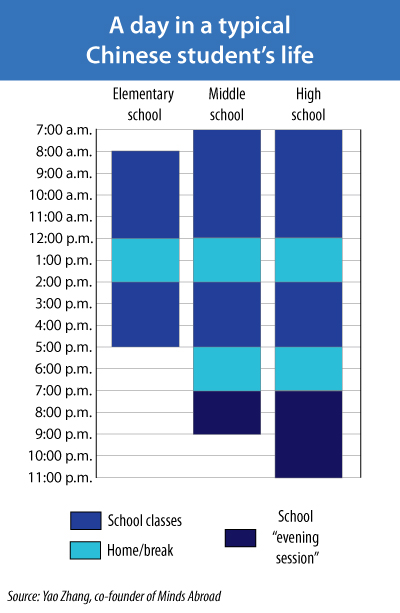

When bemoaning the United States’ comparatively low test scores on international assessments, some are quick to point to one factor that sets Chinese students apart from their American peers: the length of the school day. Unlike in America, where the length of the school day general stays constant from first grade through high school (if not shortening in the final year or two of school), the Chinese public school year grows as students get older. And the competition also increases, said Yao Zhang, a Chinese native who co-founded Minds Abroad, a company that coordinates study-abroad opportunities in rural China. Zhang is completing her Ph.D. in Economics and Education at Columbia University. She recently walked The Hechinger Report through a day in the life of Chinese students at public elementary, middle and high schools.

Elementary school starts at age seven for students in China. In the country’s mega-cities, like Beijing and Shanghai, where transportation is a large factor, students will go to school from 8 am to 3 pm with only a short break for lunch. But in most areas around the country, there’s a break from school for lunch and, often, a lunch-time nap at home. In primary school, students learn Chinese, math, geography and the basics of the natural sciences. English starts in third grade. There are also music, painting and physical-education classes, and one class that translates to “education of thoughts and morality,” Zhang said. This class covers a bit of political science and history, with stories about Chinese heroes.

By middle school, the competitive pressure to get into any high school—not just the top ones—is palpable. Admission is determined almost exclusively by performance on a single test, and only about 70 percent of students who finish middle school go on to high school. Even in primary school, parents start investing money in math Olympiads or musical-instrument training for children whose test-scores might make them borderline candidates for acceptance; extraordinary talent in math or music could be just enough to make the difference. Moving to different neighborhoods to get into better schools is a common strategy, as are hiring private tutors and making $1,000 “donations” to magnet-like middle schools.

And the workload ratchets up in middle school, too. Students spend from 7 am to 8 am at school reading, either in English or Chinese, and reciting to teachers. School ends at 5 pm, but the dinner break is shortened for an hour of “play time”—or physical fitness—beginning at 6 pm. After that, students stay at school for “evening sessions,” which function like study halls or tutoring periods. Students do homework and study, while teachers assist them. Physics, chemistry, biology and political science are tacked on to the elementary school course-load, as well as electives like calligraphy and computer science.

With under 30 percent of high-school graduates getting into college—based entirely on how students do on a “one-shot, one-kill test,” as Zhang put it—most students spend almost all waking hours studying. The subject areas of high-school courses don’t differ much from those in middle school, though phys-ed typically ends after 10th grade. Evening sessions at the high-school level conclude at 11 pm. And, for the many students who attend public boarding schools far from their hometowns, most of their lunch and dinner breaks are spent hitting the books. “Lack of sleep is very common for Chinese high-school students,” Zhang said.