the debate—to American classrooms. Earlier in the night, President Obama had steered a discussion about America’s role in the world to his education policies, saying “we didn’t have a lot of chance to talk about this in the last debate.”

In fact, both Obama and Romney returned to education again and again in all three debates—often in response to questions that had little to do with the topic. The surge of interest in education in the final weeks of the campaign, including campaign ads that attack Romney’s views on class size and sidetracked answers during debates, follows months in which both candidates mostly ignored the subject. Education’s sudden popularity has to do mainly with Obama, who has pounced on it as a way to draw a contrast between himself and Romney on the most important issue in the campaign—the economy.

Shortly after Romney selected Paul Ryan as a running mate, the Democrats seized on Ryan’s budget proposal, which could lead to cuts in federal funding for schools, and began making a new argument about the Republican platform: Romney sees education as an expense, and Obama sees it as an investment. That’s the message Democrats have been pushing whenever possible. Obama and his surrogates, including former President Bill Clinton, have repeatedly brought up Obama’s support of early childhood programs, funding for K-12 schools, and college affordability.

Ed in the Election

Read more of our stories looking at how education is being discussed/debated in the election.

It’s a concern Obama’s team hopes will resonate with the middle class, young people and his base. “He’s playing to a historical strength of Democrats,” said Andra Gillespie, a professor of political science at Emory University who has also worked as a pollster and political consultant. “What better time to talk about education issues than when people are back in school … or sending a child to college?”

Obama and Romney don’t actually disagree as much about education as they do about some other issues, such as tax policy. Romney has praised U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan, raising speculation that he might even appoint him to his cabinet if elected. Both candidates support charter schools and pay-for-performance for teachers. When Romney put out his white paper on education policies in May, it drew little criticism from Democrats. The Obama campaign has essentially ignored Romney’s signature K-12 proposal, which could create a nationwide voucher system for low-income and special-needs students.

When it comes to education, the main difference between the two presidential candidates is Paul Ryan. The Ryan budget, which was presented to Congress in 2011 and which Romney said he would have signed, calls for a 20 percent cut to discretionary funding. Although the budget doesn’t specify how that decrease will be divvied up among departments, Obama has repeatedly claimed that Romney would cut education spending by a fifth, if not more. The Republicans contend that is not true.

The Democrats have bolstered their narrative of an austerity-focused Republican ticket using Romney’s repeated statements that hiring more teachers won’t help grow the economy and that decreasing class size shouldn’t be a priority. They’ve sought to draw a contrast between those views and the investments that Obama has already made in education while in office, such as increasing the number of low-income college students receiving Pell Grants. Obama also reformed the student loan program and held student loan interest rates down. These changes, Obama says, have made college more affordable and student debt less daunting.

“It’s a positive theme for the future they can emphasize, rather than an attacking theme,” said David Lublin, a professor at American University.

Obama’s education messaging has put Romney on the defensive. The Republican contender abruptly promised in the first presidential debate that he wouldn’t cut education spending at all. He went from backing Ryan’s plan to tighten Pell Grant eligibility, which would shrink the number of students who receive federal help, to saying he wants the program to grow.

Romney has also discussed the need to drive down college costs and has mentioned a merit aid program he started for top performers in Massachusetts that provided scholarships for those who opted to attend in-state public universities and colleges. (The program ended up hurting students more than it helped them.)

Both candidates are trying to woo not only middle class voters with these arguments, but young ones as well. Young voters were crucial to Obama’s 2008 victory. While the demographic still supports him, polls suggest they’re less likely to vote this time. “President Obama needs to shore up his base,” Gillespie said. “He wants to frame himself, unlike the Republicans, as a champion of students.”

Romney has tried to close the youth gap between himself and Obama by frequently assuring those in college that he’ll have jobs waiting for them when they graduate.

Even if the Democrats have found a Republican weakness to exploit, however, it may be too little, too late. “I don’t think it’s been made enough of a focus that it’s necessarily a crystallized issue for the election,” Lublin said, adding the Democrats should have “identified [Romney] as negative on this issue before he changed his mind back to center.”

In all likelihood, education won’t be the number-one issue for many voters on Election Day. But the Obama campaign is hoping that some of its pro-education messaging—helped along by the repeated talk of teachers and schools—will sink in.

This story also appeared on Slate on October 26, 2012.

With time running out, teachers push pro-Obama message in swing states

In the swing states of Ohio and Florida, it’s crunch time for teachers unions, which in the final days of the campaign are getting out the vote for President Obama in droves — even though they disapprove of some of his policies.

American Federation of Teachers President Randi Weingarten urges Cincinnati teachers to knock on doors and phone bank on President Obama’s behalf. (Photo by Sarah Butrymowicz)

“The arguments have been made,” American Federation of Teachers (AFT) President Randi Weingarten said as she mingled with fellow union members in Cincinnati last weekend and talked up the importance of the election. “This trip is about mobilizing and getting out the vote.”

Weingarten is urging members in both states to donate time to Obama’s reelection campaign by join canvassing and phone banking efforts. The AFT, along with the larger National Education Association (NEA), has organized pro-Obama events across the country for months. With just about two weeks to go until Election Day, Weingarten’s bus tours in Ohio and Florida are an attempt to rally teachers for a final push.

The traditionally strong relationship between teachers unions and Democrats has been strained in recent months. The tensions came to a head last month in Chicago, when union members went on strike, in part over tying teacher evaluations to student test scores. They went up against Obama’s former chief of staff, Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel. In some cases, unions are even supporting Republicans this election cycle.

Ed in the Election

Read more of our stories looking at how education is being discussed/debated in the election.

For the most part though, the unions are still throwing most of their money and manpower toward the Democrats, who have also supported policies they like—including a bill to hire nearly 300,000 more teachers, which was scuttled by Republicans in Congress. Weingarten and NEA President Dennis Van Roekel have portrayed Obama as someone who genuinely cares about education and Romney as someone who will gut the public system in favor of privatization.

Other teachers agree. “It could be a whole lot worse,” said Wellyn Collins, a retired teacher in Cincinnati, of Obama’s first term. “There are a lot of people that have a lot of enthusiasm for reelecting the President.”

Ohio is a hugely important swing state in the tight race between Obama and Republican candidate Mitt Romney. No president has won without the state’s 18 electoral votes since 1960.

“This election will be decided in O-H-I-O,” Weingarten said to a group of members just outside of Cincinnati on Friday. “Can we find it in ourselves to volunteer to knock on some doors? Can we find it in ourselves to volunteer to call some people?”

Both national teachers unions, which have a combined 4.5 million members nationwide, have requested that their members donate time to support union-endorsed candidates. Historically, teachers unions have been a large player in politics because of their deep coffers and thousands of members, who can be mobilized for get-out-the-vote efforts.

The American Federation of Teachers launched a multi-state bus tour this weekend, spending the first leg of their trip in the important battleground state of Ohio. (Photo by Sarah Butrymowicz)

This year, the Ohio Education Association (OEA), the state affiliate of the NEA, is asking its 124,000 members to spend an hour or two of time calling potential voters, knocking on doors or attending a rally. All 26 offices across the state have phone-banking stations set up.

The union also mails flyers to their members urging them to support all the candidates the OEA has endorsed – and not just at the polls. President Patricia Frost-Brooks says she counts on teachers talking about the election with friends and community members as informal, word-of-mouth campaigning. Frost-Brooks, for example, goes down her Christmas card list, sending out notes explaining why she’s supporting certain candidates.

But neither union mandates any political involvement, and there’s no guarantee all—or even most—of the unions’ members will contribute to the get-out-the-vote efforts.

In Cincinnati, the Ohio Federation of Teachers (OFT) hopes that at minimum, 1 percent of its members will volunteer for a one- to three-hour shift recruiting voters. The union currently has about 5 percent of its members in the area participating in the “Walk, Talk or Pay” program, but Cincinnati leader Tom Frank is hopeful that number will be closer to 10 percent by Election Day.

Yet some union members in the area not only refuse to give their time to Obama, they won’t vote for him either. “We have a very conservative [section] within our union,” Frank said. He said his goal is to convince this group not to vote for Romney, because, Frank says, the Republican candidate gives too much support to charters and private education.

Many of Frank’s most dedicated volunteers are retired teachers, who have more time to give. The OFT held a summer training session for retirees to prepare them to organize and motivate other volunteers.

Collins, who attended the training session, spends six days a week talking to would-be voters to explain why they should vote for Obama. She says the effort feels worthwhile when she’s able to convince someone to register who wasn’t planning on voting at all.

A native of Kentucky, which has been a reliable Republican stronghold in the last three presidential elections, Collins often misses home – except during election season. “It’s the one time I really am happy I’m an Ohioan,” she said.

This story also appeared on NBCNews.com.

Five times a finalist, Miami-Dade finally takes home Broad Prize

Miami-Dade County’s public school system–which U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan said is moving in the “absolute right direction,’’–won the 2012 Broad Prize for Urban Education on Tuesday during a ceremony at the Museum of Modern Art .

Miami-Dade district science teacher Eugenio Machado instructs Gabriel Marino, Stella Leone and Melanie Larson. (Photo by Al Diaz/Miami Herald)

The win followed five nominations for The Broad prize, which recognizes gains in student achievement in large urban districts. Duncan highlighted the district’s success in outperforming all other comparable Florida districts in 2011 reading, math, and science tests at all school levels. He also commended its use of student data, which he said is driving improvement in the nation’s fourth largest school district.

The district, led by Superintendent Alberto Carvalho, serves nearly 350,000 students, 90 percent of whom are black or Hispanic and 70 percent low-income. The Broad Prize winner receives $550,000 in college scholarship money for high school seniors.

While Miami-Dade has notable accomplishments—the district’s graduation rate, for instance, increased 5.6 percent in one year, to nearly 78 percent in 2011—the district has also had some struggles. In 2011, in a move contested by the United Teachers of Dade, Miami-Dade was the first district in the state to award merit pay to its teachers, a statewide requirement for all Florida districts by 2014.

The state of Florida has also mandated a complicated teacher evaluation system in which 50 percent of evaluations are based on a complex formula involving student test scores. The other 50 percent is left up to districts. In Miami-Dade, that half is currently based on one formal observation by an administrator, a method that has been criticized throughout the U.S.

In early 2012, a report by the National Council on Teacher Quality, a research group based in Washington D.C., said that the district was not doing enough to get rid of underperforming teachers. The group suggested that the district provide more feedback to teachers, consider college and licensing test scores when hiring teachers, and give principals more authority in hiring.

More coverage

Eli Broad, co-founder of The Eli and Edythe Broad Foundation, reminded the audience at the award ceremony that the prize is about progress, not victory. (Disclaimer: the Broad Foundation is among the many supporters of The Hechinger Report.)

“We didn’t fall behind overnight and we are not going to catch up overnight either,” Broad said. “Even the districts here today…acknowledge that they have a long road ahead of them.”

Last year, the Charlotte-Mecklenburg School District in North Carolina won after reducing the achievement gap in high-school reading between African-American and white students by 11 percentage points between 2007 and 2010. The district had closed nearly a dozen schools, mostly in majority black neighborhoods and sent layoff notices to more than 700 teachers.

In the year since winning the prize, Charlotte-Mecklenburg graduation rates have increased nearly two percent to 75 percent, but test scores have remained low at some of the poorest performing schools.

The three runners-up of this year’s Broad Prize will each receive $150,000 in scholarship money. Two of these districts, the Corona-Norco Unified School district in California and The School District of Palm Beach County, Fla., were first-time finalists. The Houston Independent School District won the inaugural year of the award in 2002.

Survey: Today’s teaching force is less experienced, more open to change

More inexperienced teachers are in today’s classrooms than ever before and they are more open than their veteran colleagues to performance-driven options for how they’re evaluated and paid, according to the results of a new survey conducted by the Boston-based nonprofit Teach Plus.

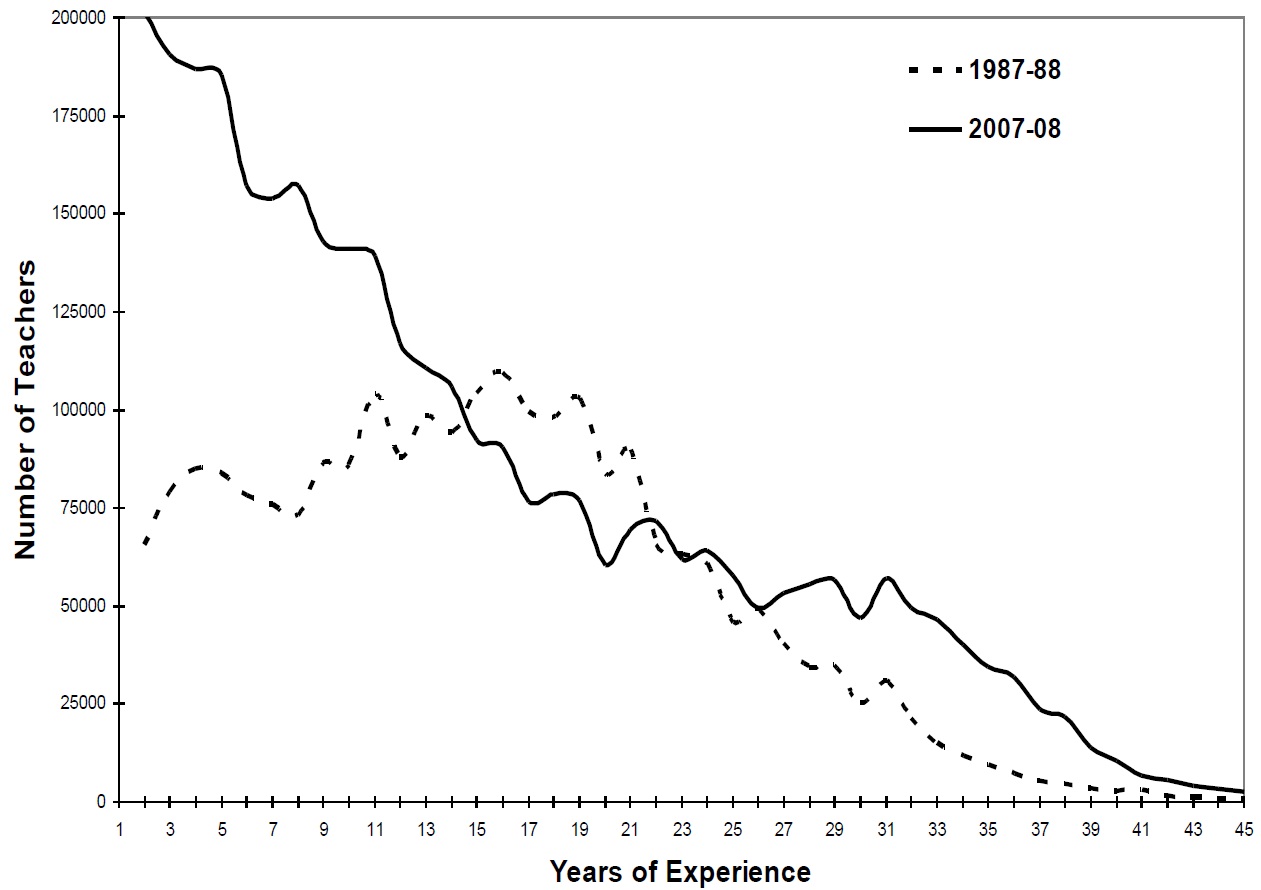

For the first time in decades, more than 50 percent of the nation’s teaching force is comprised of teachers who have been in the classroom under 10 years, Teach Plus found in “Great Expectations: Teachers’ Views on Elevating the Teaching Profession,” which looks at the changing demographics of U.S. teachers.

From “Seven Trends: The Transformation of the Teaching Force,” by Richard Ingersoll and Lisa Merrill (May 2012)

The national survey asked 1,015 new and veteran teachers their views on some of the most contentious issues in U.S. public education, like teacher evaluations and class size, to see if attitudes are shifting with an influx of newer teachers.

Despite differences in experience, teachers are generally united when it comes to working conditions. The majority of both newbies and veterans agree that class sizes should not be increased, even if doing so would provide districts with more funding to raising salaries. The two groups are also in agreement about keeping the school day shorter and said that increasing pay is key to elevating public respect for the profession.

On the topic of teacher evaluations, though—one of the most highly debated issues in education reform—the two demographics have mostly differing views. They agree that current teacher evaluations are ineffective at improving instruction, but 71 percent of less experienced teachers say their evaluation should be tied to student test score growth, compared to only 41 percent of veteran teachers.

Those who began teaching in the last decade are also more supportive of changing compensation and tenure systems, and more likely to think the use of student data is important to teach more effectively.

Celine Coggins, founder and CEO of Teach Plus, said a new generation of teachers has been exposed to the magnitude of the achievement gap, which may influence their attitudes and their belief in the importance of data.

Celine Coggins, founder and CEO of Teach Plus, said a new generation of teachers has been exposed to the magnitude of the achievement gap, which may influence their attitudes and their belief in the importance of data.

“Closing gaps among racial groups and across income levels motivates the commitment to teaching for so many,” Coggins said.

In 1987, the majority of teachers had 15 years of experience, according to a study by researchers at the University of Pennsylvania. Now, with about half of new teachers leaving urban classrooms within three years, teachers with just one year of experience are the most common in U.S. classrooms. And each year, 200,000 new teachers enter the profession, 65 percent of whom are recent college graduates.

Mark Teoh, director of research and knowledge at Teach Plus, said that these new teachers were most likely students during or after the introduction of the No Child Left Behind Act in 2002, and said their attitudes show they are more accustomed to testing and accountability than their more experienced colleagues.

At a time when states are introducing the Common Core standards and new evaluation methods, Teoh says these shifting teacher attitudes could influence education reform, as policymakers hear “what kind of profession these teachers want to see, and what kind of workforce they want to be a part of.”

The report also highlights problems that come with a younger, less experienced teaching force. Teach Plus recommends including teacher opinion in policymaking and encouraging newer teachers to take on leadership roles.

“There’s definitely room and a hunger for these teachers to be part in the policy process itself,” Teoh said. “They’re the ones who are there all the time, and they can provide the feedback, guidance and perspective that [are] needed.”

On the Campaign Trail: Clinton touts Obama’s higher education policies in Ohio

Former President Bill Clinton promised Thursday that if President Obama wins reelection, “nobody will ever have to drop out [of college] again because of the debt problem.” He was speaking at a rally featuring Bruce Springsteen in Ohio, in a major get-out-the vote effort in the swing state by the Obama campaign. Republican candidate Mitt Romney’s surrogates are also campaigning hard in the state, although they have focused more on jobs.

Romney supporters brave the rain for a “Commit to Mitt” bus tour stop in Steubenville, Ohio. (Photo by Sarah Butrymowicz)

Clinton made the same sweeping claim about Obama’s success in attacking college debt in his speech at the Democratic National Convention last month. His argument is based on Obama’s student loan reform policies. The former president detailed them again for the attendees at the rally in Parma, Ohio, telling them that they were the “most important thing that Congress and President Obama have done in the past four years that nearly nobody knows about.”

Obama’s student loan reform removed banks from the process so that students can now borrow money directly from the government. The Democrats have claimed this change saved $60 billion, which is now being applied to Pell grants for low-income students and tuition tax credits for families. Students now pay back their loan at a fixed percentage of their income.

Obama also signed a bill this summer that kept interest rates on student loans from doubling. It’s a measure that Republican nominee Mitt Romney said he also supported.

Christine Gregory, a financial aid consultant who works with colleges and universities, attended the Parma rally and praised the president’s effort to keep interest rates low and his focus on community colleges. “They can turn out graduates who are matched to what the employer is looking for,” Gregory said.

Clinton also hit that topic in his speech. He highlighted a community college in the area that had partnered with the Cleveland Clinic to train adults with no college degrees for new healthcare jobs. “We need to build a community college network in America,” Clinton said. “Barack Obama will do it. His opponent will not.”

In the months leading up to the election, Ohio, with its 18 electoral votes, has emerged as an increasingly important swing state. No one has won the presidency without winning Ohio since 1960.

As Clinton and Springsteen stumped for Obama, Ohio’s Lieutenant Governor Mary Taylor and Congressman Bill Johnson wound their way through rural Jefferson County, near the Pennsylvania border in eastern Ohio, on a “Commit to Mitt” bus tour. They encouraged people to take advantage of Ohio’s early voting option and to volunteer on Election Day.

Speaking to about two-dozen people who gathered in the rain in Steubenville, Ohio, the Taylor and Johnson focused their remarks on jobs and the economy. Several people in the crowd said they were unfamiliar with Romney’s education policies, but at least one person was a fan of the former Massachusetts governor’s promises to expand school choice.

“I’m in strong support of educational vouchers,” said Steubenville resident Randolph Knob, who came out to hear Taylor speak. “I think parents should have a choice.” He sent his seven children to Catholic schools.

Knob said he believed growing the economy would end up improving education; the more money people earn, the more taxes the government can collect to spend on public sector jobs like teaching, he said. It’s the “best thing that could happen to teachers,” he said.

In an interview, Johnson also spoke of the educational benefits of a strong economy. He told The Hechinger Report that a healthy one would bring down the cost of education

Parents choose new charter operator in first ever ‘parent trigger’

A small group of parents in Adelanto, Calif., became the first in the nation Thursday to choose a charter operator to take over their neighborhood school through the controversial “parent trigger” law.

On a 50 to 3 vote, parents who voted chose LaVerne Elementary Preparatory Academy as the charter operator to take over the embattled Desert Trails Elementary School, which has been at the center of a bitter battle for the past nine months.

On a 50 to 3 vote, parents who voted chose LaVerne Elementary Preparatory Academy as the charter operator to take over the embattled Desert Trails Elementary School, which has been at the center of a bitter battle for the past nine months.

California’s Parent Empowerment Act of 2010, known as the parent trigger law, enables parents representing more than 50 percent of students to sign a petition to force major reforms on a low-performing school, from firing the principal and half the staff to a charter conversion.

At Desert Trails, more than 600 students and 286 parents signed a petition last year seeking a charter conversion. Accounting for parents who had since left the school, 180 were eligible to vote. Parents who did not sign the petition were not eligible.

Some parents who fiercely oppose the conversion have vowed to pull their children out of the school next fall.

“I want nothing to do with the people behind it,” said parent Maggie Flamenco.

The choice was between LaVerne Elementary, which has run a K-8 charter school in Hesperia, Calif., since 2008 and focuses on a classical curriculum with an emphasis on Latin, and the Lewis Center for Educational Research, which runs a K-12 charter school in Apple Valley, Calif., with a focus on science and project-based learning.

More coverage

Doreen Diaz, the lead parent organizer for the conversion, said she preferred LaVerne Elementary because it has outperformed Desert Trails on test scores even though it has similar demographics. LaVerne Elementary scored a 911 on California’s 1,000-point Academic Performance Index last year, compared to Desert Trails’ score of a 699.

She also liked that LaVerne Elementary’s proposal included a more formalized structure for parent involvement. LaVerne Elementary promised to create a parent board comprised of parents, a staff member, the principal, assistant principal and other school representatives. The proposal stated that the parent board would serve as a liaison between school administration and parents.

“That’s a level of power the district has refused to give to parents,” said Gabe Rose, deputy director of Parent Revolution, the Los Angeles nonprofit bankrolling the parent union.

The parent union did not allow parents who hadn’t signed the petition to cast a ballot because they had already outlined the process in writing when they campaigned last winter, Rose said.

California regulations state that the petitioners should select and solicit the operator, he said.

“We’re bound by the promise we gave to the community about the process,” Rose said. “We would have loved to be able to open it up to more.”

The next step is for LaVerne Elementary to formally submit its charter proposal to the school district. Charter schools are independently run and publicly financed and overseen by an agency. In California, that agency is typically the local school district’s governing board. The Adelanto School District must approve the charter proposal if it deems it meets the state’s requirements, including a sound fiscal plan and appropriate curriculum. All current students at the school and their siblings would be guaranteed spots.

Parents first started organizing the Desert Trails Parent Union in June 2011, and the union first filed its petition to convert the school into a charter school on Jan. 12. Several battles with the district over verifying signatures ensued, and the parent union ultimately won a key victory in court last week.

In the meantime, momentum for parent trigger legislation throughout the nation has been building. Well-funded advocacy groups like Parent Revolution and StudentsFirst are now using the new movie “Won’t Back Down” to rally more support.

By the end of this winter, Parent Revolution anticipates that additional parent groups in the Los Angeles or greater California area will be going public with their own pushes to invoke parent trigger, Rose said.

Will Mississippi jump in and provide funds for early learning?

Advocates of a privately funded early education program in Mississippi are asking the state for five million dollars to expand, in a move they hope will improve school readiness for children who too often start behind – and stay behind.

From left, Ms. Rhonda Winston, Davion Sims (in her lap), MeKenzi Stephens, Eziyah Robinson, Kimiyah Nuttall, Kaitlyn White and Eben Banks Jr. at Little Angels Day Care, which is part of the Building Blocks program. (Photo by Kim Palmer)

The request to expand Mississippi Building Blocks follows increasing media coverage of early education in Mississippi, one of 11 states in the nation, and the only state in the south, that does not fund pre-K. The program works to improve school readiness for children in the state with the highest child poverty rate, and some of the lowest test scores in the nation.

Claiborne Barksdale, CEO of the Barksdale Reading Institute, which helps fund Building Blocks, said during a news conference earlier this week that money will run out before the fifth year if the state does not contribute. Former president and CEO of Netscape Communications, Jim Barksdale, told WLBT that this program is essential for Mississippi’s future. “These children are better prepared for kindergarten which means they’re better prepared to go on to school life ahead of them,” Barksdale said. “They’re better prepared to be contributing citizens of this state.”

Mississippi has more than 1700 child care centers in the state, but quality varies greatly. There are no consistent education standards, and early childhood teachers are not required to have more than a high school diploma or GED.

Mississippi Learning

The Hechinger Report is taking a long look at what’s behind the woeful performance of Mississippi’s schoolchildren, as well as possible solutions to help them catch up.

Building Blocks has helped over 500 early childhood programs teach literacy and school readiness skills.

The program provides equipment, a research-based curriculum, and teacher training in 31 Mississippi counties. A University of Missouri study found the program had a positive impact on children’s skills and social emotional development, and children in the program, when compared to a control group, had double the scores on school-readiness skills assessments. The program has also proved to be affordable— since its inception four years ago, it has been sustained entirely by private funding.

Mississippi’s Department of Education has already requested an unprecedented $2.5 million in the 2014 budget request for an early education pilot program, but Gov. Phil Bryant has not commented on whether Building Blocks will receive any of those funds.

The Hechinger Report, via partnerships in Time and NBC News, has highlighted problems resulting from the lack of high quality early childhood education in the state.

Ed in the Election: Obama, Romney pivot to education in second debate

There were no questions about education in the second presidential debate, held on Tuesday night, but both President Barack Obama and Republican candidate Mitt Romney brought it up often during a town hall meeting with undecided voters. Both men spoke largely in generalities about the need to improve the country’s schools and offered up their track records as proof they would be able to do so.

President Obama and Mitt Romney at the second presidential debate on Oct. 16. (Photo by Scout Tufankjian/Obama for America)

In the past month, the Obama campaign has sought to draw a distinction between Obama’s and Romney’s willingness to invest in education. Carrying on that effort, Obama in particular steered the conversation toward education multiple times, making links between gun violence and school performance, and student loans and workplace equality for women.

While answering a question about assault rifles, Obama emphasized the importance of improving the country’s schools, reiterating claims that his opponent doesn’t want to hire more teachers. “When Governor Romney was asked whether teachers, hiring more teachers, was important to growing our economy, Governor Romney said that doesn’t grow our economy,” Obama said before he was interrupted by moderator Candy Crowley of CNN.

“The question, Mr. President, was guns here,” she said. “I need us to move along.”

Romney was not given a chance to respond, but has said that hiring teachers won’t help the economy. He did, however, agree with Obama’s basic premise that there was a relationship between violence and education.

Romney boasted about his own education track record, mentioning twice during the debate that Massachusetts’ schools were ranked first in the country during his tenure as governor. “I was able also to get our schools ranked number one in the nation, so 100 percent of our kids would have a bright opportunity for a future,” Romney said.

The state did perform the highest on the country’s National Assessment of Educational Progress when Romney was in office, but has consistently topped the list for decades. The state also does well – if not the best – in other ratings.

Romney also mentioned the John and Abigail Adams Scholarship Program on his list of education achievements in the state. The scholarship awarded students who performed in the top 25 percent of their class on high school exams with a full-tuition scholarship to in-state public universities and colleges. Research suggests that this program, however, may actually be detrimental to students because it entices them to choose lower quality options where it takes them longer to complete their degrees.

Obama took time to tout his track record as well, mentioning that he’d worked with governors in 46 states to institute reforms – such as adoption of the Common Core State Standards and changes to teacher evaluation systems – and worked to make college more affordable.

“We’ve expanded Pell Grants for millions of people, including millions of young women, all across the country,” Obama said while answering a question about equality in the workplace. “We did it by taking $60 billion that was going to banks and lenders as middlemen for the student loan program, and we said, let’s just cut out the middle man. Let’s give the money directly to the student.”

Romney has said that he wants to reinstate private banks in the student-loan market. He used the debate to reiterate a recently articulated support for Pell Grants, which go to low-income students.

His running mate, Paul Ryan, has called for tightening eligibility requirements for the grants and leaving unchanged the maximum amount available. Earlier in the month, Romney said he thought the maximum should increase along with inflation, and he repeated the idea Tuesday. “I want to make sure we keep our Pell Grant program growing,” he said.

Why Mitt Romney’s Massachusetts education plan backfired

Ask Mitt Romney to name his signature education initiative as governor of Massachusetts and he’ll likely answer that it was the John and Abigail Adams Scholarship Program. The scholarship, established in 2004, covers tuition at in-state public colleges and universities for students who score in the top 25 percent of their district on the state’s 10th-grade math and English standardized tests.

“I got more hugs on Adams Scholarship day than I did at Christmas,” Romney said in a May speech about education. “And parents—more than once—told me that they had been worried they would not be able to afford college and that the scholarship would make a difference. Here in America, every child deserves a chance. It shouldn’t be reserved for the fortunate few.”

The cost of college is one of the major barriers for many poor students, so it seems logical that paying for their tuition would help more of them graduate from college. But research into the Adams Scholarship and the 12 others like it across the country suggests that these programs do little to improve college access because they typically go to students who already plan to attend college. If anything, these researchers say, the scholarships can widen existing income and racial gaps in college attendance.

A study released this summer by Harvard’s John F. Kennedy School of Government found that Massachusetts students were likely to use the scholarship to attend a state school with fewer resources than private schools they might have gone to otherwise. The result? Students who use the scholarship actually take longer to graduate.

“This is a very unusual example of a situation in which we make money available to students, and they actually end up worse off,” said report co-author Joshua Goodman, an assistant professor of public policy at the Kennedy School.

Merit aid programs emerged in the early 1990s as a well-intentioned, politically popular attempt to help more people go to college. Even as state budgets have been slashed, the majority of these scholarships have survived.

They typically have three goals: to provide extra incentive for students to work hard in high school; to keep the best and brightest students in-state, thereby avoiding a state brain drain; and to improve college enrollment rates. And it’s not clear they’re succeeding at any of the three.

There’s little evidence that the promise of financial aid boosts high-school achievement, Goodman said. While some states have had success in keeping their highest-performing students in state for college, that doesn’t mean they stay after earning a degree.

Massachusetts’ John and Abigail Adams Scholarship Program, started by Mitt Romney, provides incentive for students to go to state schools like the University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

And although there is some conflicting research on the topic, many of the studies that have been done on merit aid find that it does not have a large impact on college attendance, particularly for minority and low-income students.

Don Heller, dean of Michigan State University’s College of Education who has studied merit aid programs extensively, has found the money is more likely to flow to white or Asian students and those with a higher socioeconomic status.

Romney’s original proposal called for a scholarship program that would go to the top quartile of test takers statewide. After critics argued the plan would heavily favor middle- and high-income students, the scholarship was amended to be given out on a district-by-district basis. Even so, minority and low-income students have qualified at much lower rates than their peers.

The same is true in other states. In Michigan, for instance, 31 percent of all high-school seniors scored well enough on the state’s standardized exam to earn a merit scholarship, but just 7.1 percent of African-Americans met the threshold in 2000, prompting a lawsuit from civil rights groups. The scholarship was ultimately discontinued due to lack of funding in 2006.

“Most of the money goes to subsidize kids from upper-income, upper-middle-income [families] who would have been going to college anyway,” Heller said. “If the goal of states is to get more students to college, then merit scholarships are not very efficient.”

The main reason many of these programs fail to close access gaps, according to Goodman and Heller, is that the criteria used to determine scholarship eligibility—typically GPA and test scores—correlate with income.

Georgia’s HOPE scholarship program, one of the oldest and largest merit aid programs in the country, has doled out more than $6.6 billion to nearly 1.6 million students since 1993. To qualify, students must earn a 3.0 GPA in high school. If so, they get a free ride to an in-state public school. One study found, however, that 96 percent of students who used the HOPE scholarship were already planning to go to college.

At the same time, many of the students who meet the 3.0 high-school GPA criterion in Georgia are not prepared for college. About half of Georgia’s HOPE recipients lose their scholarships between freshman and sophomore year for failing to keep up the same GPA in college. (Most programs have a similar stipulation for scholarship renewal.) Only 30 percent keep the scholarship for all four years. Research has also found that HOPE students are more likely to withdraw from classes or take a lighter course load once in college.

And the Massachusetts scholarship isn’t as generous as it first sounds. Romney’s program covers tuition at $1,700 per year. But it does not cover fees, which can be several thousand dollars more in Massachusetts, or room and board. Goodman’s report found that students who earned the Adams Scholarship were likely to be swayed by the money despite the program’s relatively small impact on overall cost.

At Massachusetts’ Brockton High School, more the half of the 264 Adams Scholarship students eligible for the money in the class of 2012 decided to use it. Counselor Catherine Leger, noting that about 70 percent of her students are low-income, said that she promotes using the scholarship to help mitigate tuition costs.

But many students who decide to go to state schools, which often have limited funding, are turning down higher-quality options, Goodman found. The schools they end up attending have fewer resources, reflected in measures such as student-teacher ratios, and they have lower-quality advising, which means that students get less academic support and are more likely to be shut out of classes that become too full. “The student may not appreciate that those factors will affect their ability to complete degrees,” Goodman said.

So how should states help more students go to college? Goodman suggests spending funds that currently go to merit scholarships on improving state universities instead or creating new scholarship programs that factor in need as well as merit to provide a targeted incentive. The current programs were a well-intentioned idea, but it’s time to re-examine the data.

This story also appeared on Slate.com as part of an exclusive collaboration. Reproduction not allowed.

Ed in the Election: Obama and Romney advisors debate education spending

President Obama isn’t the big investor in education he has claimed to be on the campaign trail, Mitt Romney’s education advisor, Phil Handy, argued in a debate Monday with his Democratic counterpart. Obama advisor Jon Schnur countered that the math behind Romney’s budget plan virtually ensures there will be cuts to education if the former Massachusetts governor is elected.

Both Handy and Schnur used the debate to crystallize the differences between their respective candidate’s educational philosophies, which were sometimes blurred when Romney and Obama themselves debated earlier this month.

The debate was hosted by hosted by Teachers College, Columbia University, and sponsored by Education Week. (Disclaimer: The Hechinger Report is published by an independent institute based at Teachers College.)

Handy is a former chairman of Florida’s State Board of Education and a member of the Board of Directors at the Foundation for Excellence in Education, a nonprofit education reform group started by former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush. Schnur is the co-founder and former CEO of New Leaders, a group that trains principals, and current executive director of America Achieves, a nonprofit aiming to improve school systems.

Schnur said Obama would continue to put more resources toward education, repeating one of President Obama’s standard arguments that investing in education will improve the economy. But Handy attacked the notion that Obama’s spending on education, including the $4.3 billion Race to the Top program, has been an investment. He argued that the administration’s programs have focused on short-term funding solutions, which have run out or will soon do so. “You can’t put a lot more money into it on a short-term basis and call it an investment,” Handy said.

He also echoed Romney’s claim from the first presidential debate earlier this month that a Romney administration would avoid cutting education. He said it would be possible to reduce the country’s deficit by changing entitlement programs while leaving education spending alone. He added, however, that Romney would not increase funding for early education. (Obama has pushed for more than $500 million for an Early Learning Challenge Fund, which Congress passed this year.) “You just can’t keep adding to the deficit,” Handy said.

Schnur countered that the president has made long-term investments, too, including large increases for the Pell Grant program to help low-income students pay for college. He also pointed to Obama’s modest increases in education funding since being elected. And if Romney wants to keep promises he’s made to increase defense funding and Social Security protections while still reducing the deficit, Schnur argued, it’ll be impossible not to touch education. “The Romney campaign on education is imprisoned by the Romney budget policy,” he said. “There’s no way the math holds up.”

Schnur said significant reductions to discretionary programs would have an impact on other programs related to poverty and children—such as federally subsidized school breakfasts and lunches for low-income children. Schnur also attacked Romney’s school choice plan as “meaningless,” saying it would be impractical to run on a national level.

Handy criticized the No Child Left Behind waivers granted by the Obama administration, which have allowed states to avoid sanctions for not reaching the law’s target for universal proficiency by promising to enact other education reforms. He described the waivers as too prescriptive and said allowing states to set different standards for different ethnicities was “soft bigotry”—echoing a favorite phrase of George W. Bush’s, who often spoke of the “soft bigotry of low expectations” in U.S. public education.

Schnur defended the waivers by evoking a widespread criticism of the No Child Left Behind law: As accountability ratcheted up, research found that states lowered standards in order to meet targets. “What you’re saying falls into the traps of the worst parts of No Child Left Behind,” he said.

The two men also squared off over college costs. Schnur praised Obama’s move to reduce the amount students must pay on their college loans once they enter the workforce. The loans of students who make continuous payments would be forgiven after 20 years instead of 25. Handy warned that forgiving student debt could become a whole new entitlement program. And although he supports the Pell Grant program, he also repeated a frequent Republican argument that the grants are driving up the cost of tuition.

Both men described candidates who had made education a top priority in their public lives—Obama as a senator and during his first term as president, and Romney as governor of Massachusetts.

But Romney’s belief that the federal government should stay out of the way of state leadership in education is problematic to Schnur. “I might vote for Mitt Romney for governor,” he said. “But I don’t think that’s a basis for electing a president.”