Graduation rates at U.S. high schools have hovered around 70 percent for decades. But many urban and rural areas routinely graduate only 40 or 50 percent of their students. The dropout crisis in many cities is acute, with 2,000 high schools producing half of the nation’s dropouts. Cutting the dropout rate and turning around “dropout factories” are among the Obama administration’s priorities. But what strategies work? Earlier this summer, The Hechinger Report — in collaboration with the Washington Monthly — looked at how New York City, Philadelphia and Portland, Ore., have fared in their attempts to cut dropout rates.

Now, two new reports from Jobs for the Future (JFF) look at dropout prevention policies in all 50 states as well as what can be done for students who’ve already dropped out. Nationally, experts estimate that about 1.2 million students drop out each year, a figure so large it’s hard to wrap one’s head around it. Consider this: roughly 1.2 million students attend the public schools of New York City and Washington, D.C. — so imagine if all of those students quit in the same year. That is how big our country’s dropout problem is.

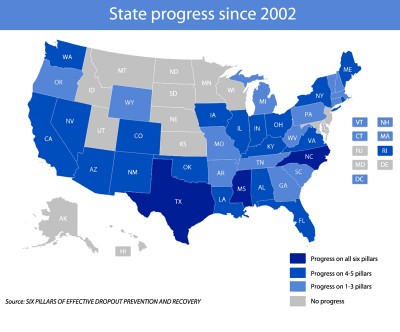

One of the JFF reports, “Six Pillars of Effective Dropout Prevention and Recovery: An Assessment of Current State Policy and How to Improve It,” looks at which states are doing which things JFF believes are critical to prevent dropouts and to get those who have dropped out back on track. The six pillars are:

1. Reinforce the right to a public education

2. Count and account for dropouts

3. Use graduation and on-track rates to trigger significant and transformative reform

4. Invent new models

5. Accelerate preparation for postsecondary success

6. Provide stable funding for systemic reform

On some of these fronts, many states have made progress in recent years. JFF identifies, for instance, 31 states that have taken action to reinforce the right to public education — by, among other things, raising the compulsory age of attendance to 18 or by stating that students have a right to a secondary education through age 21 or beyond. (States that don’t articulate such a right for their students, the report notes, have in the past given “explicit leeway to schools and districts to turn away older returning dropouts seeking a diploma if the district or school determines that they cannot ‘reasonably graduate’ by their 20th or 21st birthday due to age or lack or credits.” A footnote in the JFF report says that these states include Alabama, Florida, Illinois, Kansas, Rhode Island, Utah and Vermont.)

On other fronts, there has been little to no progress. Only 15 states have programs that “accelerate preparation for postsecondary success,” by which JFF means one or more of the following four options: dual enrollment, Advanced Placement, credit recovery and online learning. And just seven states have policies in place that foster the creation of new models for dropout prevention and recovery.

The other JFF report, “Reinventing Alternative Education: An Assessment of Current State Policy and How to Improve It,” spells out seven steps states could take to strengthen alternative-education options:

1. Broaden eligibility

2. Clarify state and district roles and responsibilities

3. Strengthen accountability for results

4. Increase support for innovation

5. Ensure high-quality staff

6. Enhance student support services

7. Enrich funding

Once again, many states appear to do some of these things relatively well already. Thirty-two states have taken steps to broaden eligibility guidelines, with the ideal intent of bringing “alternative education into the mainstream as a legitimate pathway toward obtaining high school and postsecondary credentials.” But not a single state presently has a policy in place to ensure high-quality staff in alternative-education programs.

Clearly, there is much room for improvement. The U.S.’s dropout problem will remain high on the agenda of politicians and policymakers across the country because the growing consensus is that a bachelor’s degree is the new high school diploma. Few people seem to believe that a middle-class lifestyle is realistic anymore in the U.S. without some kind of postsecondary training.