One surefire way to get people’s attention is to say the exact opposite of what everyone else is saying — to claim that conventional wisdom is wrong.

And sometimes, of course, conventional wisdom is wrong. This was one of the themes of Freakonomics, the hugely popular book by Stephen Dubner and Steven Levitt that went on to become a New York Times blog and now a documentary.

Conventional wisdom once held that the world was flat. Oops. Conventional wisdom also once held that cigarettes weren’t carcinogenic. Wrong again.

In the field of education, the belief that poor students couldn’t learn was once prevalent, as Jay Mathews pointed out in a radio show I was on this week. Also in education, there’s been the occasional claim that we need fewer students, not more, going to and graduating from college. This was a central claim by Charles Murray in his recent book Real Education: Four Simple Truths for Bringing America’s Schools Back to Reality (2008). Murray says too many people are going to college, and that ultimately this is very detrimental to the U.S. economy. (Forget not that Murray himself is not just a college graduate — of Harvard, no less — but also the holder of a Ph.D. from MIT.)

Now we have the deputy editorial-page editor of Cleveland’s Plain Dealer, Kevin O’Brien, saying the same thing. In an op-ed entitled “Ohio is stuck on what ‘everybody knows,'” O’Brien writes that “everybody knows” we need more college graduates — and that “everybody knows” college graduates earn more than high school graduates, and that a more educated workforce would make Ohio a more attractive place for businesses.

Trouble is, he doesn’t buy any of it. What “everybody knows,” O’Brien says, is actually nonsense.

He concludes with the following flourish:

Ohio already has more college students, more college graduates, more college teachers, more college administrators, more college departments, more college majors, more college courses and more college campuses than it needs. The proof of that is found in the inability of many graduates to find jobs — especially the jobs for which they ostensibly have been prepared — in Ohio when they graduate.

What Ohio needs is a chainsaw just for red tape. What Ohio needs is a right-to-work law. What Ohio needs is energy whose cost isn’t artificially inflated by government-mandated green fantasies. What Ohio needs is the return of some good, old-fashioned, dirty industry — the kinds of jobs that employ kids who aren’t cut out for college.

You’re not going to hear those truths from people who run for office, though. Ohioans aren’t ready for them. Everybody knows that.

Hmm. I’m not convinced.

On one point, at least, O’Brien is plain wrong. He writes, “Everybody knows the stats on earnings potential for college graduates vs. high school graduates — the stats that don’t factor in the effect on earnings potential of starting one’s working life $60,000 in debt.”

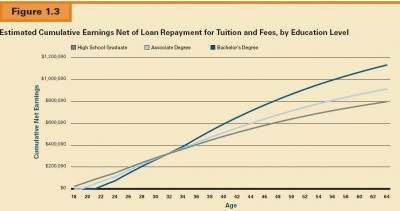

Actually, a recent College Board study called “Education Pays 2010: The Benefits of Higher Education for Individuals and Society” did precisely this calculation, taking into account both the fact that college graduates enter the workforce in debt and that they sit out of the workforce, on average, four years. The study’s conclusion? The break-even point is age 33, after which college graduates’ estimated lifetime earnings shoot past those who haven’t earned college degrees.

If average life expectancy in the U.S. were under 33 years, then, yes, O’Brien might be right on this point. But average life expectancy in this country is about 78 years. If we’re likely to spend much of our lives working — and most of us are, I’m afraid — then it seems inarguable that getting the education we need to do rewarding, well-compensated work is a sound investment. Conventional wisdom in this instance might well be right.