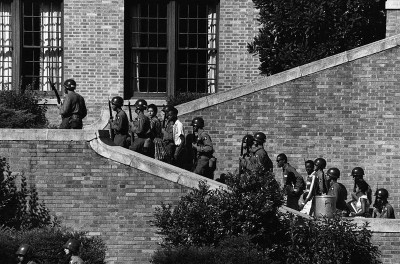

Soldiers from the 101st Airborne Division escort the Little Rock Nine students into the all-white Central High School in Little Rock, Ark. (1957)

A court decision last week blocking New York City’s efforts to shut down 19 failing schools may be the end of that fight, but more heated battles over whether to close schools are likely to crop up in New York and elsewhere in the coming months.

The federal government is now in the process of handing out “school improvement grants” to districts across the country in an effort to turn around failing schools, and one of the four options is to shut them down.

The New York case shows us that it’s unlikely these schools will go quietly. The fights over closings are likely to shape up in the way conflicts over schools usually do: with teachers’ unions on the side of saving schools, and reformers in the mold of NYC Schools Chancellor Joel Klein promoting closures as a way to make accountability real.

What was a little more surprising in the New York case was the third party in the picture, the NAACP, which joined the case on the side of the teachers’ union. Local leaders of the civil rights group said they were participating because African-American parents were complaining that the closures violated their children’s rights.

This is not the first time school closings have sparked anger in African-American communities. In the 1960s and ’70s, during another massive reform effort – school desegregation – hundreds of schools, most of them in black neighborhoods, were closed. Although African Americans overwhelmingly supported desegregation, the school closures didn’t go over well – even when the schools were housed in aging buildings and didn’t seem to serve students well. Closing schools in the black part of town was usually a tactic to soften white resistance to desegregation. That way, white students wouldn’t have to venture into black areas; instead, blacks took on much of the burdens of busing.

Just as infuriating to many blacks was the disregard for the history and importance of these schools in their communities. They were not just schools; they were centers where people gathered to socialize and attend cultural events. They were also reminders of the history that blacks had overcome to bring education to their children.

Many of the schools, particularly in the segregated South, were built and supported without much help from the government. The money often came from the meager wages of farmers and factory workers, as well as Northern philanthropists. Education historian Vanessa Siddle Walker has documented how caring for the well-being of students, not just their academic achievement, was a central mission of black schools. It was a mission that black parents valued, and one they feared would be lost if whites took over their children’s education. In one county in North Carolina, black parents refused to send their children to the newly desegregated white school for an entire year to protest the closure of their own school on the other side of town.

It’s not that black parents didn’t want quality schools for their children — quite the opposite. The protests were rooted in concerns that African-American children would fair worse in their new schools.

Although it turned out that black children tended to perform better academically in desegregated environments — the achievement gap was its smallest ever during the height of desegregation — African-American parents were often dismayed by continued inequalities, like ability-tracking that isolated black students from their white peers and higher rates of suspensions for black students.

In the end, closing black schools helped undermine support for desegregation among African Americans. Today, it’s a tactic that’s been all but abandoned.

Although current circumstances surrounding school closings are substantially different than what happened during desegregation – for one, New York never had a desegregation program – reformers pushing school closure might be wise to pay attention to past anger at closures. It’s also worth noting that several of the schools slated for closure in New York City were built just a few years ago to replace other failing schools.

New York City deputy mayor, Dennis Walcott, a former civil rights leader himself, told the New York Times back in February that it was “mind-boggling and incredible” that the NAACP would join “a lawsuit to keep persistently failing schools open.”

A quick look at history suggests it shouldn’t be so hard to believe.