Can failure transform us in important — and healthy — ways? Should we champion failure as much as we do success? Is failure really just success by another name?

And in education, should we learn not just to live with but to love leaders who fail?

Such questions were at the heart of a recent BAM! Radio Network conversation in which I participated. The title of the talk was “When Leaders Flunk: The Critical Role of Failure to Success in Education,” and joining me in the discussion were Megan McArdle (of The Atlantic) and Holly Elissa Bruno (our host).

Earlier this year, McArdle wrote a piece in Time magazine — in a section called “10 Ideas for the Next 10 Years” — about the upsides of failure. She argued that “failure is one of the most economically important tools we have. The goal shouldn’t be to eliminate failure; it should be to build a system resilient enough to withstand it. … Yet instead of celebrating all our successes in building systems that fail well, we’ve become wedded to the fantasy of a system that doesn’t fail at all.”

Michael Jordan (photo by Steve Lipofsky, Basketballphoto.com)

McArdle was looking specifically at failure in the business world here, but our radio conversation addressed failure more broadly. Bruno began the discussion by quoting Michael Jordan, quite possibly the greatest basketball player in NBA history, who has said: “I’ve missed more than 9,000 shots in my career. I’ve lost almost 300 games. Twenty-six times, I’ve been trusted to take the game winning shot and missed. I’ve failed over and over and over again in my life. And that is why I succeed.”

This is a vital message for everyone to hear, especially children — who are often crushed when they fall short, perhaps because so many young people in the U.S. grow up hearing nothing but how amazing and unique they are. (Psychology professor Jean Twenge wrote an entire book, called Generation Me: Why Today’s Young Americans Are More Confident, Assertive, Entitled–and More Miserable Than Ever Before, on the pitfalls of the self-esteem movement.)

In reality, each of us probably isn’t that amazing or unique, no matter what our parents might say. Neither is anyone perfect. Failure is everywhere. (I remember meeting failure firsthand in fifth grade when report cards were distributed. I went home and bragged to Mom that I’d gotten all As. Her lightning-quick response, having just glanced at my report card? “No, you didn’t. Look here: see, there’s an A-.” Ouch. That was the last time I ever bragged about grades.)

If failure is ubiquitous, the question becomes how can we deal with it in productive ways? And should we as a society make a conscious effort to reduce failure’s stigma? Might it sometimes make sense to promote, rather than to shun, failure?

These are tough questions without clear answers.

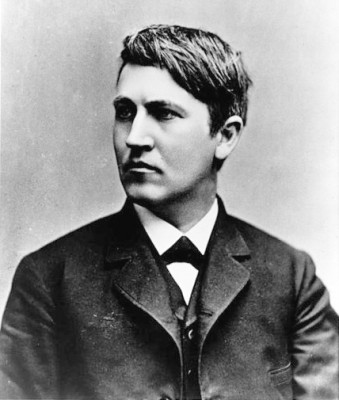

Thomas Edison, in 1878

McArdle pointed to the example of Thomas Edison, who needed nearly 10,000 tries to come up with a filament for the incandescent light bulb that would last more than a few hours. Some saw his thousands of attempts as wasted effort, but Edison saw them in a completely different light (pardon the pun!): he discovered 9,999 things that didn’t work as good filaments, which was useful knowledge in itself. By knowing what didn’t work, Edison was eventually able to find what did.

My favorite example of the relative definitions of failure and success comes from baseball. Ted Williams is the last major-league player to have hit over .400 in a single season, which he did in 1941. Nearly seven decades have come and gone but no one’s improved on his mark. That’s how hard it is to hit the ball. In fact, the very best major-league players typically “fail” at the plate twice as often as they succeed. But we’ve defined success in the major leagues as getting a hit roughly one out of every three at bats — which is very reassuring to me. Success, we must remember, is not a synonym for perfection.

On the subject of education, the question arose as to whether leaders should have the freedom to experiment and possibly fail. McArdle argued “yes,” and pointed out that we need to model failure for kids. They need to see adults learning to cope with uncertainty, risk and failure — and I couldn’t agree more.

But I’m somewhat wary of experimentation for experimentation’s sake, especially when those being experimented upon are real people — and, in the case of schools, children whose very lives can be dramatically affected (for better or worse) by our experiments. In this regard, I suggested we have an ethical obligation to be prudent — not too risky and not too reckless — in our educational experiments because they can have lifelong implications for students.

I also believe that failure at the individual level is a lot less harmful than failure at the institutional level – because a lot less is at stake. Leaders who fail don’t go down in flames alone; they typically take entire organizations with them.

Educational leaders should, of course, be willing to try new things and take the occasional, well-calculated risk. But they’d be wise to make decisions grounded in reliable research, not just based on passing fads. One reason urban school superintendents tend not to last very long in their jobs — the average tenure is about three years — is because they’re hired by people who want to seek quick and radical change, which usually means trying lots of new (and fairly risky) things. As Rick Hess has documented, the result is often akin to the spinning wheels of a vehicle stuck in mud: lots of (apparent) action that ultimately leads nowhere. That is, urban superintendents too frequently overpromise and under-deliver, in part because they’re almost required to overpromise in job interviews.

So, what’s your take on failure? Should we encourage more of it? Or should we, at the very least, seek to reduce the stigma associated with it?