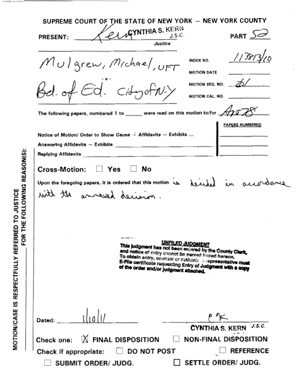

On Monday, January 10th, Justice Cynthia Kern ruled that the decision by the NYC Department of Education to publicly release Teacher Data Reports (TDRs) with individual teachers’ names attached was not “arbitrary and capricious.” That the chips fell this way isn’t terribly surprising.

Kern’s ruling is interesting more for what it doesn’t say than for what it does. And the United Federation of Teachers (UFT) has already appealed, so her ruling almost certainly won’t be the final word on this subject. As I wrote last month, “regardless of what Judge Cynthia Kern decides, it’s safe to say that the current teacher-evaluation system is broken in most school districts nationwide — and that value-added analysis is here to stay.”

Among the highlights of what Kern did say:

• “This court is not passing judgment on the wisdom of the decision of the DOE, whether from a policy perspective or from any perspective, or whether the DOE had discretion under the law to make a different decision, nor is this court making any determination as to the value, accuracy or reliability of the TDRs.”

• “The UFT’s argument that the data reflected in the TDRs should not be released because the TDRs are so flawed and unreliable as to be subjective is without merit. The Court of Appeals has clearly held that there is no requirement that data be reliable for it to be disclosed. … Therefore, the unredacted TDRs may be released regardless of whether and to what extent they may be unreliable or otherwise flawed.”

• “Finally, the UFT’s argument that the DOE assured teachers that the TDRs were confidential means that they cannot be disclosed under FOIL is without merit. … regardless of whether Mr. Cerf’s letter constituted a binding agreement, ‘as a matter of public policy, the Board of Education cannot bargain away the public’s right to access to public records.’ … Accordingly, the DOE’s assurances that the TDRs would remain confidential cannot shield them from disclosure.”

What Kern didn’t say is that the court is essentially providing political cover for the NYC Department of Education to make a controversial decision — the final result of which is that, to many observes at least, the court will end up looking like the bad guy instead of the DOE.

But Kern’s ruling isn’t an endorsement of the DOE’s decision, as she makes clear in the first excerpt above: “This court is not passing judgment on the wisdom of the decision of the DOE.” The DOE could have decided otherwise — not to release the TDRs with teachers’ names attached — and then a very different lawsuit likely would have followed: media outlets, rather than the union, would probably have been the plaintiffs taking the DOE to court.

That lawsuit, however, never happened because the DOE decided — without being ordered to do so by any court — that it had no choice but to comply with the Freedom of Information Law request filed by various media organizations. Joel Klein explained the DOE’s rationale in a letter to city principals last October: “As it is the City’s legal interpretation that we are legally obligated to provide the media this information, it is our intent to provide the data as requested.” But it’s important to be clear here that this was an internal decision made by the DOE, not an action taken in response to a court order.

It’s also worth recalling Cathie Black’s position on whether the TDRs should be released with teachers’ names attached, which she articulated to the editorial board of the New York Daily News in December: “If it has to be released [under the law], we’re going to have to release it. … [but] Unless we are forced to do it now, we would not be releasing the data. We won’t be releasing the data.” Daily News reporter Joshua Greenman charitably characterized Black’s position on the to-release-or-not-to-release question “not black and white.”

All of this to say that the DOE has repeatedly maintained its actions are required by law, even though no court has issued an order to that effect. Whether a court would rule that the TDRs (with teachers’ names attached) must be publicly released remains in doubt; it’s a question that Justice Kern wasn’t considering, as she says in her decision.

For perspective on this case, I spoke with Professor Michael Rebell of Teachers College and Columbia Law School. Rebell — who was co-counsel for the plaintiffs in Campaign for Fiscal Equity vs. the State of New York (2003), a case that resulted in a planned $5.6-billion infusion of funds into NYC schools — told me that “the court’s ruling was outrageous. … One could certainly argue that this [ruling itself] was arbitrary and capricious.”

Rebell clarified that the “arbitrary and capricious” standard on which Kern was deciding the case gives a lot of discretion to judges. “A different judge might have ruled a different way, and an appeals court might rule another way,” Rebell said. If he were the judge, Rebell told me, he “would have gone the other way.”

Rebell explained his thinking this way: “The underlying facts are … that value-added has a lot of promise as an approach, but at this point it is not perfected enough that you can fairly identify teachers and say that this teacher is good or that teacher isn’t.”

What’s next? The UFT has appealed Kern’s decision, and the DOE has agreed to await the outcome of the appeal before taking any action. This means, Rebell pointed out, that it’s actually in the union’s interest for the appeal to take a long time because there’s no fear of teachers’ individual TDRs being released in the interim — that is, if the DOE sticks to its word.