Turnover Among New Teachers (source: Richard Ingersoll)

NPR’s Claudio Sanchez had an interesting story on Thursday about the Boston Teacher Residency (BTR) program, which seeks to provide would-be teachers with the kind of intensive field preparation that would-be doctors receive during medical school rounds.

The former superintendent of the Boston Public Schools, Tom Payzant, founded the program in 2003. Seventy-five “residents” go through the program each year, many later filling hard-to-staff positions (special ed, science, math) in Boston public schools. Payzant likens his program to boot-camp.

Listening to the story, I was struck by the similarities between the Boston Teacher Residency program and the more traditional teacher-education program that I completed the same year BTR began. Both place future teachers in Boston public schools for “residencies,” both entail extensive student-teaching under the guidance of mentors, both require taking full graduate-school courseloads and both end in a master’s degree. My program, at Harvard, also had a distinct boot-camp feel to it.

Maybe my teacher-ed program is unusual in how it prepares future teachers, or maybe the BTR isn’t actually all that revolutionary or different from many teacher-ed programs. I suspect the latter.

Payzant certainly seems to think the BTR is up to something most ed schools aren’t: “Most teacher training institutions focus more on content and less on practice and how people teach,” Payzant says in the NPR story. But I wonder whether this sweeping statement is really true. It’s a common claim — one that Secretary of Education Arne Duncan likes to make, too — but I question its empirical basis. Duncan cites a 2006 study of ed schools by Arthur Levine, a former president of Teachers College, but his choice of quotations from Levine’s study makes a rather different point. Levine summarized his study thus: “The bottom line is that we lack empirical evidence of what works in preparing teachers for an outcome-based education system. We don’t know what, where, how, or when teacher education is most effective.”

So how much truth is there to Payzant and Duncan’s claims that most teacher-ed programs focus on content at the expense of practice? I’d say the current evidence is mostly ancedotal; as Levine points out, we don’t know much. And there are, no doubt, also things about teacher-ed programs that we don’t even know we don’t know.

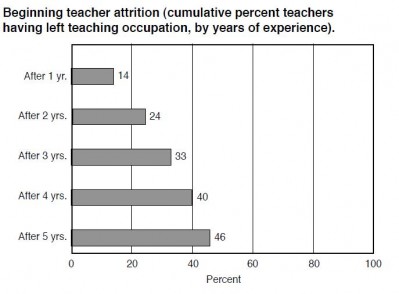

Near the end of the NPR story, the reporter quotes the BTR’s program director, Jesse Solomon, saying his program is superior to most because its graduates don’t quit teaching as quickly as the graduates of other teacher-ed programs. (Nationally, it’s estimated that a third of new teachers quit the profession after just three years, and nearly half quit by the fifth year, according to the research of professor Richard Ingersoll.)

But the program director’s evidence is shaky. According to Sanchez, the NPR reporter, “85 percent of BTR’s graduates stay in the classroom much longer” than two or three years. Hmm. I wonder how “much longer” is being defined here. Given that BTR only began in 2003 — and thus its first residents didn’t graduate until 2004 — we should remember we’re only a few years removed from when they began their teaching careers. Thus, if the program’s first graduates remain in the classroom, they’re still only in their sixth year of teaching. Does that constitute staying in the classroom “much longer” than those who leave after 2-3 years?

The point is that Solomon’s claim has little empirical basis because BTR only dates back to 2003. (Therefore, half of the program’s graduates have yet to complete their third year of teaching.)

Simply put, not enough time has elapsed to determine whether retention rates differ significantly between BTR graduates and graduates of more traditional teacher-ed programs. It should also be noted that BTR graduates have an extra incentive not to quit right away: they are required to teach in the Boston Public Schools for three years after graduation. Quitters must retroactively foot the program’s tuition bill ($10,000).

Such residency programs likely have merit, but more and better research is needed before we declare them radically different from and superior to the more traditional teacher-ed programs out there.