The Obama campaign has recently begun highlighting the differences between his education agenda and that of Mitt Romney. Will these new talking points be a theme at the Republican and Democratic nominating conventions? The Hechinger Report will be on the ground in Tampa and Charlotte to find out.

President Barack Obama delivers remarks on higher education and the economy at the University of Texas in Austin, Texas August 9, 2010. (Official White House Photo by Pete Souza)

Up until last week, education was rarely addressed on the campaign trail. But the stakes for the future of the U.S. education system are high in this election: The Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA), which funds and delineates the federal government’s role in the nation’s schools, will most likely be reauthorized in the next four years.

The last revision of the bill, President George W. Bush’s No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB), has been heavily criticized for its reliance on standardized tests and seemingly unattainable standard of universal proficiency by 2014. President Obama would ease up on some of the law’s restrictions, but maintain a robust federal role in local schools. Romney would move to reduce the government’s investment and involvement in education.

President Obama and Romney do share some common ground in their education platforms; both support charter schools, for example, and merit pay for the country’s best teachers. They both also speak of our failing schools and the pressing need to prepare American students for global competition. But the paths they would take to do this differ in important ways.

The Obama administration has largely used a carrot-and-stick approach to changing the education system. Over the past six months, the Department of Education has granted waivers from NCLB penalties to 26 states in return for promises that they will introduce other education reforms and accountability measures.

Under Obama’s Race to the Top initiative, a competition in which states promised a series of changes to their education systems in return for federal money, an unprecedented number of states are overhauling how teachers are evaluated, paid and let go.

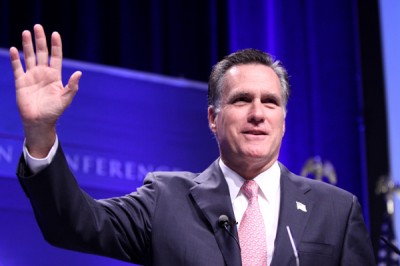

Some Republicans have criticized Obama’s education initiatives as overreaching by the federal government. Although Romney would not eliminate the Department of Education – as President Ronald Reagan once sought to do – he would consolidate the agency with another or “perhaps make it a heck of a lot smaller,” he told donors in April.

Under a Romney administration, school choice would be a priority. The Obama administration has thrown its support behind charter schools – awarding some points in Race to the Top for states that raise caps on the number of charters. Romney, though, wants to see a school choice system that includes vouchers for private schools in addition to more charters. Romney’s white paper on education calls for low-income and special-needs students to be able to go to any school, public or private, of their choice, using funds from the federal government.

Romney’s support of private sector involvement in education extends into higher education. He wants to allow private bank involvement in student loans (Obama eliminated their role in March of 2010). He has also praised for-profit, private colleges and campaigned on their campuses. Romney argues that for-profit schools increase competition in the post-secondary landscape and can help keep the cost of college down.

The Obama administration is one of many critics of for-profits, arguing that they leave graduates with large loans and few employment opportunities. Under Obama, the Department of Education developed regulations that will pull federal financial aid from schools where graduates are unable to find “gainful employment.” Romney would repeal this.

Due to Tropical Storm Isaac, the Republican National Committee Convention is off to a slow start; all speeches for the evening have been postponed until later in the week. Starting tomorrow, check in with The Hechinger Report this week and next for analysis of speeches, coverage of off-the-floor convention events and exclusive interviews with national education leaders.