Affirmative action in college admissions is on the Supreme Court docket again this year after a white student named Abigail Fisher challenged a University of Texas program meant to promote diversity on UT campuses.

Affirmative-action proponents, including many university leaders, are concerned that if the University of Texas loses, efforts to increase diversity in U.S. colleges will be severely undercut. Critics of affirmative action are thrilled that the issue is back in play after a 2003 Supreme Court decision in a lawsuit against the University of Michigan seemed to settle the issue, allowing colleges and universities leeway to consider a student’s race as one of many factors in admissions decisions.

Minority enrollment in higher education has been on the rise, according to a 2010 Pew Research Center study, with Hispanic enrollment increasing the fastest. Whites made up 62 percent of the freshman class at four-year institutions in 2008, the report found, down from 83 percent in 1976. (That’s about the same as the percentage of whites in the larger population, although the percentage of minorities among young people is higher.) Nevertheless, the percentages of black and Hispanic young people enrolled in higher education are still lower than those of whites and Asians.

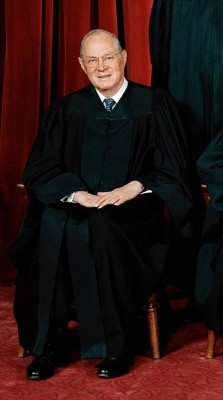

Which way the Supreme Court goes on this case will most likely rest with Justice Anthony Kennedy, the swing vote on the court, who has been a vociferous critic of racial quotas, but who has also published some fairly nuanced opinions on race in college admissions. Because Justice Elena Kagan has recused herself from the case, there will only be eight justices voting.

If Kennedy votes with the conservative wing of the court, the Texas program could be overturned, meaning many colleges and universities—both public and private—may have to overhaul how they make admissions decisions. If he joins the three remaining liberals, resulting in a tie, the lower-court decision—which upheld the Texas program—would stand. Or, he could come down somewhere in the middle, joining the conservatives or liberals, but writing a separate opinion that will hold more weight due to his swing-vote status.

That’s what happened in the last case involving race and schools in 2007, and lawyers for both sides will no doubt be poring over Kennedy’s past opinions as they plan oral arguments meant to sway him. Here’s a quick summary of what they will find:

In a 1992 decision in a desegregation case out of Georgia, Freeman v. Pitts, Kennedy had the following to say about whether K-12 schools should strive for racial balance in student populations:

“In one sense of the term,” he wrote, “vestiges of past segregation by state decree do remain in our society and in our schools. Past wrongs to the black race, wrongs committed by the State and in its name, are a stubborn fact of history. And stubborn facts of history linger and persist.” But, “racial balance is not to be achieved for its own sake,” he concluded.

In the 2003 University of Michigan case, Grutter v. Bollinger, although he sided with the conservatives who wanted to strike down the school’s use of race in admissions, Kennedy wrote a separate opinion, distancing himself from their more hard-line views. A racial quota, he wrote, “can be the most divisive of all policies, containing within it the potential to destroy confidence in the Constitution and in the idea of equality.” Yet race might play a role as a “modest factor among many others.”

Finally, in his opinion in desegregation cases out of Louisville and Seattle in 2007, he came down in the middle on the question of whether the districts’ use of race to assign K-12 students was permissible under the U.S. Constitution.

“That the school districts consider these plans to be necessary should remind us that our highest aspirations are yet unfulfilled,” he wrote. “But the solutions mandated by these school districts must themselves be lawful. To make race matter now so that it might not matter later may entrench the very prejudices we seek to overcome.”

He added, however, that “diversity, depending on its meaning and definition, is a compelling educational goal a school district may pursue,” and criticized the opinion of Chief Justice John Roberts, saying it implied “an all-too-unyielding insistence that race cannot be a factor in instances when, in my view, it may be taken into account.”

At the University of Texas, officials insist—and the lower courts have agreed—that race was just one factor among many that were used to admit a small pool of students (under 10 percent). We’ll see if their program is one of the instances of schools using race in admissions that Kennedy deems permissible.

This post also appeared on the College Inc. blog of The Washington Post on February 23, 2012. Reproduction of this story is not allowed.