Picking a major isn’t easy for many college students. For some, the decision is an important step toward realizing a lifelong dream; for others, it’s nothing but stress and uncertainty until the deadline to declare arrives, and then the tiniest of factors might tip the scales in favor of one concentration over others.

We all know that a student’s major heavily influences what courses he or she takes, but less well-known is how a student’s major also shapes the types of work done within, and beyond, these courses. A new report released by the National Survey of Student Engagement today, “Major Differences: Examining Student Engagement by Field of Study – Annual Results 2010,” reveals just how many differences there can be from major to major outside of the curriculum.

The survey, completed by 362,000 first-year students and seniors at 564 colleges across the country, yielded some “promising” and some “disappointing” findings, according to the report.

Among the positive findings were the facts that “three out of four seniors in nursing and physical education did service-learning as part of their coursework, well above the overall average of 49 percent” and that students majoring in most subjects “used quantitative information in their courses in several ways.”

There was also some unsurprising news — that English majors write more papers than their peers and that biology majors are more likely to do research with faculty than other students.

But despite all the focus on majors in this report, when it comes to the disappointing news, students’ specializations didn’t receive much focus.

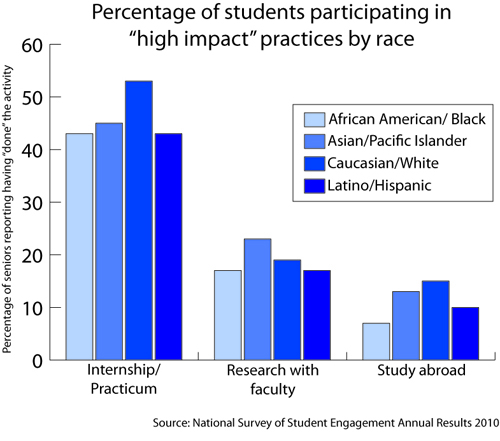

Across all majors, African-American and Latino students were less likely to study abroad, do research with faculty or have internships than their white and Asian peers. And, although not highlighted in the report, this year’s survey also showed that first-generation college students were also less likely to do these things.

Ensuring equal access to college has long been a goal in higher education, but this report joins other data that demonstrate something Estela Mara Bensimon at the Center for Urban Education has called “nuanced inequalities” between white and minority students, such as taking on leadership roles, studying abroad and making it on the dean’s list.

“One of the most critical challenges facing institutions of higher education in the twenty-first century is the need to be more accountable for producing equitable educational outcomes for students of color,” Bensimon wrote in an article in Liberal Education. “Although access to higher education has increased significantly over the past two decades, it has not translated into equitable educational outcomes.”