A quarter-century ago, the nation was transfixed by the question, Where’s the beef?

Now, the question we should be asking ourselves about our nation’s schools is, Where’s the rigor?

Or, Where’s the academic beef?

Concerns about the lack of rigor in U.S. schools were renewed yesterday, when new data were published on how prepared — or not — U.S. high school students are for college. Writing in the Wall Street Journal, Stephanie Banchero said, “New data show that fewer than 25% of 2010 graduates who took the ACT college-entrance exam possessed the academic skills necessary to pass entry-level [college] courses.”

The story, as reported by many outlets, was that the average ACT score has fallen slightly since 2007. But the real story — and the one that Banchero focused on — is that the vast majority of our high school graduates aren’t ready for college or a career. And this holds true even when they follow a supposedly “rigorous” course of study, taking four years of English and three years each of math, science and social studies.

It turns out that much of what U.S. schools now offer is “rigorous” in name only. Said differently, a distinct lack of academic rigor is de rigueur.

Banchero quotes Susan Traiman, public policy director for the Business Roundtable, as calling the disconnect between the ACT results and supposedly rigorous coursework “false advertising” by high schools.

Part of the problem with talk about “rigor” is that no one really seems to agree on what the word means. Governors boast of the rigors of their K-12 educational systems, while every principal proclaims his or her school “rigorous.” The Common Core Standards, meanwhile, “include rigorous content and application of knowledge through high-order skills.”

A lack of clarity on just what “academic rigor” is led us, with support from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, to explore the concept two years ago. We asked dozens of people — from politicians and policymakers to parents, students and teachers — to define the concept for us. We asked leading neuroscientists to explain what goes on in the brain when someone engages in rigorous learning. We looked at curricula that claim to be rigorous and asked whether they truly are. We also looked at what other countries do to offer their students a more rigorous education than the one most U.S. students receive. We invite you to explore our findings here.

It’s now the year 2010, but our schools often feel stuck where they were in the 1980s.

Where’s the progress?

Scores on the National Assessment of Educational Progress, also referred to as the “Nation’s Report Card,” have been largely flat for the last few decades. High school graduates who head off to higher education turn out to be unready for the rigors of college much of the time. Alarming numbers of students need remediation, which is a nice way of saying they didn’t learn things in their K-12 careers that they could or should have. (Note that I’m not assigning blame here to specific groups — teachers, parents, students, administrators, politicians — but rather pointing out that our system in many ways isn’t working. We’re all culpable, to varying degrees, for the failure.)

I invite everyone to read, or reread, the National Commission on Excellence in Education’s report, A Nation At Risk: The Imperative For Educational Reform. Here’s an excerpt: “More and more young people emerge from high school ready neither for college nor for work. This predicament becomes more acute as the knowledge base continues its rapid expansion, the number of traditional jobs shrinks, and new jobs demand greater sophistication and preparation.”

How well these two sentences capture our predicament in 2010!

That they were originally written in 1983 should scare us. The diagnosis of America’s educational woes in A Nation At Risk is as relevant today as it was when first published nearly three decades ago. The report quotes Paul Copperman as saying, “Each generation of Americans has outstripped its parents in education, in literacy, and in economic attainment. For the first time in the history of our country, the educational skills of one generation will not surpass, will not equal, will not even approach, those of their parents.”

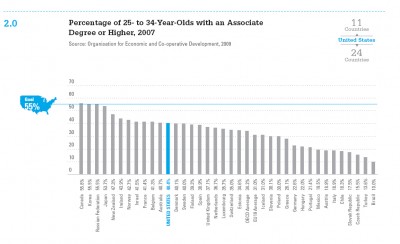

If this was true of those coming of age in the 1980s and 1990s — Generation X — it’s even truer of today’s young people. The alarm bells have been repeatedly sounded by the Obama administration, which has articulated a goal of having the U.S. reclaim first place in the world for the percentage of our population aged 25-34 with postsecondary degrees or certificates by the year 2020.

Where do we stand now? In 12th place.

Where did we stand in 1991? In third place.

In the 1970s, we’re rumored to have been number one.

Asking too little of our students does them a great disservice — something that even President George W. Bush acknowledged, saying that we as a nation must move beyond the “soft bigotry of low expectations,” the status quo in education that has prevailed for far too long.

A version of this article appeared on The Washington Post’s “Answer Sheet” on August 20, 2010.