What if schools didn’t have to work alone to improve student achievement? That was the question we asked in a recent article about the miserable state of public education in Camden, N.J., one of the poorest cities in the country. Now, a study out today by Education Sector, a Washington, D.C.-based education policy think tank, delves further into the question of whether public schools should share responsibility for improving the academic outcomes of impoverished children.

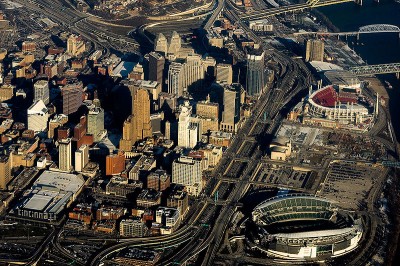

In Cincinnati, schools and other agencies are sharing responsibility for student results (Photo courtesy of Kevin Hartnell under a Creative Commons License)

The argument is that non-school agencies—after-school organizations, public housing departments, local colleges and universities—should also be held accountable for student success. The report’s authors—Kelly Bathgate, Richard Lee Colvin and Elena Silva—note that this is far from a simple idea to execute, however: “Some critics fear that broadening accountability for academic results beyond the schools will weaken promising school reforms. And they are right that if everyone is accountable for results, then, in fact, no one is.”

In Cincinnati, the focus of the report, a coalition of agencies tried to avoid this problem by making a list of goals for each organization involved that fit with its specific mission. In the case of a mentoring organization, the report says, goals might have included “improving the mentees’ attendance, reducing the number of times they get in trouble, and following them to track whether they are graduating from high school and enrolling in college.”

But the experiment’s outcomes so far are mixed.

“Over the past four years, the communities showed progress on 40 community indicators. More students are demonstrating proficiency in math and reading and enrolling in college. One particularly bright spot is that the percentage of children who come to kindergarten ready to learn has risen substantially,” the report’s authors write.

“But,” they go on to say, “there is a long way to go. The percentage of students graduating from Cincinnati Public Schools who enroll in college within two years of high school graduation was 65 percent in 2009, an increase since 2005, but a 4 percentage point drop from the previous year.”

The project in Cincinnati may have implications for the future of the Obama administration’s Promise Neighborhoods initiative, which was meant to replicate the Harlem Children Zone’s model around the country. For more details about the Cincinnati project and its results thus far, see the full Education Sector report, “Striving for Student Success: A Model of Shared Accountability.”