Fourth- and eighth-graders’ scores showed modest improvement and racial achievement gaps narrowed on the 2011 National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), commonly known as the “Nation’s Report Card,” which was released Tuesday. The gap between disadvantaged students and their more affluent peers remained largely unchanged, however, and widened in fourth-grade reading.

Compared to 2009, this year’s NAEP scores rose by one point in fourth- and eighth-grade math and eighth-grade reading, but stayed flat in fourth-grade reading. Since 1992, the year NAEP began, math scores have risen substantially, but reading scores have seen only minimal gains.

The black-white score gap closed by one point in both fourth- and eighth-grade math, and the Hispanic-white gap narrowed by one point in fourth-grade math and four points in eighth-grade math. In fourth-grade reading, however, the black-white gap widened.

Perhaps most interesting, there were gains in both reading and math across all income levels, even as the number of people living at or below the poverty line has grown and income gaps widened.

This year’s math results are the highest ever in both fourth and eighth grade. There were also gains in reading, especially among students who receive free- or reduced-price lunch, the indicator used by NAEP to identify poverty status.

Overall, both students living in poverty and more affluent students saw score increases in fourth-grade reading, but six states — Oregon, Washington, West Virginia, Vermont, New Hampshire, Maine — and the District of Columbia saw the income gap widen.

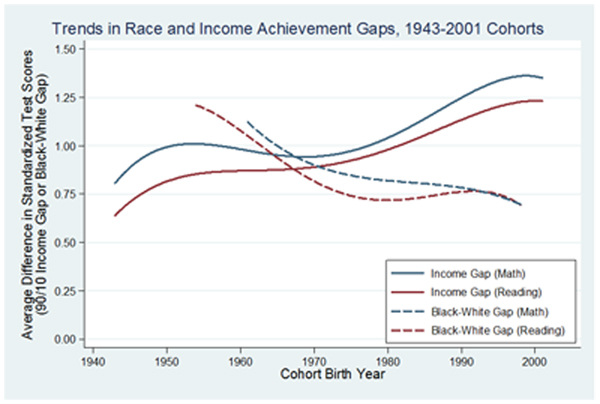

Race and Income Achievement Gap Trends (Courtesy of Sean Reardon; based on analysis reported in "Whither opportunity? Rising Inequality, Schools, and Children's Life Chances")

Sean Reardon, a professor and researcher at the Stanford University School of Education who studies the income achievement gap, says that the widening of the gap in these states could be due to a number of factors, including increased segregation, differences in teacher quality at poor and affluent schools, and varying No Child Left Behind requirements by state. He is currently conducting research to examine how state policy and demographic shifts may influence the income gap.

Reardon also said NAEP’s data on poverty may not be completely reliable because it is self-reported by students and leaves out many other factors.

“It won’t be a complete story,” Reardon said. “Because NAEP doesn’t do a good job of providing detail on income.”

While modest gains were seen in many areas, this year’s results pale in comparison to the gains made in the 1990s, a cause for worry according to U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan.

“The modest increases in NAEP scores are reason for concern as much as optimism,” Duncan said in a statement. “It’s clear that achievement is not accelerating fast enough for our nation’s children to compete in the knowledge economy of the 21st Century.”